Who Shapes the Avant-Garde Now?

Illustration by Bérénice Milon

By Nathalie Obadia, specialist in contemporary art and founder of Galerie Nathalie Obadia

French art once set the pace for the world. Then, after World War II, New York seized the avant-garde, building a powerful alliance of critics, collectors, and museums that pushed France to the margins. Nathalie Obadia explains how American soft power reshaped the global art scene, why French artists struggled for recognition in the United States, and why a new generation is finally gaining ground.

In 2015, Pierre Huyghe, one of France’s most internationally acclaimed visual artists, became the third artist invited to present an exhibition on the rooftop of New York City’s Metropolitan Museum of Art. This exhibition at the Met came ten years after Daniel Buren, at that time France’s most globally recognized and sought-after artist, was invited to exhibit across the Guggenheim Museum, another prestigious New York institution, marking the only instance in which a living French artist was invited to do so.

These exhibitions show the recognition of French art in America, specifically in New York, a city that remains at the heart of competitive soft power dynamics among Germany, the United Kingdom, Italy, and more recently China, South Korea, and the Gulf states.

Within this globalized art landscape, exchanges between France and the U.S. have always formed a unique partnership, due to the fact that Paris was the international art capital before the Second World War. Since then, the reception of French art in the U.S. and of American art in France have unfolded as two interconnected challenges.

The current situation cannot be understood without acknowledging how France’s artistic dominance, centered in Paris, gave way, from the Gilded Age onward, to the new economic, military, and at times almost messianic power of the U.S. Over the decades, New York became a symbol both of creative freedom and the triumph of capitalist principles within the art world. Its scene rapidly coalesced around a highly dynamic market driven by private collectors, many of whom were also influential museum patrons.

AMERICAN DOMINANCE

The publication in 1983 of Serge Guilbaut’s book How New York Stole the Idea of Modern Art sent shockwaves through French cultural and diplomatic circles. It detailed how activism, and alliances among the American art world and political and economic spheres, helped marginalize Paris and establish American dominance. Guilbaut examined the writings of art critic Clement Greenberg, who was the mastermind of the narrative around Abstract Expressionism. Greenberg propelled painters like Jackson Pollock, Franz Kline, and Mark Rothko to fame in New York and Europe, while systematically undermining the recognition of the Second School of Paris in the U.S. From the early 1950s, critical debates rooted in aesthetics already carried political undertones. Critics praised the bold, liberating gesture of Action Painting—as conceptualized by Harold Rosenberg and embodied by Jackson Pollock—as opposed to the more cerebral, less assertive Art Informel championed by Michel Tapié in France through such artists as Jean Fautrier and Jean Dubuffet, among others.

By the 1960s, a paradigm shift occurred, as the art world also emerged as an economic weapon. The United States, now the world’s dominant power, could increasingly set the terms of the art world. As critic Arthur Danto argued in his influential 1964 essay “The Artworld,” art takes shape within a broader world that is constantly being reshaped by political and economic forces.

By the 1960s, a paradigm shift occurred, as the art world also emerged as an economic weapon. The United States, now the world’s dominant power, could increasingly set the terms of the art world.

America’s art world expressed the triumph of capitalism and consumer culture, with Pop Art symbolizing the new society embodied by John F. Kennedy’s New Frontier. It was an example of American momentum across all domains: Pop Art was its reflection. It triumphed in the same year Danto’s text was published, when Robert Rauschenberg, supported by a strategic blending of art with politics and finance, won the Golden Lion at the Venice Biennale. It was the first time an American was awarded the world’s most prestigious art prize.

This came as a shock for France, long accustomed to being distinguished at the Biennale. Rauschenberg—whose work was far removed from abstract Action Painting, which had become the hallmark of American contemporary art—had claimed the symbolic prestige at the Venice Biennale. Meanwhile, French artists from the Nouveau Réalisme movement—who were close to Rauschenberg and whose works were often shown alongside his (including Arman, César, Yves Klein, Martial Raysse, Niki de Saint Phalle, and Jean Tinguely)—could have represented the French avant-garde in Venice. Instead, it was the U.S. that successfully combined the avant-garde, subversion, and political strategy to win the Golden Lion, whose prestige would long benefit its art scene.

What, then, led France to miss this pivotal avant-garde moment, one that would go on to complicate artistic exchanges between the two nations?

ADMINISTRATIVE ART

Several factors converged, such as a lack of coordinated strategy in artistic initiatives among political leaders like André Malraux, France’s influential minister of culture under General de Gaulle from 1958 to 1969, and Jean Cassou, chief curator of the future Musée National d’Art Moderne. There was also the near absence of powerful French avant-garde collectors, who could have advocated for the inclusion of Nouveau Réalisme artists in institutional exhibitions.

