Lafayette on Both Sides of the Atlantic

Illustration by Bérénice Milon

By Vincent Bouat-Ferlier, director of the Chambrun Foundation

Lafayette is celebrated as the “Hero of Two Worlds,” yet his legacy reveals enduring tensions between French and American democracy. Vincent Bouat-Ferlier, director of the Chambrun Foundation, which works to preserve Lafayette’s legacy, examines how Lafayette’s fight for freedom, his defense of civil liberties, and his opposition to slavery were understood in his own time in both countries, and how those contrasting receptions reflect productive differences in the two nations’ political ideals.

In 1777, a nineteen-year-old man, born into an ancient noble family and heir to an immense fortune, stowed away in the port of Rochefort to cross the Atlantic. His name was Gilbert du Motier, Marquis de Lafayette. At this point in his life, he had neither military prestige nor a political career. But he harbored a deep conviction: the American colonists’ fight against the British monarchy was a fight for freedom, and it was his responsibility to play his part. This act, often described in mythic terms, deserves to be placed within a broader history—the political and cultural exchanges between Europe and America at the end of the eighteenth century.

Lafayette, who quickly became one of George Washington’s valued officers, embodied the idea of a bridge between two revolutions. Celebrated as the “Hero of Two Worlds,” he has always been an ambiguous figure: in America he is the faithful friend, the liberator, the living embodiment of the Franco-American alliance; in France he is a more controversial figure, both adored and spurned, seen as someone who oscillated between republican liberalism and loyalty to the constitutional monarchy. His trajectory, from the War of Independence to the French Revolution and then the July Revolution of 1830, illustrates the persistent tensions and differences between two models of democracy.

Studying Lafayette today means examining the shared ideological roots of France and the U.S., but also the lasting divergences in their relationships to state and government, their conceptions of freedom, and the role of commemorations. Above all, it means scrutinizing their differences: far from uniting the two countries in an illusory harmony, Lafayette symbolizes a relationship made up of mutual attractions and misunderstandings, convergences and rejections.

THE ATLANTIC REVOLUTIONS: FRATERNITY AND DIVERGENCE

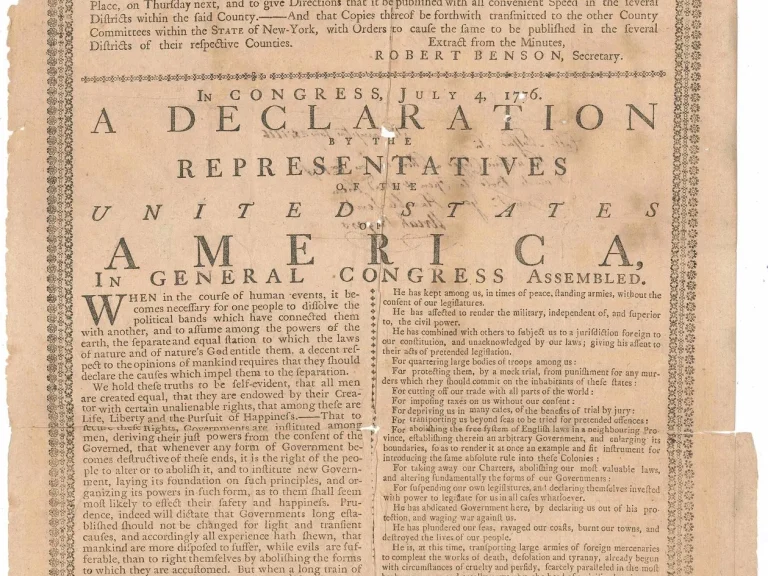

The American Revolution and the French Revolution are often presented as two founding moments in the same global story. On both sides of the Atlantic, intellectuals invoked natural rights, popular sovereignty, and the need to topple tyrannies and overcome injustice. The founding texts, the Declaration of Independence of 1776 and the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen of 1789, share a common language. But behind the words lurked major differences.

In the U.S., the revolutionary project aimed essentially to assert the autonomy of the colonies and win freedom from the distant power of the British Crown. The priority was to protect individual liberties against an excessively centralized government. Hence the emphasis on significant checks and balances: the separation of powers, the role of Congress, and the importance of the judiciary. In France, conversely, the Revolution attacked the entire ancien régime: its privileges and social hierarchies, the Church and the monarchy. The new political order was based on a strong, centralized state, guaranteeing equality and the unity of the nation.

