Archipelagoes of Art: A Transatlantic Museum Dialogue

By Laurence des Cars, director of the Louvre Museum, and Glenn D. Lowry, director of the Museum of Modern Art from 1995 to 2025

Two centuries after a revolution turned royal collections into public treasure, museums still upend expectations—placing art from across time and geography in conversation and reimagining their missions for the digital age. As Glenn Lowry steps down after a transformative tenure at New York’s MoMA, he and Louvre director Laurence des Cars reflect on the shared history that continues to link French and American museums.

STATES Let’s begin with a broad question about the shared history between France and the United States. How does the evolution of the museum—from a French model to an American one—help us understand the influence each country has exerted on the other?

GLENN LOWRY One can start by situating the origins of the public museum in France, with the Revolution and the massive transfer of royal collections into public hands. Museums in the United States emerged at roughly the same moment, animated by a similar spirit. Both reflect different ways of articulating democracy, of conceiving public space and public wealth—wealth here understood not as financial capital, but as intellectual and artistic capital.

Even before the Revolution, there was significant exchange between France and America. But during and after that period, a young nation like the United States looked to Europe for inspiration. Britain and France were particularly influential as America sought to articulate a democratic vision grounded in political freedom and expression. Museums became part of that project.

Where the two models diverged, however, is essential. In France, museums became instruments of state authority and power—a communitarian vision, one might say, in which the community takes precedence over the individual, and the state over the community. The United States, by contrast, saw museums as private initiatives, a civic responsibility carried by individuals. Thus, apart from the Smithsonian (founded in the nineteenth century) and the National Gallery of Art (established in the mid-twentieth century), the United States has no national museums. All others are municipal, state, or, more often, private institutions. This fundamental difference in how responsibility for culture is vested continues to shape the two traditions, even when certain models are shared.

Laurence, how would you characterize these models and the ways France and the United States still influence each other today?

LAURENCE DES CARS The origins of the Louvre, born in 1793, shaped it as a place of learning and discovery, where art history unfolds through the very architecture and layout of its galleries, offered to all who cross its threshold. Though not the first public museum to emerge—it arose in the wake of the birth of European museums—its defining originality lay in its democratic spirit and its ambition to nurture artistic education.

In the U.S., museums often grew from the vision and persistence of individuals. The famous painting of Charles Willson Peale as he unveils his “repository of natural curiosities”—a museum he established in 1784 in his house—epitomizes how personal initiative and museological ambition were intertwined. Even the Metropolitan Museum of Art, comparable in scope to the Louvre, was born from the shared efforts of a few individuals who resolved to create a national gallery of art in the 1860s.

These different origins yielded institutions distinct in governance, organization, and funding. Yet we both share a common impulse: to connect artworks with our publics, to preserve and enrich our collections, and to share them as widely as possible.

Glenn, are the two models converging or drifting apart?

GL Today, there is tremendous contact between the leadership of French and American museums. To be fair, this extends well beyond the two countries: directors of international museums are close colleagues who frequently collaborate on exhibitions, public programs, and publications, and who meet regularly to discuss shared concerns.

When I think of my closest colleagues, I immediately think of people at the Centre Pompidou, the Palais de Tokyo, the Musée d’Art Moderne de Paris, and of course the Louvre. American museums—including MoMA—often turn to these institutions for ideas, inspiration, and partnerships. We are living in a moment of intense collaboration and shared interests.

The Louvre has long partnered with American institutions, recently for instance with the Clark Art Institute for an exhibit on the painter Guillaume Lethière. How do you view exchanges between French and U.S. museums today?

LDC Throughout my career, I have always strived to promote collaborations between French museums and U.S. institutions—whether through major loans, temporary exhibitions, or professional exchanges. Such partnerships are vital to expanding our understanding of the collections and bridging, however briefly, the distance between masterpieces.

Two recent exhibitions highlight these mutual benefits. First, the exhibit The Met at the Louvre, which took place last year, displayed works from the Met’s Department of Ancient Near Eastern Art in the Louvre’s galleries. This unique dialogue revealed remarkable and unforeseen affinities between our collections.

Our partnership with the Clark Art Institute for the Guillaume Lethière exhibition was equally transformative, offering new insights into a long-neglected artist. Such curatorial dialogues foster fertile exchanges of perspective and expertise, inspiring fresh ways of conceiving and developing exhibitions. Strengthening these ties also deepens our own understanding of what we hold.

Illustration by Bérénice Milon

Glenn, what are the challenges museums face as they try to define themselves in the twenty-first century?

