Big Theory: How America Brought French Theory to the World

Illustration of Michel Foucault by Thomas Daquin

By François Cusset, professor of American studies at Paris Nanterre University

In 1837 Ralph Waldo Emerson declared that America had “listened too long to the courtly muses of Europe” and called for an intellectual declaration of independence. Almost two centuries later Americans are divided over (among other things) French theory. Some blame the American obsession with theory for the country’s intellectual confusion, but, as François Cusset argues, theory has also helped the U.S. achieve a new kind of global influence.

What has been the most influential import from France to the U.S. over the last half-century? Is it the most radical-chic commodity, or the most controversial fashion, arriving directly from Paris? Instead of a perfume, a trend in haute-couture, a new new wave of independent cinema, or a political turn, the right answer could well be: theory. Yes, theory. Theory infusing curricula, academic careers, intellectual conflict, culture wars, the struggles of minorities, but also electronic music, neofigurative painting, cyberpunk science-fiction, and Web 1.0 hacktivism. Theory is seen as the source for a series of gender revolutions and the turn to identity politics, if not of progressivism as a whole. It is also a source of America’s radicalized neoconservative movement.

Illustration of Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari by Thomas Daquin

Theory is the source of all evil or all great advances, depending on where you stand in America’s ideological minefield. Theory may often be labeled “French” in the U.S., but it’s as if this Gallic qualifier is redundant, therefore useless: before being associated with such American names as Judith Butler, Fredric Jameson, or Edward W. Said, with their English counterparts such as Paul Gilroy or Stuart Hall, with such German names as Nietzsche, Marx, Theodor Adorno, or Walter Benjamin, or with such names from the Global South as Amartya Sen, Dipesh Chakrabarty, or Achille Mbembe, theory is first and foremost associated with a few French names from the last third of the twentieth century. These French names are familiar in American academe: Michel Foucault, Jacques Derrida, Gilles Deleuze, Jacques Lacan, Jean Baudrillard, and others.

And yet, to complete the paradox of theory, even though it is implicitly French or is always spiced with a Gallic flavor, it remains a quintessential American invention: imported texts and concepts were combined and mixed, chemically refined and processed, bottled and repackaged in universities in all fifty states. The ingredients may be foreign, the natural (or rather, textual) resources often European, the abstruse logic typically French, yet the final product is unmistakably American. Over the past fifty years, the U.S. has produced not only weapons, computers, internet giants, countless marketing trends—and a renewed tendency toward a populist, reactionary type of politics—it has also produced theory. And a lot of it.