Influential French post-war critics were suspicious of American art and came close to rejecting it. There was the defeatism of art critics such as Pierre Restany, who watched Pontus Hultén, director of Stockholm’s Moderna Museet, support the success of Rauschenberg in Venice, despite Restany’s close ties to artists like Niki de Saint Phalle and Jean Tinguely. The period also saw the resignation of respected figures like art dealer Daniel Cordier, who published in 1964 (a month after Rauschenberg’s award) a letter announcing he was closing his Paris gallery. He soon thereafter opened a new space in New York City. Meanwhile, the structuring of the American art world was accelerating.

Leo Castelli spoke of the “team” formed by artist, collector, curator, and gallery to achieve international recognition for avant-garde artists. This was clearly visible at Documenta in 1964 and 1968, which saw a striking increase in the participation of American artists within the event created in 1955 in Kassel, West Germany, to support the rebirth of a German art scene in the wake of Nazism.

BRINGING BACK THE AVANT-GARDE

The effort to catch up after these two decades of inertia and missteps began late, with the election of Georges Pompidou in 1969. Supported by high-ranking public officials committed to the avant-garde, such as Robert Bordaz or curator François Mathey, Pompidou championed the creation of a museum of contemporary art in the heart of Paris. It was a powerful symbol: Paris sought to reclaim its status as the global arts capital.

Pompidou enlisted Pontus Hultén to help envision the new museum designed by Richard Rogers and Renzo Piano. It opened in 1977, despite attempts from Giscard d’Estaing, elected president in 1974, to derail the project. The French art scene still projected an image of traditionalism, leaving the dynamism of contemporary art to the U.S., which developed growing exchanges with West Germany and Italy. American artists frequently exhibited in these countries, while the Italians, led by the Arte Povera and later the Transavanguardia movements, and German painters such as Gerhard Richter, alongside Expressionists like Georg Baselitz and Anselm Kiefer, gained rapid recognition among American critics, museums, and collectors.

As Arthur Danto noted, this period saw an acceleration and therefore a normalization of the exchanges of contemporary artworks within the art world. Paintings were sold and resold at auctions, notably during the iconic sale of Robert and Ethel Scull’s collection in 1973, which saw the prices of American art reach record highs. This instilled lasting confidence in the art market.

To achieve an enduring market, the nature of artworks must allow for exchange, with paintings fulfilling the role of both instruments of power and financial assets internationally. American soft power was amplified by the strength of its market. Artists like Roy Lichtenstein, Rauschenberg, and Andy Warhol became internationally acclaimed. In France, conceptual practices were favored over painting, which further accelerated the imbalance between the two nations.

When I began working in the contemporary art world in Paris, at Daniel Templon’s gallery in 1988, I was struck by how static the situation was. American artists enjoyed exhibiting in Paris, but Cologne and Düsseldorf were more strategic places. Artists viewed Paris as a destination with sentimental value. It evoked fond memories of their pre-war predecessors who lived in the former capital of the arts. Yvon Lambert and Daniel Templon were the most Americanized of the French galleries, thanks to their ties with Leo Castelli and Ileana Sonnabend. That allowed them to showcase American artists like Donald Judd and Sol LeWitt.

In the late 1980s, the highly dynamic gallery Ghislaine Hussenot established itself and forged connections with New York’s avant-garde galleries, such as Metro Pictures and Andrea Rosen, enabling the exhibition of rising stars like Mike Kelley, Cindy Sherman, and Félix González-Torres. These artists didn’t expect much in the way of financial returns from French private collectors, but there were opportunities in being acquired or exhibited in French museums. (Few French museums were interested in American art: the notable exceptions were the Centre Pompidou, the Musée d’Art Moderne de Paris as well as the museums of Grenoble and Saint-Étienne, which began acquiring American artists early on.)

Illustration by Bérénice Milon

During this period, the French scene received significant subsidies from the Ministry of Culture, led since 1981 by Jack Lang under president François Mitterrand’s two terms, which granted unprecedented resources. Teams of young cultural innovators, such as Claude Mollard and Jean-François Chougnet, built the entire public art network across France and its overseas territories, establishing regional cultural affairs directorates (DRACs) and regional funds for contemporary art (FRACs), art centers, and numerous public commissions.

