The Freedom to Experiment: An Interview with Sivan Eldar

Photograph of Sivan Eldar © Daniele Molajoli

By Sivan Eldar, composer

When composer Sivan Eldar met singer Ganavya Doraiswamy and novelist Lauren Groff in 2021, a new kind of opera began to take shape. Inspired by an ancient Buddhist tale and by Doraiswamy’s South Indian musical heritage, The Nine Jewelled Deer evolved into a transatlantic collaboration involving director Peter Sellars, painter Julie Mehretu, and others.

Premiering in July 2025 at Luma Arles in partnership with the Aix-en-Provence Festival, the work defies the boundaries of traditional opera—blending human and instrumental voices, electronics, and improvisation. Its first spark came during Eldar’s 2022 Villa Albertine residency, which offered the freedom and support to test opera’s limits. Here, she traces the work’s unlikely evolution and reflects on how her time as a Villa Albertine resident helped her push opera into new territory.

STATES Let’s start at the beginning. What sparked the creation of your opera The Nine Jewelled Deer? It began with your encounter with the singer Ganavya Doraiswamy, I believe.

SIVAN ELDAR Yes. Ganavya is American. She was born in New York, grew up in Florida, and later spent time in South India, where she studied the abhang tradition of devotional poetry as well as Carnatic music with her grandmother. We met in 2021 during a residency at Civitella Ranieri, an American program in Italy. The three of us who eventually created this opera were there: Ganavya, the writer Lauren Groff, and myself.

At that time, Ganavya had already collaborated with the stage and opera director Peter Sellars on two smaller projects during the pandemic—one was a film, the other a theater piece. When we met, she spoke of her dream to work again with Peter but this time on something that would reflect her personal history—her grandmother’s legacy in particular—and that would involve a composer. She explained that in her previous collaborations with Peter she had been the sole musician, whereas she usually works in dialogue with other musicians.

She envisioned creating a dramaturgy that would tell a story in operatic form—even though, at the time, she knew as little about opera as I knew about South Indian music. She knew, however, that opera was Peter’s world and also mine, since at the time I was finishing my first opera, which I presented to the group. The convergence of her personal story, our musical connection, and our curiosity about what an “opera” could mean became the spark for the project.

Even today, the question of whether what we created is truly an opera remains open. If there is no Western-style lyrical singing, no traditional libretto, no conventional dramaturgical arc or staging—can it still be called an opera? Or is it rather a concert, a piece of theater with music?

What makes it an opera to you? Why do you want it to be labeled as an opera?

I should perhaps talk about my own background. Growing up, I went to operas with my grandparents, but opera was not a central part of my musical life. I was a pianist and composer, and as my studies advanced, I never imagined I would write opera—it didn’t feel accessible for a young composer.

That changed when I did a Fulbright in Prague and began working with physical theater. I loved the collaborative aspect of working not only with musicians but with performers in real time, shaping the work on stage as we went along—what in France we call l’écriture sur le plateau (writing on stage).

I was increasingly drawn to the world of dance and theater, even though music in those settings was rarely the central element. It was often underfunded, underdeveloped, treated as an addition rather than the heart of the research. I realized I wanted to create something for the stage where music was at the center, with time and resources to explore it fully.

That desire led me in 2018 to propose a project to Frank Madlener, director of IRCAM (the French institute dedicated to music and sound), where I had been studying and doing research at the time. I imagined presenting it at a contemporary music festival, not in an opera house. But Frank pointed out that an opera house or opera festival could offer rehearsal and production conditions that a non-opera institution could not: time for memorization, for deep collaboration, for musicians to really inhabit the score.

That was the moment I understood the paradox: the opera house, often perceived as the bastion of conservatism, is in fact one of the rare institutions where truly innovative musical work can happen—precisely because of the resources and time it affords.

That’s fascinating.

Yes, opera requires years of planning, and demands sustained collaboration with a director and writer. For my first opera, the main producer was Opéra de Lille, with a tour to Opéra national de Montpellier and Opéra national de Lorraine. Thanks to Lille, we could undertake highly ambitious experiments with IRCAM—like embedding seventy-two speakers under the seats. That would have been very difficult without the infrastructure of an opera house.

European opera houses, thanks to their public funding models, provide favorable conditions for new, experimental work.