GL The challenges are many, and they differ from country to country. But several are universal. First, how do we address new publics and new artists? Second, how do we situate the great legacies of the past within conversations relevant to those publics and artists? Third, how do we adapt to the rapid transformation brought by artificial intelligence, digital platforms, and social media?

Museums must also build on their role as civic spaces, embracing broader and more generous global perspectives. When the Musée des Artistes Vivants (Musée du Luxembourg) was founded in Paris in 1818, or when MoMA opened in 1929, it was still possible—though not accurate—to believe that Europe and North America were the primary centers of artistic production. We now know that extraordinary practices have flourished across the globe.

I think it’s impossible today, even for museums whose collections are largely historical—the Met, the British Museum, the Louvre—not to think about how to engage artistic practices at a global scale. That, to me, is the central issue. Digital platforms and artificial intelligence are tools. But at the end of the day, museums remain about objects and artists.

Laurence, what do you see as the greatest challenges museums face in the twenty-first century?

LDC Museums are indeed facing major and diverse challenges. Very recently, the “Louvre heist” was a brutal reminder that museums are not fortresses. They are, by nature, open. The Louvre, like many other museums around the world, is not exempt from the increasing brutality of our societies. This complexity is at the heart of our daily work: our priority is to protect our cultural heritage while sharing it with as many people as possible.

Beyond security issues and at the core of these different challenges is the need to remain relevant for the contemporary world and to keep interacting with increasingly diverse audiences, who do not share the same expectations and interrogations when visiting our galleries. We must view our collections not as static repositories of knowledge but as living spaces that reveal the continual exchanges between cultures and civilizations and their translation into artistic forms. This does not mean erasing singularities and authorship but rather enlightening hidden, hitherto unknown connections between the artworks we exhibit. This is one of the key challenges for us today: to show that art history does not consist of separate traditions but in networks and entanglements. This is why I was delighted to invite Glenn Lowry to give a series of lectures last year to reflect on these crucial issues.

What does the history of museums teach us about the relationship between art and democracy today? Is the museum still, in your view, a democratic space, and what does that mean in the case of the Louvre?

LDC The Louvre was born from a democratic ideal inherited from the French Revolution. Its founding mission was to make the royal collections accessible to all, citizens of the new French state and foreign visitors alike. As a national museum, we continue to serve a civic and social purpose: the Louvre belongs to everyone.

The Louvre-Lens, opened in 2012 in a former mining region, embodies that commitment. More than a museum outpost, it was an investment in cultural and social renewal, a place for education, culture, and community cohesion. The experience of Louvre-Lens has transformed how we think about museums. It shapes the ways we reach new audiences—whether by opening satellite spaces or, more recently, presenting exhibitions in shopping malls to meet visitors where they least expect us. Today, to envision the museum as a democratic space means sharing its collections as widely as possible, ensuring that everyone—regardless of geography, background, age, or ability—can encounter the Louvre.

The Louvre welcomes nearly 30,000 visitors daily, which has an impact on the visitor experience. You’ve capped attendance and are planning a second entrance. Is managing scale and access now as central a challenge as curating collections?

LDC These two challenges are closely interwoven. The Louvre’s extraordinary popularity—nearly nine million visitors each year—makes it the most visited art museum in the world. It attests to its enduring power as a place of discovery and wonder. Far from considering attendance a burden, we must nonetheless acknowledge the consequences it has on visiting and working conditions. In addition to the explosion of overtourism, our museum has also been greatly affected by the critical increase in digital, environmental, and security concerns unforeseen forty years ago and the general wear and tear of the museum building.

The “Louvre New Renaissance” project, launched by the president of France, tackles these challenges to shape the Louvre of tomorrow. The museum will be completely renovated and redesigned for its millions of visitors. The entire building and its facilities will be revamped to strengthen their resilience to climatic hazards and ensure their accessibility. One of the key aspects of this project is the construction of new entrances on the easternmost side of the museum, known as the Colonnade du Louvre, that is supported by an international architecture competition. Furthermore, a new space for the Mona Lisa will provide the visitors with a new display tracing the painting’s history and offer them an unforgettable encounter with this iconic artwork.

The project will also include the construction of new accesses for the eastern side of the museum. This project aims at ensuring, through these important architectural undertakings, that wonder remains at the heart of every visit.

Glenn, I would like to touch on the notion of modernity. The model of the museum implies a relation to progress, to the future. But modernity is a tricky word. What does it mean to be a modern art museum in the twenty-first century, and how has that definition evolved since MoMA’s founding in 1929?

