My American Lessons

By Rima Abdul Malak, French minister of culture from 2022 to 2024 and executive director of L’Orient-Le Jour

Rima Abdul Malak’s tenure as cultural attaché placed her inside an American cultural scene that was bolder and more experimental than she expected—and more exposed. Her account of those years touches on the power of American universities, the rise of socially engaged art, and the evolving role of philanthropy, and offers a diagnosis of how to navigate the current moment, when institutions that sustain cultural life appear newly vulnerable.

When I arrived in New York in 2014 to step into the position of cultural attaché at the French Embassy, I had many stereotypes in mind. I imagined a cultural scene totally dependent on private funding, shaped by market logic and the priorities of foundations, and dominated by digital platforms and Hollywood studios. In short, a cultural world less free and less diverse than in France. I also assumed that in such a vast, inward-looking country, the cultural sector would have limited engagement with the international stage. I was fascinated, however, by the American “melting pot,” a society that saw immigration as a strength and gave greater visibility to minorities across every field.

Quickly, I learned to dismantle my clichés. During my first weeks in the U.S., living in New York’s East Village, I discovered independent theaters with bold programming like La MaMa and New York Theatre Workshop; movie theaters open to every genre and films from every country, at places like Anthology Film Archives; and a dense network of galleries, art centers, and artist-run spaces blurring the lines between the art market and the nonprofit world. A mattress salesman told me about his passion for Truffaut; neighbors invited me to performances in community gardens; and even Broadway defied my predictions. The Book of Mormon was, for instance, a masterpiece of biting humor filled with political subtext. My friends in France kept saying, “New York isn’t America.” True enough, but I found the same cultural vibrancy elsewhere, with blurred borders between public and private, art and social engagement, professional and amateur—in Atlanta, Chicago, Dallas, Los Angeles, Minneapolis, Philadelphia, and New Orleans.

My friends in France kept saying, “New York isn’t America.” True enough, but I found the same cultural vibrancy elsewhere, with blurred borders between public and private, art and social engagement, professional and amateur.

That was more than ten years ago. America welcomed me with open arms; every cultural partner I met was eager to develop projects with France and other Francophone countries. They shared with me their energy, openness, and ability to break down silos and topple hierarchies. They encouraged me to be bolder, freer, more experimental. Together we carried out remarkable residencies, performances, exhibitions, debates, festivals, and events across the country. Then, in 2016, came a shock: Donald Trump was elected president, launching a cultural war that he is now pushing to its extreme. Confronted with this emerging crusade, we strengthened the collaborative projects that united us; we pooled our efforts to defend common values, uphold education and culture, and build pathways that connect and gather rather than divide and exclude.

I took away several lessons from my American years. The first concerns the strength of universities, which are major cultural hubs across the country. Museums, orchestras, cinemas, festivals, artists in residence: their artistic programming is a constant fireworks display, designed both to animate campus life and nurture the intellectual curiosity of students. While several French universities have become multidisciplinary hubs brimming with life and innovation, like Paris-Saclay, most institutions of higher education are still far from matching the thriving environment characteristic of American campuses. Today, higher education, the pinnacle of American excellence, is under direct attack by Trump. It is precisely in this moment of upheaval that cooperation with American universities becomes more important than ever. We cannot watch American universities decline, for their weakening would herald our own. We must support them during this critical moment, welcoming their faculty and researchers to France, carrying out international initiatives together. Whatever it takes, we need to join forces to withstand the pressures of authoritarianism and those seeking to undermine academic freedom.