Lafayette, as a participant in both revolutions, embodied this ambiguity. In America, he fought at Brandywine, played a part in the victory at Yorktown, and grew so close to Washington that he was viewed as the latter’s “adopted son.” Back in France, he became commander-in-chief of the National Guard in 1789; he proposed a draft Declaration of the Rights of Man inspired by the American model and drafted it with Jefferson’s help. But he quickly came up against revolutionary radicalization: his moderate liberalism and his loyalty to a constitutional monarchy separated him from both committed monarchists and the Jacobins.

This ambiguity explains the different ways in which he was received. On his 1824–25 trip to the U.S., he was given a triumphant welcome: parades, ceremonies, and fiery speeches presented him as a foreign “founding father,” one of the last witnesses to the adventure of 1776. In France, he remained a divisive figure, celebrated by liberals, hated by radical revolutionaries and monarchists alike, and subsequently nearly forgotten.

Since Lafayette, Franco-American relations have constantly oscillated between fascination and rejection. Since the eighteenth century, France has viewed America as a democratic laboratory, a space where social mobility and economic energy seem to hold the promise of a different future. In his Democracy in America (published from 1835 to 1840), Tocqueville expressed both admiration for a more egalitarian society and fear of a leveling that threatened the freedom of thought. Conversely, America has long seen France as the cradle of a refined culture and a prestigious intellectual tradition, while simultaneously distrusting it.

These overlapping perceptions are rife with misunderstandings, and Lafayette, admired across the Atlantic and controversial in France, encapsulates this ambiguity.

TWO CONCEPTIONS OF DEMOCRACY

In the U.S., the Constitution of 1787 established a system of checks and balances intended to prevent any excessive concentration of power. Freedom of expression, guaranteed by the First Amendment, is conceived as absolute: the state cannot restrict it, even in the face of statements deemed shocking or extreme. Trust rests on the marketplace of ideas: it is public debate that must distinguish truth from falsehood.

In France, the Declaration of 1789 also affirms liberty of expression, but it immediately places limits on it: “except what is tantamount to the abuse of this liberty in the cases determined by law.” The state sees itself as the guarantor of national cohesion and civic unity. Freedom is a right, but it must be exercised within the framework of the general interest.

This can be seen as an explanation for various contemporary misunderstandings: Americans see certain French speech laws as an attack on freedom, while the French sometimes judge America to be too tolerant of abuses of public discourse.

Lafayette always defended freedom of expression in the widest sense. As an admirer of the American First Amendment, he fought in France for a free and independent press, while accepting that it should be regulated by law. This middle ground reflected his temperament: he rejected both unrestricted freedom on the one hand and censorship on the other.

Today, the comparison remains illuminating. The U.S. defends near-absolute freedom of expression, while France maintains limits related to public order and social cohesion. By oscillating between these two poles, Lafayette embodies the very dilemma of modern democracy: how can we reconcile individual freedom and collective responsibility?

Another central aspect of Lafayette’s commitment was his fight against slavery. From the 1780s, he advocated for the emancipation of enslaved people and, with his wife Adrienne, embarked on a project to set up an experimental colony in French Guiana with freed slaves. In his discussions with Washington, he never failed to return to the subject of slavery and his own opposition to it. Although his project failed, he remained a supporter of the Société des Amis des Noirs (French Society of the Friends of the Blacks) and was an advocate for abolitionist ideas until his death. Lafayette’s acute awareness of American contradictions lay at the heart of his American journey in 1824–25.

The struggle against slavery was a relatively minority preoccupation at the time: he was made aware of the movement through his reading, particularly the work of the Abbé Raynal, and through his acquaintances. As a result, Lafayette is now being looked at anew in contemporary debates on colonial memory and slavery. Here again, he embodies the attempt to mediate in an area of tension between two worlds.

Culture constitutes another area of contrast. Since the twentieth century, American cultural industries—film, music, television, and digital media—have dominated the world’s imagination. Hollywood, jazz, rock, and Silicon Valley have disseminated an American vision of the world based on individualism, mobility, and personal success. Joseph Nye used the term soft power to describe this ability to influence others not through force, but through culture and ideas.

