Democracy in Two Worlds: A History of the Franco-American Alliance

Illustration by Bérénice Milon

By Robert Darnton, emeritus professor of history and university librarian at Harvard, and Carine Lounissi, professor of American history at the University of Rouen Normandy

Robert Darnton and Carine Lounissi are scholars of a revolutionary age driven less by armies than by books, pamphlets, and the surreptitious spread of ideas. Darnton, a pioneering scholar of the Enlightenment’s literary underground and author of The Revolutionary Temper, has spent his career tracing how forbidden texts helped ignite the French Revolution. Lounissi, author of Thomas Paine and the French Revolution, focuses on the intellectual history of the Age of Revolution, especially the interplay between the American and French revolutions.

On the eve of the Declaration of Independence’s 250th anniversary, their conversation for STATES returns to the improbable origins of the Franco-American relationship, when a French king found common cause with a struggling republic and when Paris and Philadelphia, Boston and Bordeaux, were bound across an ocean by a new belief: that people could govern themselves and reshape the meaning of democracy.

STATES How did each of you come to be interested in the other country’s revolution? Robert, perhaps we can start with you.

ROBERT DARNTON As an undergraduate, I hardly studied French history at all. I read a bit of French literature, and I learned the language rather late. Yet I shared the general American fascination with France—the country of liberty, of Sartre and Camus with their turned-up collars. In the 1950s and 1960s, France represented left-wing idealism, a spirit of revolt, and the French Revolution was part of that aura.

I only encountered the subject in graduate school at Oxford, where I followed a program in which the French Revolution and the Enlightenment were central. At that time, I was preparing to become a journalist and was even working part-time for the New York Times. But history, and particularly French history, ultimately took over, and I became a specialist in the field. Now, Carine, I imagine your path was different.

CARINE LOUNISSI Yes, it was. Like many French students, I first studied the American Revolution in classe préparatoire before entering university. At university, I focused on English studies—American history, British history, and so forth—but I was already fascinated by the American Revolution as a defining moment in French history.

As an undergraduate, I discovered Thomas Paine and his pamphlet Common Sense. I was struck by how someone like Paine could write such a powerful text, and then I learned that he had spent ten years in France and had written extensively about the revolution. That discovery anchored my interest. More broadly, I remain fascinated by revolution as both a concept and a historical process—especially by the connections between the American and French revolutions. French historians often insist that the only truly unique revolution was the French one, invoking a kind of “French exception” when they speak of the “Age of Revolutions.” But if you study the American case, you see that many ideas, concepts, and political forms were in fact invented during the American Revolution. So I came to the field through Paine, and today I work on the intellectual and historical connections between France and the United States in that revolutionary era.

French historians often insist that the only truly unique revolution was the French one, invoking a kind of “French exception” when they speak of the “Age of Revolutions.”

Let’s turn to those connections. In 1780, France sent an expeditionary force to support the American War of Independence. A Catholic monarchy was backing Protestant colonies that sought to establish a republic. How did this unlikely partnership come about?

RD On the face of it, the intervention seems absurd. Turgot, the finance minister, opposed it, predicting—accurately—that it would prove impossible to finance and would push the state toward bankruptcy. Yet despite these reasons to avoid involvement, England remained France’s great enemy. After the defeats of the War of the Austrian Succession and the Seven Years’ War, the French sought to reverse their losses and restore the balance of power.

There was also a cultural dimension. The figure of Lafayette, who at nineteen purchased a ship and illegally joined Washington, captured the imagination. Wounded at the Battle of Brandywine, he embodied a kind of romantic adventure that added symbolic force to the alliance. Still, I would stress that the intervention began above all as a diplomatic move, driven less by ideological sympathy than by strategic calculation.

In the early years, enthusiasm in France for the American cause was limited. If you look at the press—above all the Gazette de Leyde, published in the Netherlands—the reports initially focused not on America but on other theaters, such as India and the Caribbean. The wave of fascination with the American Revolution came only later. Would you agree with that, Carine?

CL Broadly, yes. The turning point came in 1778, with the alliance negotiated by Vergennes against Turgot’s advice. Vergennes was the true architect of the Franco-American alliance, working closely with Franklin. At the time, the difference in regime—a monarchy supporting a republic—was not considered an obstacle. Diplomats are often required to negotiate across such divides.

The deeper consequences emerged only later, as American writings and ideas began circulating in France, thanks to figures like Franklin and, less successfully, John Adams. It was through these exchanges that republican ideals entered French debates.