This organization was led by public officials and cultural civil servants, some quite influential, who promoted aesthetic trends that prioritized conceptual practices and installations. Consequently, the public sector overshadowed the art market, which was weak at the time. Collectors were staying discreet and exerting minimal influence on museums, where patrons’ associations were less developed and active than they are today.

This reinforced a perception that had existed in the U.S. since the 1960s: that the French scene was disconnected from the art market, which it denounced as being enslaved to American consumerism. This created a “French exception,” stemming from artists who were more theorists than visual practitioners, such as Daniel Buren, a member of the short-lived BMPT group (1967–68), and artists from the Supports/Surfaces group, active between 1968 and 1972, in which political disagreements often outweighed aesthetic concerns. By contrast, American artists from disruptive movements—including Carl Andre, Dan Flavin, Mike Kelley, and Paul McCarthy—critiqued American society without compromising their professional strategies. They aligned early with structured galleries like Paula Cooper or Metro Pictures, which helped them build their markets and achieve global recognition.

In the 1990s, the international art world grew increasingly competitive. The rising dynamism of Germany and the UK added to that of the U.S., which made the art world more critical of France. It was often asserted that France had neither great international artists nor significant contemporary art collectors. When I opened my gallery in 1993, these criticisms of France affected how its art scene was perceived, including at art fairs such as Art Basel, the most influential, where French galleries were not granted prime booth locations. To ensure sales to international clients, galleries were tempted to show American or German artists over French artists.

The imbalance between the U.S. and France deepened as American art increased its visibility in France in galleries, museums, and among adventurous collectors. In fact, American art implicitly inspired confidence, much like an industrial product combining technical robustness with strong branding. Meanwhile, French artists were less solicited abroad, especially in the U.S.

There were exceptions, of course. Ambitious figures like Daniel Buren and Christian Boltanski exhibited there early. But even these artists never reached the prices of their American peers or competed with their market. This created the illusion that French art was reclaiming its place in the U.S. However, few American galleries showcased French artists, despite diplomatic efforts that did not always resonate in the U.S., such as a coordinated series of exhibits of French artists across New York galleries in 1982, which was poorly received by critics, with the New York Times “Art People” column calling it “a French invasion,” and Le Monde being equally skeptical.

CONCEPTUAL RAPPROCHEMENT

In 1998, the two Guggenheim museums (including Guggenheim SoHo, which closed in 2002) hosted an exhibition of twentieth-century French art curated by Bernard Blistène, deputy director of the Musée National d’Art Moderne. The exhibit, which presented the French collections of the Centre Pompidou alongside those of the Guggenheim, revealed that the Guggenheim had lost interest in French art as early as the 1950s.

As noted above, the Guggenheim in 2005 presented Daniel Buren, then at the peak of his international recognition. This was spectacular, but the Americans took no risk as Daniel Buren did not compete with American conceptual artists, whose prices were higher. The same can be said about Pierre Huyghe, who, like most living French artists, was absent from major New York auctions. The most renowned French artists in the U.S. therefore had a peculiar status: on the one hand, they enjoyed significant institutional recognition, which allowed them to be shown in the country’s leading museums. On the other, they were nearly absent from the American private art market. This is also the case for two women artists, Annette Messager and Sophie Calle, who benefited from museum exhibitions and were represented by well-known galleries, Marian Goodman and Paula Cooper, respectively. These examples are often seen as symbols of French artists reclaiming their place in America. But the reality of the American art world was quite different.

The most renowned French artists in the U.S. had a peculiar status: on the one hand, they enjoyed significant institutional recognition, which allowed them to be shown in the country’s leading museums. On the other, they were nearly absent from the American private art market.

The publication of “The Hierarchy of Countries in the Contemporary Art World and Market”—a report commissioned from sociologist Alain Quemin by the French Ministry of Foreign Affairs to assess the presence of French artists abroad, published in French in 2001 and English in 2006—was a further shock that revealed the fading presence of French artists from museums in the U.S. Quemin’s report became a taboo topic, often referred to as the “forgotten report.”

In 2006, Frédéric Martel, a French cultural attaché in the U.S. from 2001 to 2005, explained in a celebrated book the reasons behind the effectiveness and the success of American culture. In Martel’s analysis the U.S. reliably mobilizes money, audiences, and institutions to produce both “high” and popular culture at scale.

DIVERSITY

Beginning in the 1960s, the American art world was energized by political protest, especially against the Vietnam War. Its critical edge was later sharpened by the uptake of French theory—Deleuze, Derrida, Foucault, and others—whose concepts allowed American artists to challenge domestic power structures while extending America’s influence in global cultural debates.

