Sister Republics: Two Visions of Liberty

By Hugo Toudic, lecturer in political philosophy at Sorbonne University

The French and American revolutions drew on Enlightenment ideals, yet they produced divergent visions of liberty. Revisiting Montesquieu’s lasting influence—and Rousseau’s challenge to it—Hugo Toudic explores how the two republics, one built on representation and the other on popular sovereignty, continue to confront the difficult work of democracy.

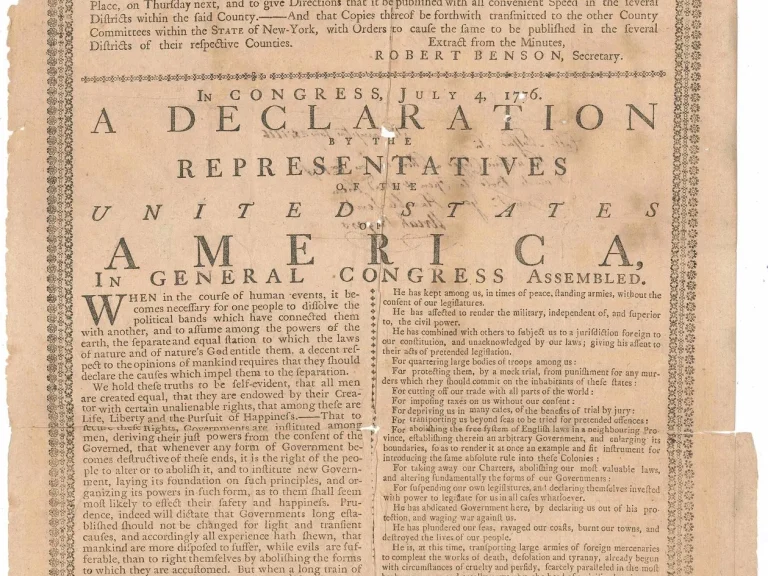

At the end of the eighteenth century, France and the United States gave birth to two of the oldest modern republics. Over the centuries, the two “sister republics,” as they have sometimes been called, have continued to compare themselves, both to lament and to console each other. The simultaneity of their revolutionary births—between 1776 and 1789 for the American republic and from 1789 for the French Republic—naturally invites comparison.

Of course, the French Republic has experienced many upheavals (we are already in its fifth incarnation, not counting those who call for a Sixth Republic). The American republic might seem more venerable, resting on the same Constitution adopted nearly two and a half centuries ago. Yet, in the case of both countries, profound changes have been made to their political systems.

As we celebrate the 250th anniversary of the Declaration of Independence, it may be useful to reflect on this long transatlantic history in order to draw lessons about the dangers that now test both republics.

TWO REVOLUTIONS: MONTESQUIEU AND ROUSSEAU

Much has been written about the differences between the American and French revolutions. The American Revolution has often been characterized as largely peaceful and intellectual, while histories of the French Revolution often focus on the barbarity perpetrated by opportunistic and bloodthirsty actors. Of course, we now know that these caricatured views of the two revolutions do not hold. The two young republics were in fact born from fruitful and polemical dialogues between the bourgeois elites of each nation, and the American Revolutionary War against the British Crown was itself extraordinarily violent.

Robespierre, Danton, Madison, and Hamilton were trained as lawyers and nourished by the great works of political philosophy. Montesquieu’s The Spirit of the Laws, published in French in 1748, served as a reference point for all political actors at the end of the eighteenth century. This widely read historical study of political theory and jurisprudence allowed the founders of both republics to reflect on various models of organizing power and society.

While the American founding fathers based their system on the separation of powers and political representation, the French founding fathers saw such separations as a renunciation of the democratic ideal.