This shift is illustrated by perceptions of Washington. Before the Revolution, in France, he was remembered as the “traitor of Jumonville,” an episode that had tarnished his reputation. With the revolution, he was transformed into the hero of independence, a modern Cincinnatus. This change in image exemplifies the profound cultural reorientation of the period, even if the intense Franco-American moment itself was short-lived—ending, one might say, with the Quasi-War of 1798.

Deeper consequences emerged only later, as American writings and ideas began circulating in France, thanks to figures like Franklin and, less successfully, John Adams. It was through these exchanges that republican ideals entered French debates.

RD And from Washington’s perspective, this transformation was hardly automatic. He had served as an officer in the British army during the 1750s, when the Ohio Valley was a major theater of Anglo-French conflict. His early encounters with the French, including a disastrous mission in 1754 at Fort Necessity, were marked by mistranslation and misunderstanding. For him, France had been the enemy. Winning him over required time, diplomacy, and Lafayette’s extraordinary role as a courageous young officer who impressed Washington personally and later secured French support in 1779. But it is important to remember that neither Washington nor most Americans were naturally inclined toward France. The alliance was a pragmatic turn born of necessity as they turned against Britain.

CL In some ways, it was even easier for French intellectuals, aristocrats, and writers to embrace the American cause than it was for the Americans themselves to embrace the French. In France, Lafayette was celebrated, Franklin became a cultural icon, and republican ideas gained wide circulation. By contrast, Americans had long viewed France as an adversary. The convergence required effort on both sides, but in the end it produced a powerful, if temporary, moment of transatlantic solidarity.

But what was France’s actual role in American independence? Is there consensus on this? Was it primarily symbolic and intellectual, or was it a truly strategic and military contribution?

RD It was certainly a military contribution. Without the French fleet—under the Comte de Grasse—and Rochambeau’s army, I doubt Washington could have prevailed. His strength lay in guerrilla tactics, firing from behind trees and ambushing enemy units, but he could not have defeated the British in a pitched battle. The French military intervention was therefore crucial.

At the same time, French officers came into contact with this new country and returned home with reports, books, and a certain enthusiasm. Figures such as Chastellux published accounts that amounted to propaganda, spreading admiration for America. In my book The Revolutionary Temper: Paris, 1748–1789, I try to show how intellectuals fostered this enthusiasm and how it reached ordinary people in France—through songs, plays, and especially Boulevard theater. One of the greatest successes, L’héroïne américaine, enjoyed fifty-seven performances, an extraordinary record at the time. So from a decisive military intervention grew a wider cultural mythology about America that had a lasting impact.

CL I agree. The military role was decisive: Yorktown and the French fleet were indispensable to American victory. But beyond the battlefield, the alliance expanded diplomatic and commercial networks across the Atlantic.

French and American diplomats, merchants, and intellectuals were in constant dialogue. Figures like Franklin, Jefferson, and Adams found themselves at the crossroads of multiple influences, building a genuine relationship between France and the United States. Trade flourished briefly after 1778, but American merchants soon resumed commerce with Britain, much to Vergennes’ disappointment. He had hoped the alliance would secure lasting advantages for French commerce, but this expectation was not fulfilled.

Still, these overlapping networks—military officers, merchants, diplomats, intellectuals, and writers—helped weave the fabric of Franco-American relations in that period.

And what about the Enlightenment? In France, we often like to believe that our revolution was rooted in philosophy and Enlightenment ideals. But when it comes to America, was the Enlightenment really a determining factor?

RD The Enlightenment certainly mattered, but perhaps not in the way we usually imagine. It was long believed that Montesquieu, Voltaire, and Rousseau provided the key intellectual foundations of the American Revolution. More recent scholarship—by Bernard Bailyn and his students, among others—has shown that the strongest ideological currents in the colonies derived instead from seventeenth-century English political thought.

The Enlightenment certainly mattered, but perhaps not in the way we usually imagine.

The most important influence was probably James Harrington, whose Oceana celebrated republican government with voting rights, a free press, and a citizenry of yeoman farmers. His work, along with that of Sidney and Milton, provided a powerful ideological arsenal that Americans knew well before the Revolution.

That said, French influences were also present, if less central. For example, Harvard’s library holds an English translation of the scandalous bestseller La Vie privée de Louis XV—a four-volume, illicit history of the French court from 1715 to 1774. Our copy bears George Washington’s signature on the title page. So even Washington was reading subversive French literature, alongside the classics of political philosophy. These multiple layers of influence must all be taken into account.