GL Modernity is a complex idea, and it can be approached in different ways. One way is to think of it as an era, a specific timeframe. Some might locate its beginnings with the advent of photography and film in the late nineteenth century, and its closure with events such as the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989. But this framework is problematic. It is difficult to identify any fundamental artistic rupture around 1990 equivalent to the advent of photography. Artists simply continued to make art.

At MoMA, one long-standing debate concerned our point of departure. My predecessors tended to situate it with Post-Impressionism, though that movement itself depended on Impressionism, which goes back to Manet and beyond. Personally, I find it more compelling to anchor modernity in the emergence of electricity, film, photography—technologies that transformed cities, reshaped our experience of urban space, and created new visual formats.

There is another way to understand modernity: not as a closed era, but as a mindset, a way of apprehending the present. In this sense, modernity is constantly shifting, redefining itself. This interpretation interests me far more than the idea of a finite period. It allows us to embrace both the contemporary moment and the intellectual space through which we define ourselves.

Alfred Barr, MoMA’s founder, famously imagined modernity as a torpedo moving through time: its nose is the ever-advancing present, its tail the receding past. While the metaphor has limits, it captures the essence of modernity as forward movement—not necessarily progress inthe linear sense, but the continual reengagement with the problems of the present. That, for me, defines the modern.

You quote Gertrude Stein: “You can be modern or a museum, but you cannot be both.” Is it difficult for an institution like MoMA to be this “torpedo” while also being a museum, with its building, collections, and traditions?

GL When MoMA was founded, it was essential to champion artists like Picasso, Matisse, Léger, Nolde, Kirchner, or Pollock. At the time, they were not universally embraced. Today, their importance is beyond dispute. They have entered the lexicon of art history, alongside figures such as Fra Angelico or David. From this perspective, our objective has been fulfilled: there is no further requirement to present arguments on their behalf.

Our task now is to champion artists who have not yet received the attention they deserve. Faith Ringgold, for example—an African American woman overlooked for decades, yet profoundly important. Or Jack Whitten, and many others whose marginalization may have been shaped by race, identity, or the market. It is our responsibility to make their case.

Here lies the tension. If we continue only to collect forward, while also preserving our past, we risk becoming simply another historical museum, like the Met, but with a different starting point. Over centuries, that starting point becomes increasingly irrelevant. Either we accept that and become a museum of art beginning in 1880, or we radically rethink our responsibility to the present. That, I believe, is what Gertrude Stein meant: you can be modern and committed to the present, or you can be a museum bound to history—but sustaining both over time is extraordinarily difficult.

Could you give an example of an exhibition that illustrated this challenge?

GL When I arrived at MoMA, the collection was displayed chronologically and largely by medium. Painting and sculpture occupied the center, while architecture, design, photography, and film were considered secondary. We had created a canon—useful, certainly, but also restrictive.

My goal was to move beyond canon-making. A museum devoted to the modern should not impose definitive hierarchies but rather propose hypotheses, opening new ways of seeing. This led to MoMA2000, a series of exhibitions that broke with strict chronology and medium divisions, elevating film, photography, architecture, and design to the same status as painting and sculpture.

At the time, we were criticized, even by those who had called for change. But today, this approach is widely adopted—by LACMA, the Pompidou, the Met, among others. Our aim was to make the collection more porous, engaging, and capable of embracing new practices without ossifying them into a rigid canon.

MoMA defines itself around modernity. The Louvre embodies history, heritage, and continuity. Yet both are constantly asked to stay relevant. Laurence, how do you reconcile the Louvre’s history with the need for innovation?

LDC The Louvre is not a contemporary art museum. Our galleries must portray accurately the depth of its history and collections. However, I am convinced that our masterpieces speak a contemporary language, that they are relevant in our time regardless of their date of creation. Museums are not static; they are continually reinterpreted through the questions of their time. Our collections mirror the world we inhabit, as well as the needs and anxieties of each era. To remain accessible to all, we must make their interpretation more intuitive. Digital technologies can play a crucial role in this, offering new ways to explore collections and shedding light on overlooked aspects of our institutional past. For the exhibition Mamluks: 1250–1517, we designed an immersive scenography that allowed visitors to grasp the physical reality of Mamluk art in new ways.

Let us turn to the question of universality. For much of the twentieth century, placing the public before the artwork was considered sufficient. André Malraux, for instance, argued that the masterpiece speaks for itself. Is this idea still present today?