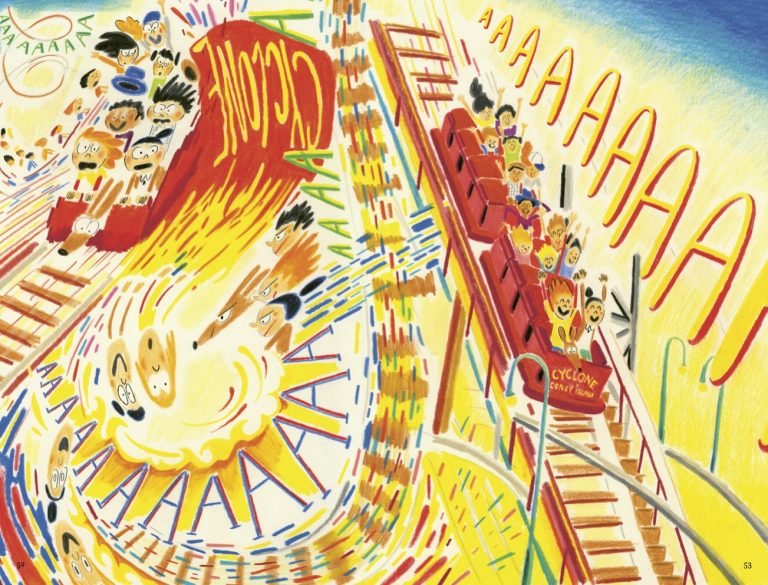

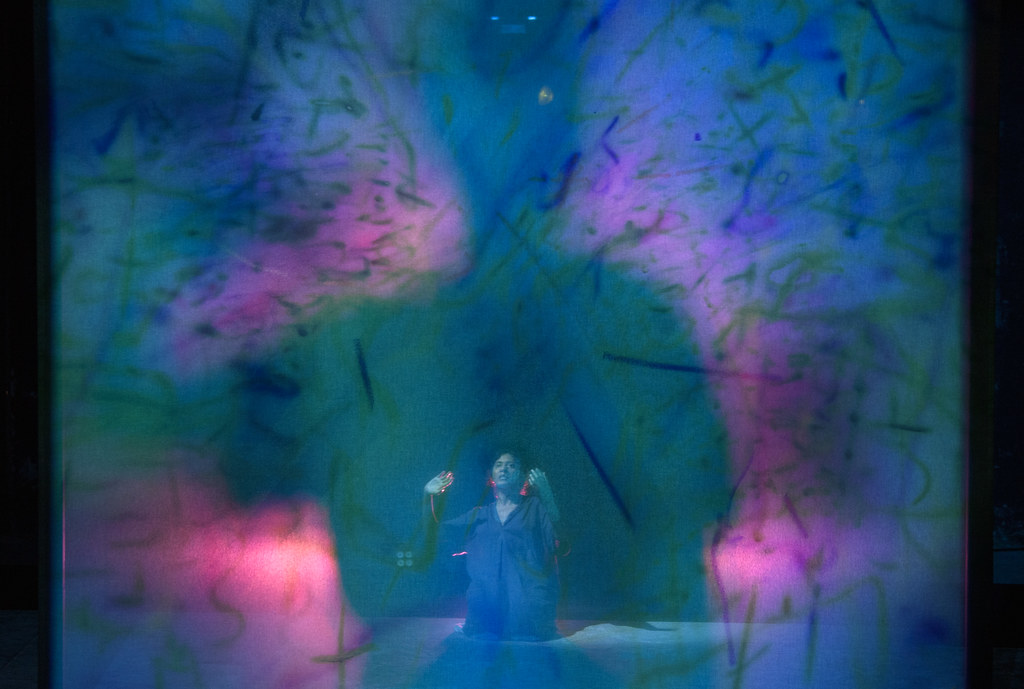

The Nine Jewelled Deer, Sivan Eldar, Ganavya Doraiswamy, Festival d’Aix-en-Provence, 2025. Photograph by Ruth Walz.

And the process for The Nine Jewelled Deer was different. You didn’t begin with a commission or a production contract. How did the creative process unfold? Did the music come first?

It began as a musical encounter. Peter already knew my work and Ganavya’s. He felt strongly that we should not follow the usual order—text first, music second—but instead let our musical worlds be the starting point, since the dialogue was already there.

So in our first workshop in Los Angeles in the summer of 2022, we arrived thinking we should prepare musical sketches. But Peter said: no music, not yet. We spent ten days simply reading, talking, and getting to know one another as collaborators. His house is essentially a vast library, and he would constantly pull books from the shelves, finding exactly the right passage. He gave me an enormous reading list, which I pursued the following year while in residence at Villa Medici in Rome.

That research ranged widely: David Shulman’s Tamil: A Biography, mystical Tamil poetry by Nammalvar, which reminded me of the Hebrew Song of Songs, June Jordan’s poetry, the Buddhist Vimalakirti Sutra. All this fed into the project, along with stories from Ganavya about her grandmother, who played the jal tarang—a nearly extinct instrument of tuned ceramic bowls filled with water, adjusted in real time during performance. Learning about that and other instruments, like the mridangam played by Rajna Swaminathan, was part of the immersion.

This was not mere research but a way of entering a world together—vast, layered, personal. Unlike a conventional opera where a librettist defines the subject, here the process was collective from the start, rooted in personal histories and discoveries.

That sounds unusual for opera. Since composition cannot be improvised on the spot, how did you manage this collective creation?

The project grew step by step. First Peter, Ganavya, and I; then Lauren; then the musicians. Each brought specific needs regarding notation and freedom.