CL The American Revolution mobilized concepts that were already part of colonial political practice. By the 1760s, colonial assemblies had become central institutions, producing constitutions and texts affirming the rights of colonists. There was thus a long-standing American tradition of political writing and constitutional experimentation.

This was, of course, a limited democracy—restricted to white male property owners—but it was nonetheless far broader than in Britain, where only about 5 percent of the population could vote. In the colonies, between 60 and 80 percent of white men with property had suffrage. So the Revolution built upon this tradition of local democracy.

English legal and constitutional thought also mattered: William Blackstone’s Commentaries on the Laws of England provided a framework for understanding rights and common law. Montesquieu and Locke were influential as well, but often as confirmation of ideas already rooted in American practice. In short, the revolution drew both from philosophical sources and from the lived democratic experience of the colonies.

RD I think Carine is right to emphasize practice—the lived experience of colonial politicians. And we should not forget that Britain itself had undergone two revolutions in the seventeenth century.

The Revolution of 1640–60 produced an extraordinary body of pamphlet literature, taken up by Milton, Sidney, Harrington, and later Locke. The so-called Glorious Revolution of 1688, long dismissed as a mere palace coup, is now seen as much more significant, even revolutionary. These precedents form the intellectual backdrop to the American colonists’ political practice.

That raises another question: having considered the intellectual and practical influences on the American side, what then was the American influence on France? That, too, is a vast subject.

The book that most shaped French perceptions of America was an extraordinary work titled Letters from an American Farmer. It was written by Hector Saint-John de Crèvecoeur, a Frenchman who had come to North America as a surveyor and mapmaker with the French forces during what we call the French and Indian War. He later settled in New York, married an American, and raised three children over twenty years.

In 1781, while traveling back to Normandy, he carried with him a journal he had kept. A London publisher encouraged him to turn it into a book, which became a minor hit in English. Soon after, Crèvecoeur went to Paris, where he was taken up by a fashionable salon, bathed in Rousseauist ideals, whose hostess was reputedly the model for the heroine of La Nouvelle Héloïse. Surrounded by writers such as Target and Saint-Martin, Crèvecoeur—seen as a rustic “American Frenchman”—had his book translated in 1782.

The French version bore little resemblance to the original. What had been a slim English volume became two thick French tomes, infused with Rousseauist sentiment, radical ideas about equality, and the vision of a Supreme Being speaking through nature to humble American farmers. Almost unreadable today, it nevertheless established a powerful myth of Americans as simple, egalitarian, virtuous, and close to nature.

A further translation in 1787 took even greater liberties, introducing an invented chapter about settlers literally signing a “social contract” to create a utopian society in the wilderness governed by the general will. This extravagant Rousseauist construction offered a revolutionary picture of America and became the single most popular book on the United States in France. The case of Crèvecoeur shows how mythmaking shaped French perceptions of America in the years preceding 1789.

Carine, what about the influence of the American Revolution on the French Revolution?

CL I would say that the turning point came only with France’s own financial and administrative crisis of the late 1780s. By 1787, with the convocation of the Assembly of Notables, many French politicians and writers began looking to the United States not as a direct model to import, but as a potential counter-model to Britain.

Throughout the eighteenth century, the British constitution had been celebrated as the finest in the world. But in the second half of the 1780s, authors such as Condorcet began to examine the American system as a new point of reference. It encouraged reflection on representation, the rule of law, and suffrage, and on how French institutions might be reformed.

Before this moment, French discussions of the American Revolution focused above all on commerce and geopolitics. Writers debated whether the Revolution would trigger a “general revolution” in trade, providing Europe with American products that might even prevent famine. They also discussed the colonial question—especially the future of Saint-Domingue, what is now Haiti. In 1784, the exclusif (the French commercial monopoly with its colonies) was modified into the exclusif mitigé, allowing limited trade with other European powers. Thus, in the early 1780s, America was primarily discussed in economic and colonial terms, not as a political model. It was only with the French crisis of 1786–87 that American institutions began to inspire broader political reflection.

RD Lafayette illustrates this transition. In 1787, he sat in the Assembly of Notables. At first he was silent, a young man reluctant to speak, until finally he denounced Calonne, the despotic finance minister, in forceful language. By then, Lafayette was in close contact with Jefferson, whom he saw almost daily at the salon of the Duchesse d’Enville. This Jefferson–Lafayette connection proved important at that moment.