The torch was passed to young intellectuals such as Kimberlé Crenshaw and Judith Butler, alongside other influential thinkers from cultural studies who trained a future generation of art critics, curators, and artists, exemplified by Nan Goldin and Glenn Ligon. Beginning in the 1980s, these new American tastemakers played a key role in promoting artists who addressed issues related to gender and sexuality, and later turned their attention to race.

The artists engaged in these critical movements found resonance in France, such as Barbara Kruger, Felix Gonzalez-Torres, and Cindy Sherman, who all exhibited early in galleries such as Ghislaine Hussenot and Gabrielle Maubrie. As early as the 1990s, they were acquired by a new generation of avant-garde collectors in France, led by François Pinault and later by Bernard Arnault.

African American artists like David Hammons, Kara Walker, Kerry James Marshall, and Mickalene Thomas entered numerous prominent French collections. This curatorial and commercial momentum gave the image of an America capable of confronting its past, aware of its ethnic diversity, and the struggles associated with them. France, by contrast, appeared stagnant and disengaged. This was paradoxical, since it was largely French intellectuals who introduced deconstruction to American universities, giving scholars the tools to interrogate the dominance of Western white male power.

France continued to promote post-conceptual artists, predominantly men, perceived as intellectual figures removed from any narrative approaches, such as Philippe Parreno, Cyprien Gaillard, and Céleste Boursier-Mougenot, who were presented in institutions and galleries in the U.S.

In 1997, the U.S. invited its first African American artist, Robert Colescott, to the American pavilion at the Venice Biennale. He was soon followed by several others, including Martin Puryear and Simone Leigh. By contrast, France waited until 2022 to present a French-Algerian artist, Zineb Sedira, in the French pavilion. In 2024, for the first time, a French-Caribbean artist represented France: Julien Creuzet, who also exhibits in New York at Andrew Kreps. This time lag in themes explored by American artists compared to French artists deepened the imbalance between American soft power and that of France in the U.S.

American activism, which keeps societal issues at the center of cultural production, has proved highly effective and expanded U.S. soft power in France. Since the 2010s, Paris has reemerged as a major global hub, rivaling London, with private institutions such as the Fondation Cartier, Fondation Louis Vuitton, Pinault Collection, and Reiffers Art Initiatives frequently championing African American artists and other underrepresented voices from the United States and beyond. The 2025 Pinault exhibition Corps et âmes—which featured no contemporary artists from France—made that shift especially visible.

This marks another divergence with the U.S., which gives the impression that Americans are more engaged than the French in postcolonial issues. Notably, the exhibition Echo Delay Reverb at the Palais de Tokyo, curated by the American Naomi Beckwith (who will be the artistic director of Documenta in 2027), focuses on this topic, highlighting the contribution of French intellectuals to American art scenes.

The current president of the Palais de Tokyo, Guillaume Désanges, emphasizes that the U.S. has often responded to these new philosophical trends more swiftly than France. Once again, America has proven its pragmatic ability to absorb positive contributions from foreign influences, in this case from France. By doing so, it has been able to reinvigorate its artistic scene. Its influence subsequently spreads internationally, maintaining the U.S. as the leading country in terms of curatorial and artistic trends.

REVIVAL

What I observe today, more than thirty years after opening my gallery in 1993, is a much more positive perception of France in the past decade among American art players. France has moved beyond its image of a country where art only exists because it is subsidized. The private initiatives led by numerous private collectors now intrigue Americans, who are more drawn to private and philanthropic projects. American galleries have set up shop in Paris, and American artists are far more interested in exhibiting in Paris than in Berlin or London. The French galleries are seen as far more structured and professional than those of the previous generation.

France has moved beyond its image of a country where art only exists because it is subsidized.

The dynamism of the French capital only reinforces the presence of American artists, as evidenced by Jeff Koons, who offered his sculpture Bouquet of Tulips in tribute to victims of the terrorist attacks in France in 2015 and 2016. It was to be installed between the Musée d’Art Moderne de Paris and the Palais de Tokyo, facing the Eiffel Tower: an eloquent symbol demonstrating that Paris remained a strategic site of soft power. After a three-year controversy, the artwork was ultimately placed in a more discreet location, behind the Petit Palais, in 2019.

Public museums, facing reduced resources, are less solicited by American art players. Consequently, private institutions have taken the lead. Today, one might hope that private foundations benefiting from the 2003 Loi Aillagon tax deduction on corporate patronage would focus on strengthening the visibility of French art. It is one of the key issues raised in the report commissioned by the Ministry of Culture, titled “Strengthening the French Art Scene,” submitted in May 2025 by Martin Bethenod. The report explores the implementation of quotas for exhibitions featuring French artists by the Musée National d’Art Moderne, the Centre Pompidou, as well as for acquisitions by the Centre National des Arts Plastiques.

