Tocqueville: A Thinker for Uncertain Times

Portrait of Alexis de Tocqueville by Théodore Chassériau, 1850.

By Françoise Mélonio, biographer of Alexis de Tocqueville

First published in 1835, Alexis de Tocqueville’s Democracy in America became an instant classic in the U.S.—but in his native France, the author was met with suspicion. Branded “Tocqueville the American,” he wrote a bestselling book that was praised and doubted in equal measure. Historian Françoise Mélonio, whose new biography Tocqueville was published in France in September 2025, argues that his vision of democracy, rooted in civic participation and shared responsibility, remains vital today for both the U.S. and France.

STATES Who was Tocqueville when he left for America in 1831, and what were his motivations for going there?

FRANÇOISE MÉLONIO In my biography, I want the reader to be able to understand this multifaceted politician and thinker and emphasize that a person’s ideas are inseparable from the events of their life. Tocqueville’s trip to America can be explained first and foremost by his family background. Tocqueville was the great-grandson of Malesherbes, a major Enlightenment figure and a magistrate of the noblesse de robe (nobles of the robe), French aristocrats whose rank came from holding judicial or administrative posts. Malesherbes was a defender of the people against the tax-hungry monarchy, and he was director of the Librairie (the royal administration responsible for regulating and censoring printed works). He championed Diderot’s Encyclopédie even though he was tasked with policing its publication. When his own subordinates threatened to seize the proofs for it, he went so far as to move them to his own home. Malesherbes defended Louis XVI before the National Convention and was guillotined in 1794 as a result. He was a constant role model in Tocqueville’s life as a liberal, independent thinker.

On his mother’s side, Tocqueville’s family had a history of intellectual brilliance, but they were deeply scarred by revolution. After both Malesherbes and an uncle were guillotined, Tocqueville’s parents narrowly escaped execution thanks to the fall of Robespierre. All this fueled his persistent dread of revolutions, which would be rekindled in France in 1830 and 1848. It was this trauma that drove him to pursue a nonrevolutionary model of democratic (and republican) society—one that could strike a balance between freedom and order.

Tocqueville was a judicial magistrate, like his ancestor Malesherbes, when he set off in 1831 at age twenty-six. Entry-level magistrates were unpaid at the time, meaning they invariably came from wealthy backgrounds. After the July Revolution of 1830, Tocqueville no longer saw a future in the judiciary, so he turned to politics and found a solution in the form of a trip to America. He planned to examine the country and its relatively stable democracy and return with an understanding that would benefit France. This trip was an urgent quest to find answers that would be of use to his home country.

Why America rather than England, given its proximity and the high esteem it enjoyed among liberals?

The choice may seem surprising. In 1830, if young French liberals weren’t focused on England, they looked to Germany because of the strength of the Prussian model in the nineteenth century. Tocqueville, however, was convinced that the world of the aristocracy was a thing of the past. He no longer believed aristocracy and democracy were compatible, which François Guizot had maintained under the Restoration and the July Monarchy. With a certain aristocratic schadenfreude, he also thought the dominance of the bourgeoisie would not last.

America was, for him, a laboratory. He wanted to see what a democratic society looked like, a country that had reached maturity without revolution. That’s not to say he idealized the United States. Early on, he identified different regions and ideas of America, rejecting both the West—which he saw as too wild, too new—and the pro-slavery South, deeming it incompatible with European values. What he did observe and embrace was the peaceful, organized, civic-minded culture of the American Northeast, which he believed could serve as an example for France and Europe.

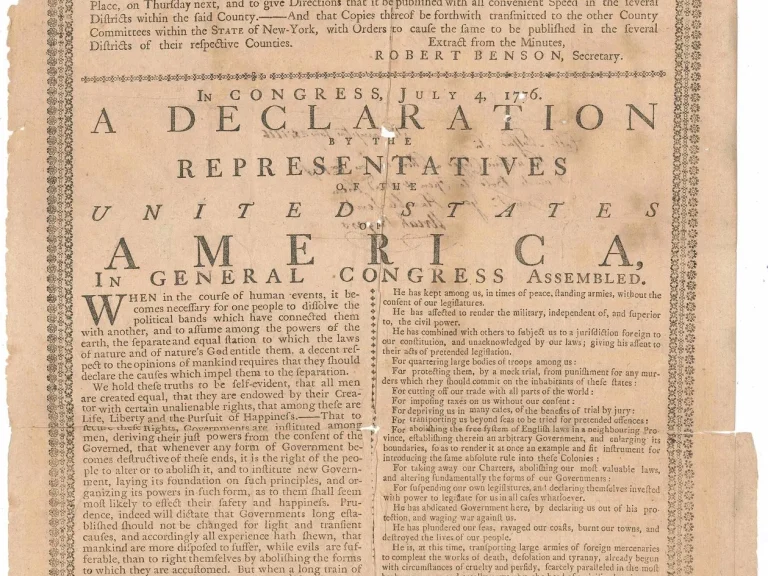

Your book tells the story of his memorable experience on Independence Day in 1831.