My second American lesson lies at the crossroads of art and social action. This field, known as “social practice,” was not new when I arrived in New York, but it was gaining recognition and significant private funding. I was impressed, for instance, by Rick Lowe’s Project Row Houses in Houston. Lowe describes himself as both an artist and a “community organizer.” With Project Row Houses, he renovated about forty houses to host both artists in residence and single mothers struggling to find housing. In Chicago, I became fascinated by the work of Theaster Gates and his Rebuild Foundation, with whom we collaborated on a long-term initiative. He undertook a vast rehabilitation of Chicago’s South Side, opening spaces dedicated to reading, music, sports, woodworking, African American cinema, and contemporary art. A similar approach unfolded in Los Angeles, where Mark Bradford founded Art + Practice, combining an exhibition program with support for at-risk youth. These African American artists, widely recognized and “validated” by the art market, sought to advance social justice and revitalize their neighborhoods. Their initiatives quickly influenced major institutions, leading to the creation of the Guggenheim’s Social Practice Art Initiative and the Met’s Civic Practice Partnership.

Illustration by Bérénice Milon

In France, many initiatives have emerged at the intersection of culture, care, and social engagement, but they have not received enough recognition or visibility. The divide between traditional cultural institutions and the sociocultural sphere remains deeply entrenched. While most cultural organizations are active in the social field, they do so mainly through initiatives conceived separately from their artistic programming. Many cultural projects aim to revitalize their regions, but they are rarely led by artists, especially well-known ones. And although these initiatives are often supported by the state or local authorities, they remain financially fragile, lacking the major philanthropic support that sustains similar projects in the U.S.

This leads me to my third lesson: the role of philanthropy. It was in the United States that I discovered philanthropy in its most structured form, true to its etymological roots in philos (loving) and anthropos (humanity). From a young age, children are encouraged to raise money by selling lemonade or organizing charity races for a cause. Volunteering is also widely promoted. In the U.S., more than 75 million people undertake volunteer work each year. In the cultural field, philanthropy sustains a vast ecosystem of organizations, artists, and events across the country. One Ford Foundation program, Creativity & Free Expression, has supported more than five hundred cultural organizations with a total of $230 million, a sum greater than the annual budget of the National Endowment for the Arts, the federal arts agency that the Trump administration has decimated. According to Giving USA, American philanthropy allocated $25 billion to the arts, culture, and the humanities in 2024.

Although cultural patronage has grown significantly in France since the 2003 Aillagon law and the introduction of tax incentives, no French foundation operates on the scale of the Ford, Mellon, Rockefeller, or Getty foundations. Few cultural foundations in France have a granting mission. Most see themselves as museums in their own right—the LVMH Foundation, the Pinault Collection, the Cartier Foundation. The same is true of private collections across the country. Aside from a few notable exceptions (Fondation du Patrimoine, Bettencourt Schueller Foundation, BNP Paribas Foundation), foundations that support a network of cultural actors, with annual budgets of more than €10 million, are extremely rare.

It was in the United States that I discovered philanthropy in its most structured form, true to its etymological roots in philos (loving) and anthropos (humanity).

Between the American model and French model, there is a third path worth developing: local patronage led by small and medium-sized foundations and companies. This could be encouraged by the state through additional tax deductions, more public-private projects, and donation campaigns. Cultural institutions across the country should receive support, training, and guidance to build circles of local patrons. At a time when philanthropy tends to become politicized—for example, through the Fonds du Bien Commun, launched with €100 million over five years by billionaire Pierre-Édouard Stérin to contribute to the “ideological, electoral, and political victory” of the far right—we need a philanthropic movement multiplied across the entire country, led by businesses and civil society in a unifying, nonpolitical spirit.

If I had to keep one final lesson from my years in New York, it would be the need to resist identity-based assignments and cancel culture. My ideal of the “melting pot” collided with the rise of debates around “cultural appropriation.” I understand their origins. They often stem from real wounds, histories of erasure, cultural looting, and a long-standing sense of having no place at the table. But why should a Franco-Moroccan choreographer who denounces the ravages of colonization not have the legitimacy to feel solidarity with the Native American cause? Must an excellent translator refrain from rendering the poetic voice of an African American author because he is not Black himself? Should artists avoid telling certain stories because they are not “theirs”? Should an actor regret having played a role on the grounds that he did not share the character’s sexual orientation? Isn’t the very mission of an actor to step into the skin of characters completely different from themselves, and to move audiences to their core?