While the American founding fathers based their system on the separation of powers and political representation, the French founding fathers saw such separations as a renunciation of the democratic ideal. They therefore turned to a great reader and critic of Montesquieu, Jean-Jacques Rousseau, who preferred the unity of the sovereign people and the general will over the separation of powers and representation. While it is perhaps reductive to say that American republicans are direct heirs of Montesquieu and French republicans the spiritual children of Rousseau, studying the relationship of the men of that time to these two major thinkers on political law allows us to better understand the serious difficulties faced by France and the United States.

POLITICAL REPRESENTATION

The ideological filiation between the French revolutionaries and the author of The Social Contract forced the former into contortions to overcome the prohibition on political representation. While Montesquieu praises the invention of representation in the British system, Rousseau offers a harsh critique that profoundly influenced Robespierre and his colleagues: “The English people think themselves free; they are greatly mistaken; they are only so during the election of members of Parliament; as soon as they are elected, they are slaves, they are nothing. In the brief moments of their freedom, the use they make of it deserves that they lose it.”

Illustration by Bérénice Milon

The radicalism Rousseau displays in his condemnation of the representative mechanism haunted the revolutionaries until their fall. While some, like Sieyès, agreed that the nation exists through representation, they soon became a minority. Since the people are virtuous, since they are always good, the real danger is corruption: that of the king first, whose flight to Varennes proved that power could only return to the Assembly. Then, within the Assembly itself, that of the Girondins who betrayed the revolutionary ideal. Finally, that of the Montagnards themselves, first Danton, then Robespierre. While nothing in this macabre succession was inevitable, we can nonetheless hypothesize that it was partly linked to ideological difficulties. While the American Federalists had resigned themselves to relinquishing the virtue of citizens and elected officials as the heart of their republican government, the French revolutionaries refused to do so.

The American Federalists had resigned themselves to relinquishing the virtue of citizens and elected officials as the heart of their republican government; the French revolutionaries refused to do so.

By contrast, Madison and Hamilton used representation to attempt to demonstrate the superiority of the American political model. For Madison and Hamilton, the role of the people in the new republic was limited to elections. According to Madison, as he writes in the Federalist Papers, the large number of voters and thus the potential number of candidates is certainly not a flaw but rather a crucial innovation of the American system. As the number of citizens grows, interests diversify, and the probability that a political coalition becomes a majority and potentially tyrannical decreases. This is not the only advantage of the system, as it also allows for the election of an assembly that will be less partial regarding local interests. It also makes this assembly more capable of placing public interest at the heart of their legislative work. According to Madison, representatives of the people need not resemble them but rather be better than them.

If the argument is brilliant, it remains that both Madison and Hamilton were embarrassed by the fate of a category of the people that would play a major role in the political balance of the future Congress: slaves. The infamous three-fifths compromise in the Constitution—designed to artificially increase the representation of southern states by multiplying the number of enslaved people in these regions by three-fifths—thus rebalanced demographics in their favor. This iniquitous clause was in large part the cause of the Civil War that would devastate the United States from 1861 to 1865, causing more than 700,000 deaths and reshaping the nation.

JUDICIAL POWER

While slavery was the main cause of the conflict between southern and northern states, it took a U.S. Supreme Court decision to reach the point of no return. Indeed, although the U.S. Constitution mentions the creation of a Supreme Court, the court attracted little attention in the early days of the republic.

It was not until Marbury v. Madison that the significance of the Supreme Court’s power within the U.S. system first became clear. In this landmark case, the Supreme Court declared itself, on its own authority, competent to strike down any law that violated the Constitution. The decision paved the way for judicial review, i.e., the review of constitutionality.

The consequences of this ruling were fully understood only years later, when the Supreme Court issued another notorious decision in Dred Scott v. Sandford. Chief Justice Robert B. Taney declared that the Constitution did not give Congress the power to abolish slavery—that power belonged solely to the states. The immediate consequence of this decision was to force northern states to return escaped slaves to the South. The risk of a nation split in two by slavery, far from being resolved by Taney’s ruling, became even more acute and ultimately led to the Civil War.