GL Malraux is a fascinating case. Over his lifetime, he wrote extensively about art from many perspectives. His most important contribution, in my view, was the idea of the musée imaginaire: the recognition that a truly universal museum is impossible, since no institution can assemble all the world’s art. Instead, universality must be imagined—through ideas and images. In his time, he used photography; had he lived in the digital age, he would surely have turned to online platforms.

Crucially, Malraux understood that any conversation about art must extend beyond the European canon. He wrote about African art, Asian art, pre-Columbian art. He anticipated a broader and more inclusive understanding of the art world. At the same time, he acknowledged that every musée imaginaire is personal: his own was but one version, and he invited others to create theirs. This is why I prefer the term musée imaginaire to its English translation, “museum without walls,” which misses the point.

For me, the lesson is clear: the quest for universality, tied to European colonial ambitions, was always a noble but futile exercise. What is more compelling is to think of museums as ideas—as evolving works in progress shaped by collections, spaces, and intellectual frameworks.

The Louvre is often described as the archetype of the “universal museum.” Do you think art still speaks a universal language?

LDC The Louvre has always approached the notion of universality with a degree of ambivalence. Although the institution signed the “Declaration on the Importance and Value of Universal Museums” in 2002, it had also opposed the inclusion of extra-European works within its walls only two years earlier. Ever since I joined the Louvre as president and director, I have sought to explore the question of universalism on multiple levels, especially given the historical background of this concept, defined from a Eurocentric perspective. I do not see the Louvre as a “universal museum” in the sense of a place encompassing the entire breadth of human creation. It was never encyclopedic in scope. Yet it has always claimed a universal vocation—to speak to all who enter its halls. The challenge then is not to leave behind the universal as a remnant of a shameful past, but to face its historical roots, and reinvent it. Not as a closed inheritance of European modernity, but as a process built together, out of plurality. To rephrase Malraux, masterpieces speak through dialogue.

Glenn, you were trained as a specialist in Islamic art. Under your tenure, MoMA has expanded its scope beyond Europe and the United States. Is this a way of rethinking the universal?

GL I would not call it rethinking the universal. I admire institutions built around that ambition, and of course one cannot dismiss the great Enlightenment project of classification and cataloging. But my interest lies elsewhere: in the granularity of difference.

Artistic practices across Latin America, Asia, the Middle East, and India are not oppositional to European traditions; they are expansive, offering us new ways of seeing. Our role is to create contexts in which these differences are understood on their own terms. Greatness takes many forms. Leonardo da Vinci is a great artist—but so is Behzād, the Persian painter of the sixteenth century. Our task is to show why both matter, without collapsing them into a false equivalence.

There is an intellectual movement that pushes for the “decolonization” of universal concepts. Is this idea meaningful to you?

GL It resonates strongly, though I am cautious with the term decolonizing, which is often overused. Strictly speaking, decolonizing means confronting collections formed through colonization—such as those of the British Museum or the Louvre—and asking how they might be rebalanced today. That is an important task, but distinct from rethinking the relative weight of European versus non-European traditions.

I prefer the term rewiring. How do we rewire our institutional DNA to be more responsive in a world where knowledge and information are accessible everywhere? We can no longer regard India or China as distant or exotic. We are all part of the same conversation.

Laurence, having brought the Louvre Abu Dhabi into existence, what did you learn about presenting European art in dialogue with other traditions, and about questioning the Western gaze?

LDC The success of the Louvre Abu Dhabi rests on its ability to forge resonances between artworks, regardless of their era or place of creation, and to thread meaningful links between these collections and diverse audiences. This museum has a lot to teach us, especially as we need to reframe our narratives and our understanding of art history and foster an approach of art based on exchanges and porosities rather than on tightly defined categories.

The reopening of the Galerie des Cinq Continents, formerly known as the Pavillon des Sessions, reflects this new vision: it weaves together the Louvre collections with masterpieces from the Musée du Quai Branly–Jacques Chirac and other institutions, creating true conversations among artistic traditions and cultural heritages. In the gallery, we also used audiovisual tools to illuminate the paths and provenance of some of the works exhibited.

Yet we always speak from a certain perspective—European, American. Glenn, how do you avoid looking at other traditions from an ivory tower?

GL The first step is to acknowledge our position and be transparent about it. The second is to build partnerships with colleagues who bring different perspectives. For example, MoMA has developed a long-term relationship with M+ in Hong Kong, a leading museum of contemporary Chinese art. We know we cannot match their expertise, but by working together we enrich each other. Similarly, we are exploring research and exhibition collaborations with the Centre Pompidou.

