The Empty Throne: From Kings to Presidents

Sketch for Le Serment du Jeu de paume by Jacques-Louis David, 1791.

By David A. Bell, professor of history at Princeton

Both France and the United States were born in revolutions that overthrew kings, yet neither has ever stopped searching for a leader to embody the nation. From Washington and Napoleon to de Gaulle and Trump, a look at how the two countries have wrestled with the paradox of a president who must lead—and embody—the nation.

In 2015, when he was still a presidential hopeful, Emmanuel Macron gave a magazine interview about the nature of French politics. Every democracy, he said, inherently suffers from a sense of “incompleteness.” And in France, “this absence is the figure of the king.” The traumatic execution of Louis XVI during the French Revolution, Macron argued, left the country with “an emotional, imaginary, collective void.” Charles de Gaulle filled the void with the monarchical presidency he created for the Fifth Republic, but after his departure from the scene “the normalization of the presidency again created an empty seat at the heart of political life. Yet what is expected of the president of the Republic is that he fulfills this function.”

Like most evocations of a deep, collective, national unconscious, Macron’s remarks had more than a tinge of romantic myth. But they point to one of the most striking parallels between the political life of France and that of its sister republic, the United States. Since the Age of Revolution, both countries have ceaselessly wrestled with the question of how a chief executive can serve simultaneously as a source of leadership, unity, and inspiration for a nation. Unlike most Western democracies, both countries have mostly resisted reducing their heads of state to mere symbols, like today’s European monarchs. But both countries have veered back and forth between a relatively weak executive and an all-powerful one—with France doing so more radically. The comparison is important for understanding both countries’ modern history—and also the political fragility they have in common, something that has become impossible to overlook.

FROM KINGS TO REPUBLICS

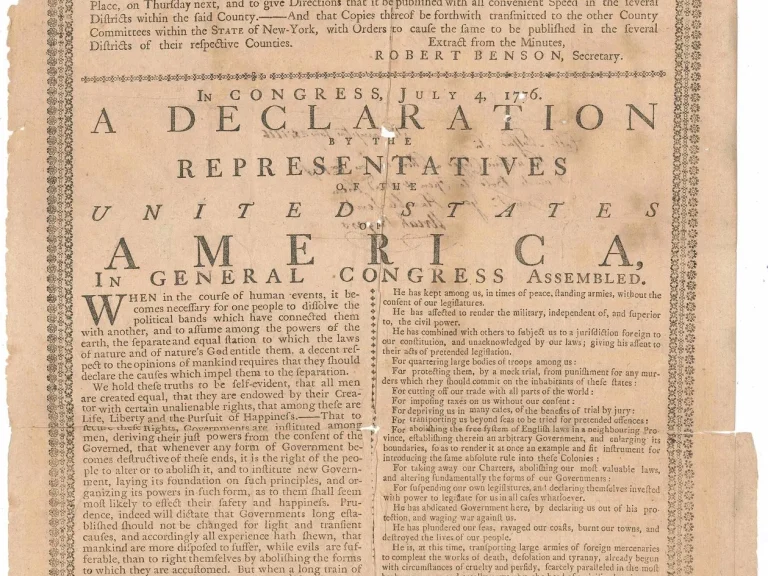

A shared monarchical heritage certainly played a role at the start of this history, for in the eighteenth century there were few more strongly monarchical societies in the Western world than Britain’s North American colonies and France. In the thirteen colonies, images of the king were ubiquitous, serving as proof to the (white) colonists of their status as freeborn Englishmen, equal to their brethren across the ocean. Until the very last stages of the prerevolutionary crisis, colonial leaders reserved their bile for the Parliament that had placed unjust tax burdens on them and hoped for relief from a still beloved King George III. Even when determined on a form of independence, they hoped they might still retain a connection with the monarch. Their love for George only shattered, and turned to hatred, when he rejected their “olive branch petition” and declared them traitors, in 1776. And almost immediately, they found a substitute figure in the handsome, courageous Virginia aristocrat George Washington, whose face quickly replaced that of the other George on prints, handkerchiefs, handbills, paper money, crockery, and much else. The song “God Save the King” was rewritten with the words “God Save Great Washington.”