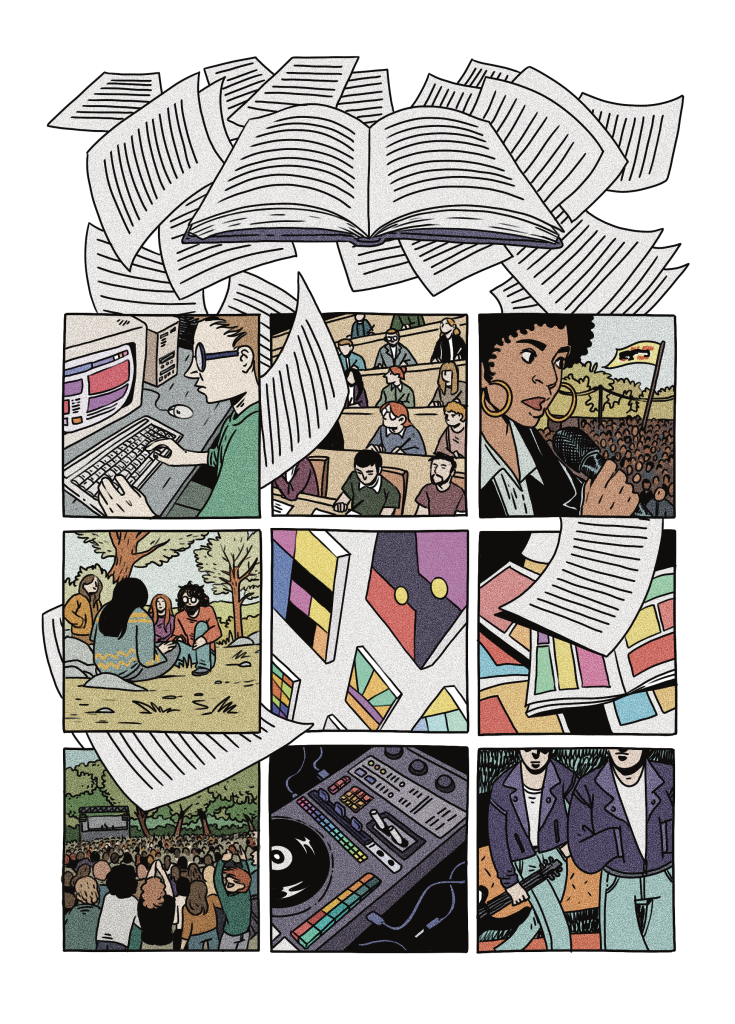

Illustration by Thomas Daquin

These dimensions have always made French theory a highly flexible, open-ended, inclusive category, to which its friends or foes will associate even more things: the former will add real liberty, anticonformism of all sorts, a loose community of interpretation (readers on the same wavelength), and an existential, emancipatory, California-style vibe reminiscent of self-help more than of classical philosophy. Foes will see in French theory the horrors of “cultural Marxism,” gender deconstructions, civilizational self-hatred, and terminal moral relativism (in the line of Nietzsche’s 1886 Beyond Good and Evil, widely quoted by the French). In its more than fifty years of existence, French theory has evolved over time, displaying changing facets according to its various audiences, contexts, and uses.

THE BIRTH (AND DEATH) OF STRUCTURALISM

It all started in Baltimore in 1966, when a group of French scholars were invited to Johns Hopkins University to present Americans with the mysterious vogue of “structuralism.” Once there, the French scholars declared the vogue already past: the young Derrida argued that the concept of structure was too rigid, centered, idealized, too obsessed with presence and fullness, and lacking in desire, variations, (fore)play, delays. Americans concluded that these French eggheads were “poststructuralists” (a label maintained ever since), and that what they didn’t yet call deconstruction had to do with drifts, postponings, deferrals, or whatever escapes full presence.

Less abstract and more fun, the 1970s is when the first texts from these peculiar French thinkers were translated into English and their strange paradigms ran into U.S. counterculture and the twilight of the “sex, drugs, and rock and roll” era. The hectic 1975 Schizo-Culture conference at Columbia University, for example, saw Deleuze and Foucault rub elbows with underground visionary writer William Burroughs and composer John Cage, while excerpts of their books were discussed and sometimes read aloud in alternative night clubs and S/M parlors of New York City’s infamous Bowery.

Illustration of Jean Baudrillard by Thomas Daquin

By the 1980s the whole thing became a must-read in fashionable campuses, especially in departments of literature eager to attract stimulating students—and ready to turn into the bastions of women’s studies, gay and lesbian studies, postcolonial studies, or cultural studies that they have become ever since. At the turn of the 1990s, minority activists from these elite campuses started recommending—under the term of “political correctness”—new ways of speaking that would counter sexist and racist violence (and keep silent skin color, gender orientation, a specific handicap) within common language. Conservative ideologues reacted by indicting a scary Orwellian language inspired by these “infectious” French texts—even though no French theorist ever proposed any new ways of calling each other.

In the 1990s a new type of counterculture emerging from the initial internet revolution and the rise of electronic music and politicized science-fiction found food for thought, and great quotes to spread virally, within that same loose French corpus. The Matrix saga by the Wachowski sisters (who were then brothers), experimental DJs such as Spooky or Shadow, anarchist geeks and left-wing libertarians inspired by the promises of the Web 1.0—as well as architects, painters, or novelists—all testify to a scattered pop-cultural influence on the part of these intimidating French philosophers at the turn of the millennium.

Traces of this French thinking can be found here and there, from undergrads’ reading lists to alternative media and even sometimes national polemics. In those years the verb deconstruct, unknown a decade earlier, was used by TV anchors to refer to what the Bill Clinton sex scandal was doing to the U.S. presidency, and by movie director Woody Allen as the title of his 1997 film, Deconstructing Harry. From graduate schools to public debate, notions taken from these French theorists (and duly redefined) started to permeate the new cultural left in the U.S., a young generation of progressives who refused to separate socioeconomic change from the more recent “rights revolution.” They exasperated and galvanized the New Right enough to allow, in reaction, for the rise of neoconservatives after 9/11 (in the name of “the clash of civilizations” and the defense of the West) and later of the Tea Party and further neo-Republican initiatives, direct sources of Donald Trump’s MAGA movement.