We also created C-MAP (Contemporary and Modern Art Perspectives in a Global Age), a research initiative premised on learning in partnership with scholars and institutions worldwide. By building such networks, we expand our perspectives and inevitably change our acquisitions, exhibitions, and interpretations. Yes, MoMA is in New York, and that shapes our perspective. But by remaining open, collaborative, and self-aware, we can learn from others while contributing our own expertise.

You have often spoken of the museum as an “archipelago.” Could you explain this idea?

GL I owe much to thinkers like Édouard Glissant, who drew on the geography of the Caribbean to propose the archipelago as a model. I find it a powerful metaphor for museums.

Think of the museum not as a single chronological spine or a rigid sequence by medium, but as a constellation of independent yet connected “islands.” Each installation—whether devoted to a single artist, to Paris in the 1960s, or to the invention of photography—has its own integrity. Yet each is open to the others, creating a polyphonic, dynamic whole.

This approach breaks the hegemony of structure. It allows flexibility: installations can change, evolve, or be rearranged, creating new resonances. For the public, this is more engaging. It fosters complexity, but a complexity that remains comprehensible.

Over the years, as I reflected on Malraux’s musée imaginaire and on the ways we construct imaginaries, the idea of the archipelago has become my guiding metaphor. It captures the openness, diversity, and interconnectedness that a modern museum must embrace.

Glenn speaks of Glissant’s metaphor of the archipelago—museums as islands, specific yet connected. You often describe the Louvre as both a cultural institution and a diplomatic actor. How do you imagine the role of the Louvre within a global archipelago of museums?

LDC His metaphor is deeply relevant. It captures not only the internal logic of museums, which link disparate media, chronologies, and artistic trajectories, but also the networks that bind institutions worldwide. The Louvre itself is embedded within many such constellations, which all interact and exchange together: regionally, through close partnerships with French museums, and globally, through sustained dialogue with our peers. Plural, multisided dialogue ensures a coherent and thoughtful response to the transformations shaping the cultural world. In that sense, the Louvre—like other great museums—stands as a vital actor within a global archipelago of culture.

Interview by Raphaël Bourgois

Laurence des Cars is the president-director of the Louvre. Appointed in 2021, she is the first female director of the Louvre in its 230-year history.

Glenn D. Lowry became the sixth director of the Museum of Modern Art in 1995, a position he held until September 2025. In November and December 2025, he delivered a series of lectures at the Louvre, “I Want a Museum. I Need a Museum. I Imagine a Museum.”

This conversation first appeared in States, the annual magazine of Villa Albertine, published in January 2026.

Related content

Democracy in Two Worlds: A History of the Franco-American Alliance

Lafayette on Both Sides of the Atlantic

Sister Republics: Two Visions of Liberty

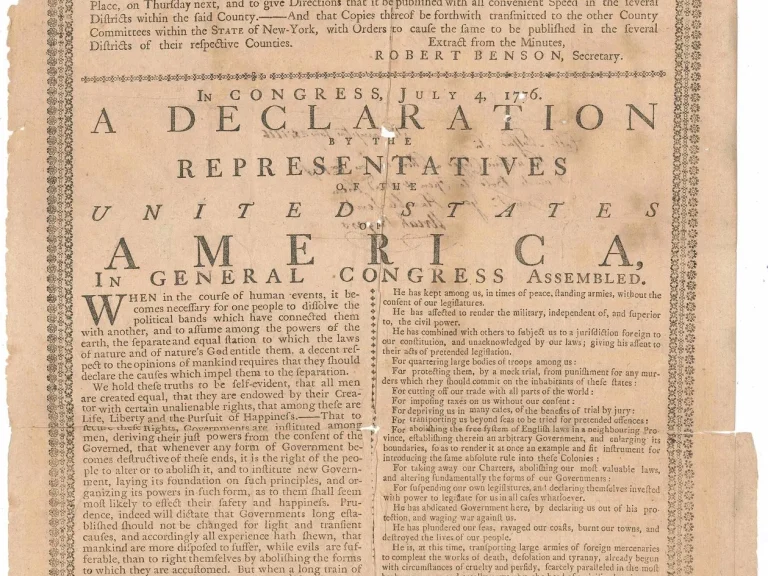

The Declaration of Independence: A Global Legacy

Tocqueville: A Thinker for Uncertain Times

The Empty Throne: From Kings to Presidents

My American Lessons

Who Shapes the Avant-Garde Now?

Big Theory: How America Brought French Theory to the World

Reel Love: A Story Starring French and American Cinema

Portfolio: Transatlantic Dreams

Five Years of Artists’ Residencies Across the United States