France, meanwhile, can trace its monarchy back through the founder of the medieval kingdom, Hugues Capet, to the emperor Charlemagne, the Frankish king Clovis, and beyond him to the mythical Pharamond. In 1789, even zealous revolutionaries mostly saw King Louis XVI as an ally, not an enemy. After he accepted the transformation of the ancient Estates General into a revolutionary Constituent Assembly, charged with writing a new constitution, his popularity as the “Restorer of French Liberty” soared. Only after his failed attempt to flee the country and join with counterrevolutionaries in 1791 did opinion turn strongly against him. And even after Parisian militants and National Guardsmen stormed the Tuileries Palace in August 1792 and overthrew him, confused citizens from around France still wrote to the Assembly asking who would replace him as King. (No one did; France became a republic.)

Despite this shared monarchical heritage, the initial rejection of kings did lead both new republics briefly to eschew a powerful executive. In the U.S., Washington himself resisted attempts to grant him a crown, and at the end of the War of Independence ostentatiously resigned his commission in the Continental Army and returned to private life—to the relief of convinced republicans like John Adams, who had feared the rise of an American Caesar. At one point, Adams had even warned against “the superstitious veneration which is paid to General Washington,” and compared it to the worship of a graven idol. The United States emerged from the war a weak confederation of quasi-independent states. In France, during the Reign of Terror of 1793–94, some radical Jacobins urged Maximilien Robespierre to assume dictatorial powers, but the fussy, moralistic “Incorruptible” made a poor subject for a cult of personality. And in any case, in July 1794 rivals fearful of the guillotine overthrew and executed him. They then wrote a new constitution that divided executive functions among five “Directors,” the better to prevent any single man from assuming monarchical power.

But in neither case did this anti-monarchical interlude last long. As the Articles of Confederation proved increasingly unwieldy, George Washington himself urged a tighter union of the states, and agreed to preside over a constitutional convention. Its members designed a relatively powerful presidency, believing that the country needed a figure of real executive authority who could also, symbolically, put human flesh on the abstract bones of constitutional principle. They overcame worries about dictatorship because of the promise that Washington—who had by then proven his devotion to republican principles beyond doubt—would himself initially occupy the office and set the tone for his successors. In 1789, he won the first presidential election almost by acclamation.

In France, between 1795 and 1799, the “directorial” regime turned dangerously unstable, with three coups d’état in less than two years, even as the revolutionary wars turned against France and placed the Republic’s very survival in jeopardy. Under these conditions, a French Caesar seemed more of a savior than a threat, and the obvious candidate for the role was Napoleon Bonaparte, who at age thirty was already the most successful general in French history. In late 1799 he returned to France from his conquest of Egypt, and within a month had seized power, becoming First Consul. He then wrote a new constitution that accorded him enormous executive powers, while casting him as the guarantor of national unity after a decade of revolutionary turmoil.

In neither case did the revival of executive power signal anything like a return to traditional monarchy. Although enthusiastic American Protestants often compared Washington to biblical kings and even called him “godlike,” they recognized that his power rested on very different foundations from that of a monarch, deriving not from ancestry or divine sanction, but from the democratic choice of the people. If Washington enjoyed what social scientists term charisma, it was because ordinary people believed that he possessed exceptional human qualities and felt a deep emotional connection to him. Thanks to his example, some of this charisma became associated over time with the office of the presidency, providing it with a degree of respect that Washington’s successors could not have managed simply on the basis of their own personal qualities.

If Washington enjoyed what social scientists term charisma, it was because ordinary people believed that he possessed exceptional human qualities and felt a deep emotional connection to him.

France obviously turned in a different direction, with Bonaparte declaring himself Consul for Life in 1802, and then Emperor in 1804, and ruling as an autocrat. Still, in many ways his authority rested on foundations closer to Washington’s than to those of Louis XVI. For the first years of his regime, in fact, he insisted on his devotion to the Republic and compared himself to Washington on many occasions (notably when holding elaborate memorial services for the American president, who died in 1799). For a time, he also enjoyed genuine popular support. The act creating the Empire formally stated that “the government of the Republic is confided to an Emperor,” and Bonaparte took the title “Emperor of the French,” rather than the possessive “Emperor of France.” And despite the creation of a court and new nobility, accompanied by much pomp and circumstance, the Empire itself never gained real legitimacy. When the rumor spread in Paris in 1812 that Napoleon had died in Russia, political figures in Paris considered many possible options—but not declaring Napoleon’s infant son the new emperor. Napoleon himself stated on several occasions that his authority depended on his success—“upon each one of my victories.”