It was a revelation. At the beginning of his trip, Tocqueville was filled with doubts regarding the virtues of education, the potential of a great republic, the viability of the American model, and so forth. He initially saw New York as a mere bustling crowd of people obsessed with material success. But at a July 4 parade in Albany, New York, he discovered something else— what he thought of as the civic soul of America.

It was a simple, even modest spectacle: a band with a handful of flutes marching among assorted costumes—nothing like the solemn parades he was accustomed to as the son of an official back in France. However, he sensed in it a genuine patriotism and collective understanding. Where France remained divided over its revolutionary roots, the Americans embraced a common pride in their origins.

What type of society did he find in America?

He was struck by his discovery of an entrepreneurial society. In New York, he observed American dynamism and taste for risk (which he had the misfortune of experiencing firsthand when he was aboard a steamboat during an accident). What he admired was the unspoken motto, “I will try.” When his English was still quite poor, early on in his trip, he met with Francophiles and French-speaking contacts in Boston. This was where he discovered the vibrancy of community life and philanthropy, of which civic involvement was a key driver.

He also observed a certain equal dignity for all. At a reception, he spotted a statesman conversing with an executioner, which would have been unthinkable in France. The people he met explained that this equality was partly a façade, but the apparent absence of social discrimination left a profound impression.

Wasn’t this idea of equality rather naive?

Absolutely. In France, a person’s social rank was immediately evident from their attire and speech. Tocqueville speaks of the “rich races” and “poor races.” And at the political level, inequality was staggering: barely 200,000 voters in a population of 35 million. This contrast made his American experience more striking, even if he may have idealized it.

He would later earn the nickname “Tocqueville the American.” What was the attitude behind this sarcastic moniker?

It reflects a certain ambivalence. For Protestants, it was a compliment, and for others a sign of mistrust. France resented his assertion at the time—toward the end of Democracy in America—that the century was ruled by two great emerging powers: America and its power of freedom and Russia and its ability to compel obedience. Napoleon III took great exception to such a negation of France’s influence.

This was compounded by moral rejection, as American slavery and the Native American plight stirred France’s sympathy for the oppressed and its mistrust of the United States. The label of “American” therefore conveyed both an interest in Tocqueville and a critical distance from him.

What was Tocqueville’s stance on slavery and colonization?

He seldom mentions slavery in Democracy in America, but his travel journals shed more light on his views. His fellow traveler Gustave de Beaumont published a novel focusing solely on the subject, as though the two had decided to split their subject between them. Since Tocqueville was writing for a European readership, slavery obviously couldn’t be upheld as an example of the glories of American democracy.

But that doesn’t mean he was indifferent to the issue—far from it, in fact. Upon returning to France, he became involved with the French Society for the Abolition of Slavery, joined two committees, and drafted reports pleading for immediate abolition in the West Indies. He viewed the situation as less complex than that of the United States, where black and white societies were closely intertwined. According to him, the limited presence of Europeans in the West Indies allowed for more rapid emancipation there. He also asked that colonists be compensated for their slaves, not out of compassion, but arguing that all French society had benefited from slavery and that slave owners should not be saddled with the full costs of abolition. It was also a way to avoid economic collapse and ensure the survival of the emancipated. This position, although shocking today, was shared by many reformers of his time.

In Algeria, however, he adopted a resolutely colonialist position that clashed with his liberalism in other areas. Although he decried the “unfortunate necessities” of the conquest (massacres and brutality) and defended the rights of colonists and Arabs alike, he saw colonization as inevitable if France’s power were to rival that of England. This was imperialism born out of a fear of decline.

How was Democracy in America received?

The first volume was published in 1835. The publisher did not have high hopes for it and only printed five hundred copies, but it quickly became a bestseller, with translations into English, Swedish, and German. It was read by intellectuals all over Europe, from Metternich to Proudhon to Étienne Cabet, reverberating across the political spectrum, from monarchists to socialists. The second volume, published in 1840, was less successful. More abstract, it proposed a general theory of democratic societies based on the American example, but it lacked the exotic color and anecdotes of the first volume. The readership found it somewhat confusing.

What is the legacy of the book?

In France, Tocqueville remained influential until the 1870s, particularly because of his opposition to Napoleon III and the debates surrounding decentralization. He then fell into obscurity. Only his historical research into the Old Regime and the Revolution, for instance, was quoted by the leader of the socialist party Jean Jaurès. It wasn’t until the post-war period that he was rediscovered, first by Raymond Aron, then in the anti-totalitarian writings of Claude Lefort. His thinking about freedom had a new political and philosophical relevance because of the prominence of Soviet dissidents and concerns about the French Republic.