France responded by developing the idea of the “cultural exception.” Since the 1980s, it has imposed broadcasting quotas to protect its audiovisual production, supported its national cinema, and promoted the French language. It defends the idea that culture cannot be reduced to a commodity and that it is legitimate to protect cultural diversity. In this area, too, Lafayette appears in retrospect as a middleman: his career consisted of importing American ideas into France and exporting French ideals, particularly those of the Enlightenment, to America. His abundant correspondence shows how he constantly took pains to welcome Americans spending time in France, as evidenced, for example, by the numerous times the writer James Fenimore Cooper was a guest in Lafayette’s apartment on the Rue d’Anjou-Saint-Honoré in Paris or in his château at La Grange-Bléneau in Seine-et-Marne. Lafayette also encouraged and “placed” French people wishing to travel to the U.S. His library, too, is a rare testament to his vision of the role of culture in human, scientific, and technological progress: journals on agronomy, science, and law demonstrate his interest in sharing and applying innovations from the other side of the Atlantic.

STATE AND SOCIETY: TWO OPPOSING TRADITIONS

In the U.S., distrust of central power dates back to the struggle against the British monarchy. The state has long been limited in its interventions. Roosevelt’s New Deal and Johnson’s Great Society expanded the state’s prerogatives, but the dominant philosophy remains that of a society built on individual initiative and free enterprise. Welfare spending is fragmented and relies largely on private mechanisms.

In France, conversely, the state has always been central. It was the heir to the absolute monarchy, and it was reinforced by the Revolution and consolidated by the Third Republic. It remains the main body responsible for redistribution, education, and health. The welfare state is seen as a guarantor of equality and national cohesion. Here again, Lafayette straddled the border between these two conceptions, as evidenced by the debates surrounding bicameralism under the constitutional monarchy, in which Lafayette reprised his role as an admirer of the American system.

Such differences of opinion do not lead to a polarization, but to an ongoing dialogue. Debates on freedom of expression, colonial memory, and welfare all fuel intellectual and political exchanges. Each country uses the other as a critical mirror. American debates on civil rights and the Black Lives Matter movement resonate in France, where they feed into discussions on the memory of slavery and colonization. Conversely, Americans view French debates on secularism with both curiosity and anxiety, as they perceive them as restrictions on religious freedoms. These disagreements are not sterile: they force each country to think differently about its own history.

Today, then, French and American democracies face similar challenges: the rise of populism, social divisions, a distrust of institutions, and the influence of social media. Debates over the regulation of digital platforms illustrate a new divergence: America, home of the tech giants, is reluctant to restrict the power of these bodies, while France and the European Union are attempting to impose stricter rules in the name of digital sovereignty.

The climate crisis also raises the question of the role of the state and society. The U.S. oscillates between commitment and withdrawal, depending on the current administration. France advocates for a central role for public policy and for concerted international action. Here again, two visions of the relationship between individual freedom and collective responsibility are in conflict.

A PROMISE STILL TO BE FULFILLED

Lafayette, a celebrated hero on one side of the Atlantic, an ambiguous figure on the other, reminds us that the Franco-American relationship is neither a flawless fraternity nor a head-on opposition. It is made up of irreconcilable differences, but also of fruitful exchanges.

The Atlantic is not a dividing border, but a space for the circulation of ideas. If for two centuries France and the U.S. have looked to each other, inspired each other, and criticized each other, for two centuries, too, Lafayette has symbolized this dynamic: he does not embody a harmonious synthesis but how such tensions can prove productive.

At a time when democracies are weakened by polarization, misinformation, inequality, and global crises, studying Lafayette invites us to keep the dialogue between different traditions alive. The Atlantic promise is not one of uniformity, but of a permanent debate between two visions which, in their opposition, continue to enrich each other, just like the career of the general whose strongly held positions never got in the way of dialogue or, indeed, contradiction.

Translated by Andrew Brown

Vincent Bouat-Ferlier is the director of the Chambrun Foundation. His research focuses on Lafayette and his role in the American national narrative. He will be a Villa Albertine resident in 2026.

This essay first appeared in States, the annual magazine of Villa Albertine, published in January 2026.

Related content

Democracy in Two Worlds: A History of the Franco-American Alliance

Sister Republics: Two Visions of Liberty

The Declaration of Independence: A Global Legacy

Tocqueville: A Thinker for Uncertain Times

The Empty Throne: From Kings to Presidents

Archipelagoes of Art: A Transatlantic Museum Dialogue

My American Lessons

Who Shapes the Avant-Garde Now?

Big Theory: How America Brought French Theory to the World

Reel Love: A Story Starring French and American Cinema

Portfolio: Transatlantic Dreams

Between Fascination and Rivalry: 250 Years of Cultural Exchange