In an era of identity-based tensions, the cultural sector cannot lock citizens into fixed labels; it must instead foster openness to otherness, show that identities are multiple and shifting, encourage dialogue, and protect artistic freedom. It is entirely possible to redouble efforts to better represent the diversity of society on stage, in films, or behind the camera; to fight against stereotypes; to transform training and production systems so that they no longer benefit the same people over and over; and still not restrict the freedom to write or interpret this or that role. The realm of art must remain a space of absolute freedom, within the limits provided by law, of course. One can denounce injustice, racism, and discrimination; be outraged by police violence; and fight for social justice without resorting to censoring lectures, films, or books, or banishing from public life any figure whose words might be perceived as “offensive.” Yes, art can shock. It can shift perspectives, stir unexpected emotions, and spark new reflection. That is its power and its very essence.

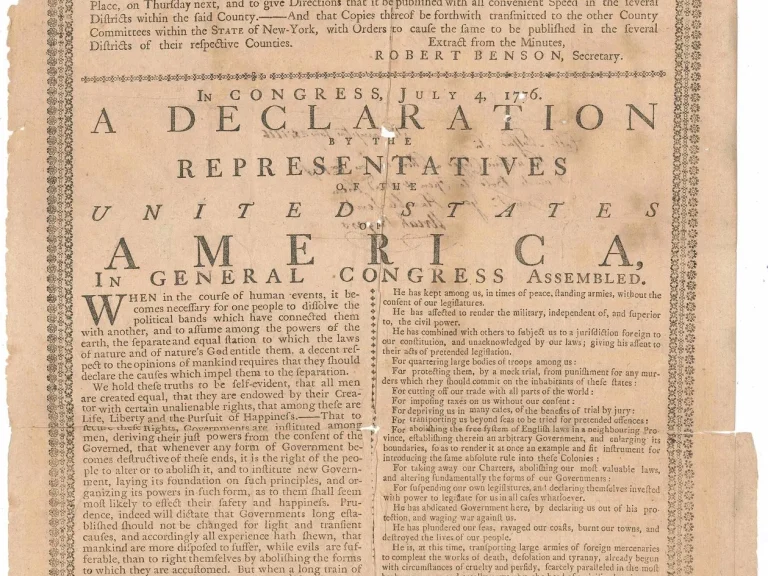

In an era marked by isolationism, inequality, and authoritarian temptations, culture is not a luxury. Culture is a way of standing upright. Looking to the 250th anniversary of American independence, I hope we can preserve this compass. Across the two shores of the Atlantic, what we can invent together is not a compromise but a true alliance: the alliance of humanism and imagination. An alliance that demands freedom, dialogue, and courage, so that culture remains what makes democracy possible: doubt, critical thinking, plurality of voices. A spirited, unruly space in which we can sketch the outlines of a fairer and more fraternal world.

Rima Abdul Malak was the French Minister of Culture from 2022 to 2024. She is executive director of the Lebanese newspaper L’Orient-Le Jour.

This essay first appeared in States, the annual magazine of Villa Albertine, published in January 2026.

Related content

Democracy in Two Worlds: A History of the Franco-American Alliance

Lafayette on Both Sides of the Atlantic

Sister Republics: Two Visions of Liberty

The Declaration of Independence: A Global Legacy

Tocqueville: A Thinker for Uncertain Times

The Empty Throne: From Kings to Presidents

Archipelagoes of Art: A Transatlantic Museum Dialogue

Who Shapes the Avant-Garde Now?

My American Lessons

Big Theory: How America Brought French Theory to the World

Portfolio: Transatlantic Dreams

Between Fascination and Rivalry: 250 Years of Cultural Exchange