But there were competing images of America. Jefferson himself was appalled by the distorted view presented in Raynal’s Histoire philosophique, and when Démeunier drafted the entry on America for the Encyclopédie Méthodique, Jefferson found it riddled with myth and error. He spent hours correcting it before giving up. Meanwhile, figures such as Filippo Mazzei—an Italian who had lived in Virginia and later Paris—published articles and a book attacking the romanticized French vision of America.

The debates became polemical. Mirabeau weighed in. Condorcet sided with Jeffersonian realism, while Jacques-Pierre Brissot, later leader of the Girondins, fiercely attacked Chastellux, Jefferson’s friend. The result was a swirl of ideological warfare: Condorcet signing pamphlets as “a Bourgeois of New Haven” (after receiving honorary citizenship there), Brissot as “a Philadelphian.” These exchanges reveal the intensity of the ideological battles surrounding the “cult of America” in France in the late 1780s, particularly from the Assembly of Notables to the eve of the Estates General.

CL One key issue at the time was slavery. Northern American states had begun gradual abolition: Vermont in 1777, Pennsylvania in 1780, followed by others. Jefferson, however, was deeply embarrassed in Paris. A slaveholder himself, he struggled to justify both his personal situation and the persistence of slavery in the United States to his French interlocutors.

He even began translating Condorcet’s Reflections on Slavery in 1788, though he abandoned the project. Some historians suggest that this marked a fleeting abolitionist moment in his career. At the very least, it was the time when he most acutely felt the contradiction. Jefferson tried to counter idyllic depictions of America with a more sober image, but he also cultivated another mythology—that of the enlightened Virginian slaveholder who favored abolition, which was only partly true.

RD Indeed. Shortly afterward, Brissot and Clavière founded the Société des Amis des Noirs, adapting English abolitionist arguments to the French context. Its members included some of the revolution’s leading figures—Condorcet, Mirabeau, even Robespierre. Slavery thus became a central and explosive issue, especially given France’s immense stake in Saint-Domingue. Figures like Barnave later defended slavery on commercial grounds, while Jefferson remained ambivalent, in stark contrast with Franklin, who freed his slave and embraced abolition.

Earlier you mentioned the way French historians often portray the French Revolution as the “true” revolution, in contrast to the American one. Does this come from the idea that the American Revolution was not a decisive, irreversible, or universal moment in the way the French Revolution was? That it lacked radicalism, mass involvement, or the desire to fundamentally transform society—elements we more readily associate with the French Revolution?

CL I think that interpretation has been increasingly challenged, particularly since the 1970s and 1980s. Historians like Gary Nash and Alfred Young have shown that the American Revolution was not simply the work of enlightened founders, but also a popular revolution with genuine social movements. Groups like the Sons of Liberty, around figures such as Samuel Adams in Boston, mobilized ordinary people, many of whom pursued ideas of equality.

So the old contrast—that the American Revolution was a sober constitutional affair while the French Revolution was a violent popular upheaval—is really a simplification. Both revolutions had elite dimensions and popular dimensions, and both combined intellectual ferment with mass action.

The old contrast—that the American Revolution was a sober constitutional affair while the French Revolution was a violent popular upheaval—is really a simplification.

RD I agree. More recent research on the American Revolution has revealed much more violence than was long believed. Some statistics even suggest that more people may have died in the American Revolution than in the French. Whether or not that is accurate, it was certainly a brutal conflict.

I also think the question “What is a true revolution?” is misleading. Revolutions differ in form and outcome. The French Revolution remains spectacular, with successive phases becoming more radical, even democratic. The American Revolution, by contrast, began republican but not democratic. The tendency to crown the French Revolution as the model—the revolution par excellence—was reinforced by the Marxist historiography of the mid-twentieth century. But today that monopoly has ended, and historians tend to see the French Revolution as one among many transformative upheavals, rather than the single archetype.

CL Another important shift in perspective has come from recognizing the Haitian Revolution as central to the Age of Revolutions. You cannot simply compare the French and American Revolutions in isolation. The Haitian struggle, and the wider Atlantic context, profoundly changed how historians understand this era.

The question of slavery, and of whether the American Revolution was to some degree an antislavery revolution, remains debated. The Philadelphia Convention certainly was not, but gradual emancipation in northern states did occur—beginning with Vermont in 1777 and Pennsylvania in 1780. So the picture is complex, but the Haitian Revolution compels us to broaden the frame beyond just France and the United States.