Once the abolitionist North emerged victorious, a system of civil and economic disenfranchisement replaced slavery: Jim Crow. It then took courageous political leaders to demand recognition of the rights of all American citizens, formalized by the Supreme Court in 1954 in Brown v. Board of Education, which outlawed racial segregation nationwide. In the French Republic, the idea of a Supreme Court seemed incongruous for two reasons. First, France was built as a nation-state, not a federal state where multiple sovereignties could conflict and where a final arbiter would be needed. Second, it lies in the conception of the organization of the three powers. In the eyes of the French revolutionaries, legislative power belonged only to the people, exercised through their representatives. Judicial institutions inspired mistrust because they recalled the Parlements of the ancien régime. This meant the key political actors were those who held legislative and executive power, each trying to monopolize the law-making authority. Only much later did a substitute for the American court emerge, the Constitutional Council. Gradually, the Council judged itself competent on all laws, often serving as the contested arbiter of political decisions, from pension reforms to environmental protection laws.

SEPARATION OF POWERS

What unites these two old republics, through their particular vicissitudes, is this major political idea: the separation of powers. Over time, each power attempts to assert its dominance over the others. Today, and against all expectations, the executive in France has never been so weak. Conversely, it has never seemed so ambitious across the Atlantic. In itself, this is not a problem. The modern republic is a singular regime that can use political conflict to protect the freedom of its citizens. These two republics are like a pendulum; executive ambition can be healthy if it is counterbalanced by legislative and judicial ambition.

The modern republic is a singular regime that can use political conflict to protect the freedom of its citizens.

The real danger never lies in the competition among the three powers, but in one power asserting its strength over the others. The persistence of the two republics, so different and yet animated by the same principle of separation of powers, should not surprise us. As Montesquieu wrote in The Spirit of the Laws: “To form a moderate government, it is necessary to combine the several powers; to regulate, temper, and set them in motion; to give, as it were, ballast to one, in order to enable it to counterpoise the other. This is a masterpiece of legislation; rarely produced by hazard, and seldom attained by prudence.”

Two and a half centuries after their establishment, France and the U.S. still stand, a testament to the resilience of this political idea. Over the centuries, both republics have endeavored to extend the right to vote to the entire population, allowing a greater share of citizens to participate in political decisions. Yet our two republics currently face an unprecedented moment of crisis. While no political party questions the republican model, the measures necessary to defend the republic seem, to say the least, paradoxical.

In France, political instability following the dissolution of the National Assembly in 2024 appears to have fostered public support for a strong executive to end the crisis. In the United States, neither Congress nor the Supreme Court seem ready to counterbalance the ambition of the executive branch.

The American founding fathers believed that the genius of the modern republican system lay in the fact that it did not need enlightened and virtuous men. Competition among the three branches was to secure citizens’ freedom despite—or rather because of—the vices of elected officials. Yet, by electing George Washington as the first president of the United States, the supreme officer of the executive power, Congress appeared to depart from this principle. Should there not remain some measure of virtue, love of the common good, and self-sacrifice in those who govern us? Today, our two republics are more than ever suspended on this question.

Hugo Toudic is a lecturer in political philosophy at Sorbonne University. His dissertation examines Montesquieu’s influence on the Federalist Papers. Toudic previously wrote for States about how the European Union might draw inspiration from the Federalist Papers.

This essay first appeared in States #4, the annual magazine of Villa Albertine, published in January 2026.

Related content

Democracy in Two Worlds: A History of the Franco-American Alliance

Lafayette on Both Sides of the Atlantic

The Declaration of Independence: A Global Legacy

Tocqueville: A Thinker for Uncertain Times

The Empty Throne: From Kings to Presidents

Archipelagoes of Art: A Transatlantic Museum Dialogue

Who Shapes the Avant-Garde Now?

Reel Love: A Story Starring French and American Cinema

Big Theory: How America Brought French Theory to the World

My American Lessons

Portfolio: Transatlantic Dreams

Between Fascination and Rivalry: 250 Years of Cultural Exchange