For example, Nurit Stark, a Juilliard-trained violinist, requires a detailed score to feel free. Rajna Swaminathan, by contrast, comes from the oral tradition of South Indian percussion and is also a trained pianist and composer with a PhD from Harvard. Most Western composers simply ask her to improvise, but I wanted to learn how her instrument is written for. In the score, I indicated rhythmic patterns for her.

Ganavya’s part is notated approximately: she will interpret it differently each time, and the violinist must adjust to her phrasing. Each musician’s relationship to notation required tailored approaches. That was the research: to understand what each performer needed in order to feel free.

Some sections are fully notated; others are modular or guided improvisations. The prologue, for instance, is fixed; the prayer sung by Ganavya is open and reactive; duos may be strictly scored; ensemble scenes sometimes guided by singers. Improvisation was not a concept but a necessity arising from the diversity of traditions.

So the opera plays with storytelling itself, without a traditional libretto.

Exactly. From the outset, I conceived it as “an opera for eight soloists”—voices and instruments alike. The instruments were storytellers on equal footing with the singers.

The Nine Jewelled Deer, Sivan Eldar, Ganavya Doraiswamy, Festival d’Aix-en-Provence, 2025. Photograph by Ruth Walz.

Peter Sellars called it a “horizontal opera.”

This is key. Each performer had their moment; instruments often carried the narrative more than voices. There were no surtitles for sung texts, only for spoken passages in English, so when text was sung it was as abstract as a violin line, another layer of equality between voices and instruments. Staging followed the same principle: everyone moved, shifted roles, sometimes supporting, sometimes leading. It was a radical departure, especially for singers used to being at the forefront.

And what role did electronic music play?

I’ve worked with Augustin Muller of IRCAM since 2017, developing ways to blend acoustic and electronic sound. As with the musicians and singers, we don’t subscribe to a hierarchical model where the composer dictates and the technician executes.

In earlier projects, he was offstage, triggering precomposed sound files. For this opera, I wanted him on stage as a performer, playing electronic music in real time. He built a custom controller, allowing him to follow constantly shifting tempi, combine sound “families” I had developed over the years, and interact with the ensemble. He was playing a highly complex hybrid instrument with multiple simultaneous functions: triggering, sampling, processing, performing.

Artistically, my approach to electronics is to create hybrid “orchestras” from sound families—combinations of acoustic samples, instrumental techniques, and noninstrumental textures. The result is a polyphonic ecosystem, something both acoustic and otherworldly. With Augustin, this became a living presence on stage, as versatile and expressive as any other instrument.

And how did the Franco-American context shape the project?

The team was mixed: Augustin and Sonia Wieder-Atherton in France, several musicians in Germany, Peter, Lauren, and Ganavya in the U.S., the painter Julie Mehretu in New York. The differences in cultural infrastructure were clear. In the U.S., sustained research in the arts often depends on universities, whereas in France we have public institutions like CNRS or IRCAM that support long-term projects. Residencies offer time but not production support.

The Nine Jewelled Deer was difficult to categorize, even after its premiere. That made it challenging for a producer to back it from the outset. Instead, we relied on structures like Villa Albertine, the Camargo Foundation, IRCAM, Villa Medici, Royaumont—institutions that support exploration regardless of outcome. Peter’s method also resists defining the final product too early. He wanted us to embark on a process of discovery, trusting that only at the end would the work cohere.

Freedom seems to have been essential.

Freedom was at the heart of this project—the freedom to explore without the pressure of fitting into an existing box. To me, that is the very definition of “experimental”: you don’t know the result in advance. If you already know the answer, then it is no longer an experiment but a rhetorical exercise. The best teachers, as we know, are the ones who ask questions without knowing the answer themselves. That was precisely the spirit of The Nine Jewelled Deer: to ask questions we did not yet know how to answer, and to let the work emerge from that process.

This freedom also explains why the work was polarizing. Some people were moved to tears; others rejected it. But “experimental” should not be confused with “inaccessible.” In fact, musically speaking, this opera may be more accessible than other things I have composed. What was experimental lay elsewhere: in the form, in the decision to give instruments the same narrative weight as singers, in bringing together musicians who did not necessarily read scores, in creating a dramaturgy that placed them all on an equal plane.

Production models often demand clarity of form and marketability from the outset. But residencies offer an alternative model. They make it possible to spend years developing a work without knowing what the final form will be. Now that the piece exists, institutions in both the U.S. and Europe are determined to organize a tour.

This says a great deal. Once the work exists, it can resonate powerfully. France, with its established institutions like Villa Albertine, Camargo, Royaumont, Villa Medici, IRCAM, was the place where the freedom to experiment most radically could be sustained.

Interview by Raphaël Bourgois

Sivan Eldar is a composer. Her honors include the Fedora Opera Prize, the Prix de Rome, SACD’s New Talent Award, and Opera America’s Discovery Prize, along with residencies at MacDowell, Civitella Ranieri, the Camargo Foundation, the Cité Internationale des Arts, and Snape Maltings.

This interview first appeared in States, the annual magazine of Villa Albertine, published in January 2026.