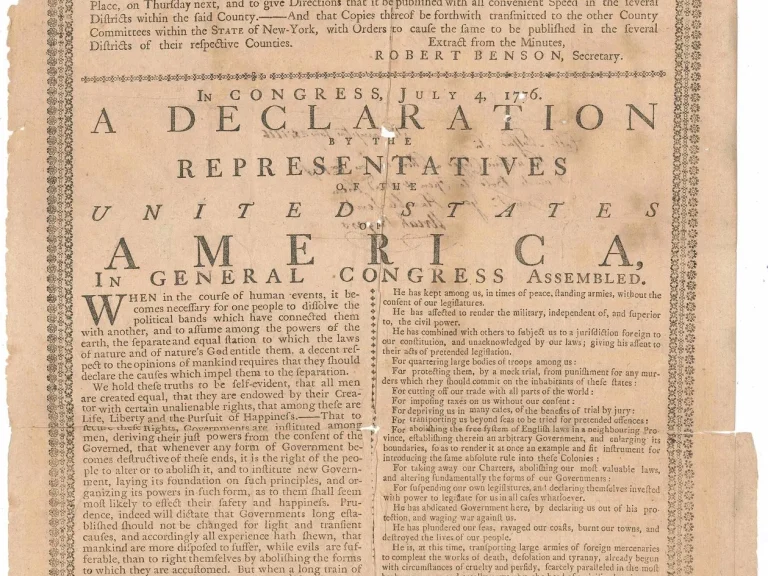

The Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen is still regarded as the text that introduced a universal dimension to revolution. By contrast, the American Declaration of Independence is generally seen as more narrowly political. Could we discuss the two texts and their legacies?

RD The French declaration was conceived with universal ambition, while the American declaration was a pragmatic document: a statement of independence from Britain. But the universalist aspiration of the French Revolution is undeniable.

Critics, of course, argue that this universalism was itself parochial, a form of Western ideological hegemony. I disagree. Philosophical traditions across cultures—including in India—have articulated normative principles comparable to natural law. To my mind, the critique of universalism as mere Western imperialism misses the point.

CL I agree. These principles are universal, not confined to the West. The debate recalls the eighteenth-century controversy between Burke and Paine. Paine insisted on universal rights of man, while Burke argued that rights are particular to each society and historical context. That debate, in some ways, continues today.

It is true that the Declaration of Independence was moderate in tone—its aim was diplomatic, to reassure potential allies like France that the United States was stable and reliable. Yet even there, the right of revolution is clearly stated: if a government becomes destructive of its ends, it is the duty of the people to overthrow it.

Moreover, if you look at state declarations of rights, such as the Virginia Bill of Rights of 1776 (authored by George Mason, a friend of Jefferson’s), you find principles remarkably similar to those in the French declaration of 1789: freedom of worship, freedom of the press, the equality of men. The problem, of course, is that many of these texts were written by slaveholders, which complicates their legacy and explains why figures like Jefferson have fallen so sharply in esteem today. But the universal dimension is nonetheless present.

RD What we are really discussing here are not only historical documents but enduring questions. Reading hundreds of pamphlets from France from 1787–88, I became convinced that the central theme was opposition to despotism—not the king as a person, but ministerial despotism. The same hatred of arbitrary power animated the American colonists. And that struggle remains relevant today.

We see new forms of despotism emerging in the United States: arbitrary arrests, deportations without due process, attacks on universities, on science, on culture, on the press. Despotism has not disappeared; it resurfaces. These debates about rights and universalism are not only historical—they cut to the bone of our present moment.

Interview by Raphaël Bourgois

Robert Darnton is the author of many award-winning works on French cultural history, and taught for many years at Princeton and Harvard. His books include The Great Cat Massacre, Censors at Work, and George Washington’s False Teeth.

Carine Lounissi teaches American history at the University of Rouen Normandy. Her research focuses on the intellectual history of the Age of Revolutions and transatlantic exchange during this period. She is the author of Thomas Paine and the French Revolution.

This conversation first appeared in States, the annual magazine of Villa Albertine, published in January 2026.

Related content

Lafayette on Both Sides of the Atlantic

The Declaration of Independence: A Global Legacy

Sister Republics: Two Visions of Liberty

The Empty Throne: From Kings to Presidents

Tocqueville: A Thinker for Uncertain Times

Archipelagoes of Art: A Transatlantic Museum Dialogue

My American Lessons

Who Shapes the Avant-Garde Now?

Big Theory: How America Brought French Theory to the World

Reel Love: A Story Starring French and American Cinema

Portfolio: Transatlantic Dreams

Between Fascination and Rivalry: 250 Years of Cultural Exchange