POWER WITHOUT UNITY

Since the early nineteenth century, on a purely formal basis the two countries’ political histories would seem to have diverged dramatically. The U.S. Constitution is still in place after more than two centuries, while in the same period France has had three kingdoms, five republics, two empires, and the collaborationist “French State” during World War II. Yet as the historian Pierre Serna observed in La République des girouettes, most of these French regimes have tried to govern from the center, with the hope of bringing a nation bitterly divided by the Revolution back together. And most have had a formally powerful executive—especially the Second Empire created by Napoleon’s nephew Napoleon III, who wrote in an early work that “the nature of democracy is to personify itself in a man.” Even under the parliamentary Third Republic of 1870–1940, the president was by no means a figurehead, and several holders of the office (Patrice de MacMahon, Félix Faure, and Raymond Poincaré) exercised serious political influence.

And so, the parallels did in fact continue. Interestingly, the period of the French Third Republic also represented something of a nadir for presidential authority in the United States. But the twin crises of the Great Depression and World War II prompted an enormous expansion of the federal government under Franklin Roosevelt. The Cold War and Lyndon Johnson’s Great Society social programs brought further moves in the same direction, and by Richard Nixon’s divisive time in office (1969–74) critics were already warning about an “imperial presidency.” During Ronald Reagan’s two terms (1981–89), conservative jurists began to cite the so-called “unitary executive theory,” according to which the president has complete authority over the executive branch, including functions defined by congressional legislation.

In France, after the quasi-dictatorship of Marshal Pétain under Vichy in 1940-44, the Fourth Republic reestablished parliamentary rule, but only for fourteen years. In 1958, after briefly assuming almost unlimited emergency powers to deal with the crisis provoked by Algeria’s independence struggle, Charles de Gaulle founded the Fifth Republic with a presidency whose formal authority outstripped even that of its American counterpart. De Gaulle did not remain regally above the political fray, as he had hoped. Still, thanks to his heroic wartime record and imposing personal qualities he commanded a degree of respect and popular support that few if any other French leaders have done in modern times, and set his new regime, at least for a time, on firm foundations.

Today, the ferocious political polarization in both countries has led to presidents on both sides of the Atlantic attempting to seize even more executive power—but for very different reasons, and with very different effects.

Today, the ferocious political polarization in both countries has led to presidents on both sides of the Atlantic attempting to seize even more executive power—but for very different reasons, and with very different effects. In the United States, Donald Trump has forged perhaps the most powerful ideological movement in American history, very much representing only one part of the electorate. Since returning to office in 2025 he has repeatedly, and with little or no constitutional authority, proclaimednational “emergencies” to radically reshape the federal government, assume direct power over independent agencies, and issue executive orders in matters ranging from trade policy to funding for university research to public health to control of the central bank. His supporters cite the unified executive theory as justification. In France, faced with the hopelessly divided parliament elected in 2024 by a fractured electorate, Emmanuel Macron has repeatedly used article 49.3 of de Gaulle’s Constitution to impose budgets and implement reforms without legislative approval.

In both countries, therefore, in some ways the presidency is more powerful than ever. Yet at the same time, in both countries, the president seems further than ever from being a unifying figure who symbolically incarnates the nation, as both Washington and De Gaulle managed to do at least to some degree—filling the “void” that Emmanuel Macron evoked a decade ago. Donald Trump does not claim to govern for all Americans, but only for the “real America” that does not include his political opponents. In the process, he has done much to strip his office of the charisma it inherited from Washington and transformed it into a raw instrument of political power. As for Macron, despite trying to pose as a “Jupiterian,” de Gaulle-like figure, remote from the political fray, he has found that in practice he cannot do so. The “normalization” of the presidency that he decried in 2015 turns out to have been inevitable, in the absence of overwhelming crises such as those of 1940 or 1958.

In both countries, there is also the apparent paradox of chief executives who control greater power than most of their predecessors in political systems that look more fragile and unstable than at any time in recent history.

David A. Bell is the author, most recently, of Men on Horseback: The Power of Charisma in the Age of Revolution. He teaches history at Princeton.

This essay first appeared in States, the annual magazine of Villa Albertine, published in January 2026.

Related content

Democracy in Two Worlds: A History of the Franco-American Alliance

Lafayette on Both Sides of the Atlantic

Sister Republics: Two Visions of Liberty

The Declaration of Independence: A Global Legacy

Tocqueville: A Thinker for Uncertain Times

Archipelagoes of Art: A Transatlantic Museum Dialogue

Who Shapes the Avant-Garde Now?

Big Theory: How America Brought French Theory to the World

Reel Love: A Story Starring French and American Cinema

Portfolio: Transatlantic Dreams

My American Lessons

Between Fascination and Rivalry: 250 Years of Cultural Exchange