FRENCH ARTISTS IN AMERICA

How has the French presence evolved in the U.S. in recent years? We see a shift toward emancipation and individualization among French artists and curators, who go to America to work to participate in programs such as those offered by Villa Albertine, which include Étant donnés (a program benefiting both French and American artists as well as museums and other institutions) and residencies across the U.S. for visual artists or curators.

The artists who benefit from these grants are aware that American art is open to outsiders, yet it remains highly protectionist. Some artists have also chosen to reside in the U.S., such as Guillaume Bresson and Claire Tabouret, as well as Camille Henrot, who, in addition to her videos, produces works more readily accepted by the private market, such as paintings and bronze sculptures. Living in the U.S. allows them to remain closely connected to the American art world, which is easier to navigate in the curatorial field than in the commercial market, even though most of them exhibit in American galleries or branches of French galleries.

Other French artists are beginning to enjoy long-term recognition, such as Laure Prouvost. Her singular approach to ecological and geopolitical challenges has led to her increasing visibility in American museums, where her fluency in English allows her to be regularly invited to workshops and gain greater recognition. The ability to work in English has allowed young visual artists and curators to secure a foothold in the American art world, something the former generations often lacked.

As of the fall of 2025, concerns about how foreign artists will be received in the U.S. have not materialized after the start of Donald Trump’s second term in January 2025; applications for grants and residencies have not decreased. Roxana Azimi’s article, “Is Trump’s America Still a Dream Destination for French Artists?” published in Le Monde, underscores this. French art world figures, curators, conservators, and artists have gained a certain maturity, and are moving beyond ideologies to see the U.S. as an inexhaustible source of inspiration, cultural research, and career opportunity. In the years ahead, this outlook should help rebalance exchanges between the U.S. and France, allowing more French artists to immerse themselves in the U.S. and benefit from a dual presence: within the curatorial circuit, and in American galleries and among American collectors. The French “team” could then prove more effective in promoting its national art scene in the U.S.

Translated by Vanessa Richard

Nathalie Obadia is a French contemporary art dealer who founded her eponymous gallery in Paris in 1993. She studied law and political science before dedicating her career to the gallery world. Obadia has shown both emerging and established international artists.

This essay first appeared in States, the annual magazine of Villa Albertine, published in January 2026.

Related content

Democracy in Two Worlds: A History of the Franco-American Alliance

Lafayette on Both Sides of the Atlantic

Sister Republics: Two Visions of Liberty

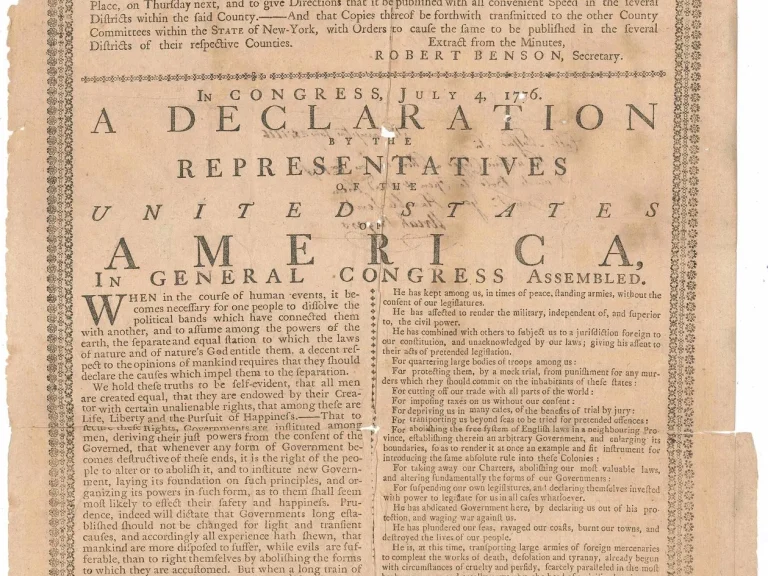

The Declaration of Independence: A Global Legacy

Tocqueville: A Thinker for Uncertain Times

The Empty Throne: From Kings to Presidents

Archipelagoes of Art: A Transatlantic Museum Dialogue

My American Lessons

Big Theory: How America Brought French Theory to the World

Reel Love: A Story Starring French and American Cinema

Portfolio: Transatlantic Dreams

Between Fascination and Rivalry: 250 Years of Cultural Exchange