He never experienced such a period of obscurity in the United States, where George Wilson Pierson’s major study, Tocqueville and Beaumont in America (1938), established a lasting tradition of scholarly interest. Tocqueville’s own Democracy in America is a classic and is often quoted in public debates, usually prefaced by the question, “What would Tocqueville say about…”

He is often read as a prophet of modern democracy. Your biography seeks to put him back into the context of his own century.

His thinking was enlightened by his era. This became fully evident with the publishing of his correspondence in 2021. Tocqueville didn’t predict the future; he wrote about change in his own time. The strength of his work is its lucidity and his deep capacity for self-analysis. It is significant to note that the second volume, largely ignored upon its release, is today considered his seminal work. Americans interpret it, sometimes with surprising results, as a description of their own individualism, whereas Tocqueville was thinking primarily about France and Europe when writing it.

You quote this line from him: “When I entered life, aristocracy was dead and democracy as yet unborn.” What does this mean?

Tocqueville recognized he was aristocratic by inclination but democratic in his thinking. This distinction is a tenuous one: he believed an elite was necessary but should be elected rather than inherited. In his own life, he practiced what might be considered a form of democracy, marrying a commoner (who was older than him), sitting in the Chamber among the bourgeoisie, and remaining close to the people he represented in parliament. He embodied a constructive tension between aristocratic heritage and democratic ideals.

In the U.S., he also discovered the essential role of justice in democratic life.

He was particularly interested in the system of citizen juries, which he thought functioned as a “school of democracy.” For him, this was one of the major guarantees of freedom. He admired the absence of administrative justice. In the United States, even the state itself could be judged by ordinary courts. This was not the case in France, where the Conseil d’État, the highest administrative court, combined the roles of judge and jury—an embodiment of centralized power Tocqueville found deeply troubling.

Nevertheless, he was concerned by the fact that judges were elected and therefore dependent on popular opinion. He argued for a competent, stable, independent judiciary as an imperative condition of liberal justice.

Tocqueville also focused on individualism, often a source of misunderstanding between France and the United States.

In America, he observed how the enterprising individual was celebrated and that this was rarely in tension with the common good. But in France, when the word individualisme (individualism) entered use in the 1820s, it carried the negative connotation of withdrawal from society. Tocqueville turned it into one of the defining characteristics of a democratic society.

It was during his election campaign in Normandy that he noticed the electorate’s indifference toward the common interest: everyone took care of their own affairs. This observation informed the lengthy chapter on individualism in the volume published in 1840. Ironically, this reflection has become a core idea in contemporary American thought, as Robert Putnam has shown in his book Bowling Alone.

The nineteenth century was a time of revolution, which Tocqueville feared. What was his analysis?

In 1840, he wrote that revolution would become rare because it interrupts commerce. Yet, he witnessed the return of social upheaval toward the end of the decade. The more egalitarian a society becomes, the more everyone aspires to full equality. And in the face of immovable power, such tension leads to revolt. He attributed the French revolutions to this incapacity for reform through consensus. France is still a country where the government decides without much involvement from the people, which is why upheaval keeps repeating itself.

You describe Tocqueville as a thinker for uncertain times. Why should we still read him today?

He helps us think through moments of democratic uncertainty. In the United States, everything he took for granted—bicameralism, a free press, independence of the judiciary—is being eroded today, with religion sometimes fanning division. In France, other dangers are looming: the personalization of power inherited from the monarchy and the crisis of collective deliberation. Tocqueville reminds us that democracy cannot be reduced to just voting; he calls for discussion, education, and shared responsibility. His reflections on participation and deliberation are remarkably relevant today.

Interview by Raphaël Bourgois

Translated by Fast Forword

Françoise Mélonio is professor emeritus of Sorbonne University. She is the editor of Gallimard’s critical edition of Tocqueville’s complete works, which was published in English by University of Chicago Press. Her biography of Tocqueville was published in France in September 2025.

This interview first appeared in States, the annual magazine of Villa Albertine, published in January 2026.

Related content

Democracy in Two Worlds: A History of the Franco-American Alliance

Lafayette on Both Sides of the Atlantic

Sister Republics: Two Visions of Liberty

The Declaration of Independence: A Global Legacy

The Empty Throne: From Kings to Presidents

Archipelagoes of Art: A Transatlantic Museum Dialogue

My American Lessons

Who Shapes the Avant-Garde Now?

Big Theory: How America Brought French Theory to the World

Reel Love: A Story Starring French and American Cinema

Portfolio: Transatlantic Dreams

Between Fascination and Rivalry: 250 Years of Cultural Exchange