Illustration of Jacques Derrida by Thomas Daquin

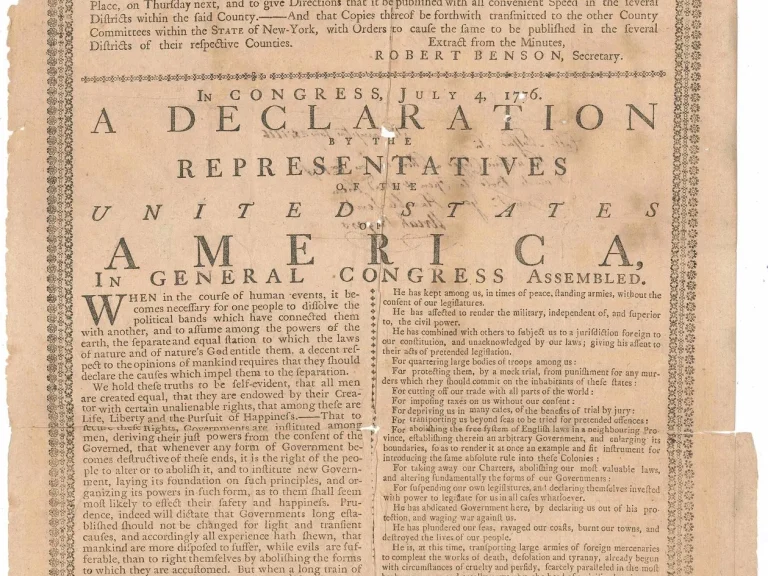

Which French ideas triggered such disproportionate effects? Michel Foucault’s work on “normalization” and the subjection of all of us to power-knowledge and disciplinary institutions. Gilles Deleuze’s philosophy of difference understood as an endless line of flight, a process of differentiation from imposed identities. Félix Guattari’s notion of desire as a productive force rather than a lack or a prohibition, as an exciting “factory” instead of some sort of hidden truth. Jean Baudrillard’s hypothesis about simulation as the power of signs and illusions to produce and ultimately replace what we call reality. Jacques Derrida’s misunderstood “deconstruction” as, not so much a method or strategy to criticize this and that, but rather what happens anyway to language, to meaning, to rationality, to relationality—and even to the 1776 Declaration of Independence, which Derrida famously deconstructed in a 1976 lecture at the University of Virginia. And not only did French theory transform American intellectual and cultural life, be it limited to specific circles, it also became, like anything successful produced on U.S. soil, a bestselling commodity for export throughout the world.

ENTREPÔT THEORY

Interestingly, French theory did reach Latin-American activists, African social scientists, South Asian historians, and Japanese artists not through direct export from France but, rather, via American mediation: in the English translations and useful anthologies published in the U.S. by university presses, through the lens of cultural leftists on American campuses, shaped by the interdisciplinary and pop-cultural vibes of intellectual culture in America—even when it ended up providing new arguments to demonize U.S. imperialism, from Kolkata to Beijing, Cairo to Mexico City, Moscow to Kingston, Jamaica. The international dissemination of these same texts and concepts initially fashioned in France has produced a brand new geopolitics of intellectual influence globally, arming progressives of all countries against the rising tide of populist conservatives: Indigenous struggles for equality south of the Rio Grande, bold historical revisions in today’s India, a rare Japanese critique of “infantile capitalism,” in sub-Saharan Africa a cry to de-westernize such concepts as “development” and “modernity,” a renewed Italian critique of post-Covid “biopolitics,” or provocative brands of movie criticism in Eastern Europe. All of these go against the grain of today’s dominant conservative politics, yet remain well and alive, inspiring young activists and students worldwide.

In the past few years, the best evidence of French theory’s lasting influence has been its indictment, among U.S. neo-reactionary ideologues but also from France’s conventional liberals, as the hidden and devilish source of what they all call “wokeness” or “woke politics.” The #MeToo and Black Lives Matter generation stands accused of either naivete or of imposing a new type of thought police (if not both), and also of being under the influence of French theory.

To the point that in today’s culture wars, relayed by social media and helping to do and undo governments, this ill-defined intellectual vogue from the 1970s known as French theory is seen as a direct belligerent, or at least a weapon: brandished by progressives, demonized by conservatives, partially read by both, or happily misinterpreted, it is thus doing very well—ready to keep playing an active role in the second quarter of the twenty-first century.

François Cusset is a professor of American studies at Paris Nanterre University. He is the author of French Theory: How Foucault, Derrida, Deleuze, & Co. Transformed the Intellectual Life of the United States.

This essay first appeared in States, the annual magazine of Villa Albertine, published in January 2026.

Related content

Democracy in Two Worlds: A History of the Franco-American Alliance

Lafayette on Both Sides of the Atlantic

Sister Republics: Two Visions of Liberty

The Empty Throne: From Kings to Presidents

The Declaration of Independence: A Global Legacy

Tocqueville: A Thinker for Uncertain Times

Archipelagoes of Art: A Transatlantic Museum Dialogue

My American Lessons

Reel Love: A Story Starring French and American Cinema

Portfolio: Transatlantic Dreams

Who Shapes the Avant-Garde Now?

Between Fascination and Rivalry: 250 Years of Cultural Exchange