What the Body Knows: An Interview with Wanjiru Kamuyu

Photograph by Raphaël Caputo / Metlili.net

By Wanjiru Kamuyu, choreographer, dancer, performer

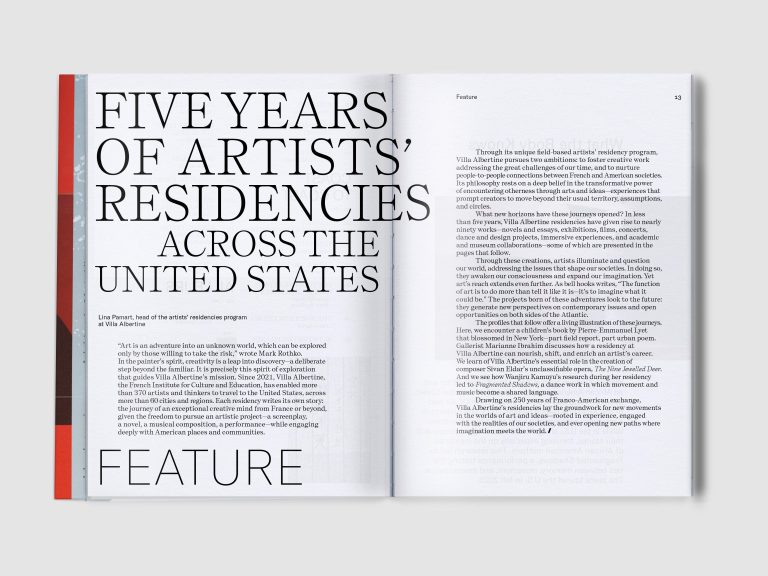

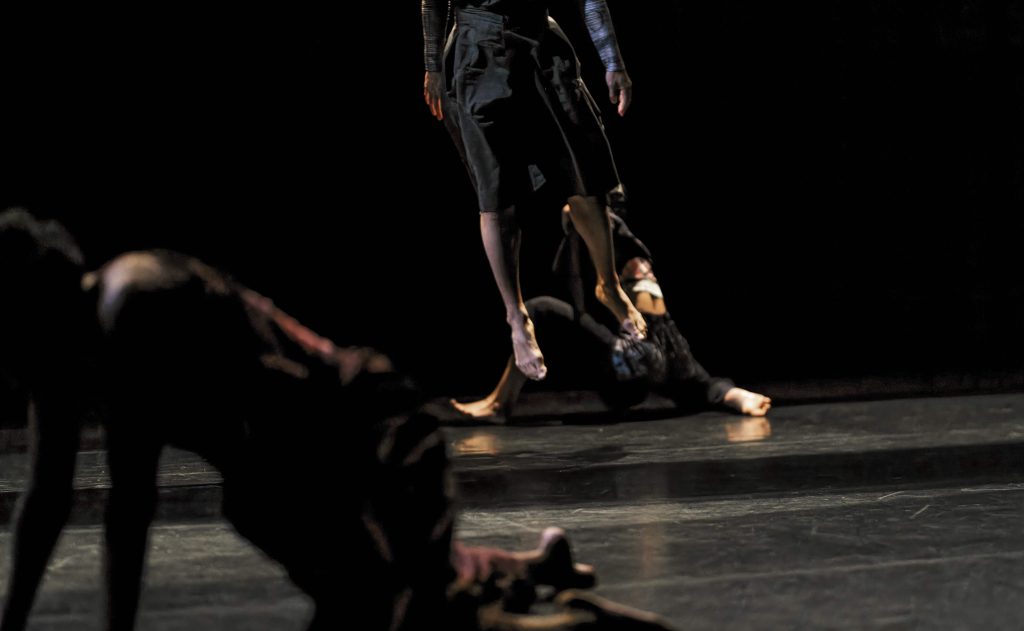

Wanjiru Kamuyu, born in Kenya to a Kenyan father and an African American mother, moved to the United States at sixteen and has lived in Paris since 2007. As part of the Albertine Dance Season 2023, she undertook a residency exploring the body as a site of liberation. While in the U.S., she gathered recordings of people and their stories, focusing especially on the memories of African Americans. This research led to Fragmented Shadows, a performance tracing the ties between memory, movement, and emancipation. The piece toured the U.S. in fall 2025.

STATES How did you come to this question of how the body retains memory of the past?

WANJIRU KAMUYU The question has always been with me. It’s always been there, even if I hadn’t consciously identified it in my work. This time, I wanted to. I remember creating An Immigrant’s Story (2020), a performance that explored the experiences of immigrants, floaters, nomads, expats—all of us. Then I began thinking about the most difficult of these stories: what becomes of the body ten years after such experiences? You’ve crossed oceans and deserts, survived the unimaginable as a refugee. How does that sit in your body?

I began exploring this at the time George Floyd was killed, and when we were all confined by Covid. It was overwhelming. People kept calling to ask if I was okay, and I was—but I would tell them: deal with the issues of race, inclusion, and healing justice work in your community. When these conversations come from within a community, they resonate differently than when they arrive from outside.

Before going on our U.S. tour, I had a conversation with choreographer Bill T. Jones. He suggested an informal preshow conversation, a space designed to give potential audience members an inside view of the work before stepping into the theater. The aim was to help people feel more prepared, and less intimidated, when encountering abstract contemporary dance. Around the same time, I was talking with Jones about the historical weight carried by the body in performance, when he said to me, “You were wounded, but you didn’t know you were wounded.” That struck me deeply. The weight of racism sits on my shoulders as a woman born and raised in Kenya—without my realizing that those shoulders are constantly tensed, up to my ears. That wound lives in the body. I wanted to create a work about release, about opening space to breathe. To explore both personal and collective healing through movement, which has long been part of my journey—this time, deliberately. I’m tired. It’s exhausting to exist in a space where one is judged by appearance, and as a woman it is a double burden. I wanted to create a space—for myself, for my dancers, for the audience—to breathe and experience something together.

When you look back at An Immigrant’s Story, would you say there’s a journey between that piece and your new work, Fragmented Shadows?

Absolutely. I collected nineteen stories for An Immigrant’s Story. I wondered how these narratives would live in our bodies over time. I believe emotion and story are stored in the body; they can create ease if they’re joyful, or disease if they’re painful. Some of the stories were deeply traumatic. I wanted to explore how such experiences linger physically and to create a work that offers a kind of therapy—a work that creates space in the body and allows for healing. This became the starting point for this new piece.

During your residency with Villa Albertine in the U.S., what was the focus of your research? This was research that led to Fragmented Shadows, I believe.

My research centered on the maternal side of my family. My mother is African American, and I wanted to explore the transgenerational transmission of memory within that lineage: descendants of people enslaved and forcibly brought to America through the transatlantic slave trade. My grandmother also told me stories of the Great Migration, of her family’s journey from Alabama to Michigan in search of work, liberty, and a space to live freely.

You also met scientists studying epigenetics. What did you learn from those encounters?

I came upon epigenetic studies and explored them as best I could, given my limited scientific background. Epigenetics examines how experiences and environments can modify gene expression—how trauma, stress, or healing can literally alter cellular behavior. I was especially interested in how this applies to African American communities, which remain understudied because of systemic racism in medicine and the communities’ understandable mistrust of medical institutions.

I went to Johns Hopkins and met with Dr. Peter Abadir and his team. We discussed aging, disease, and how environmental and psychological factors influence our cellular biology. Epigenetics is a relatively young field, about a century old, and its findings are still debated, since scientific “proof” requires decades of validation.

Other communities have been studied more closely, right?

Yes. Before visiting Johns Hopkins, I found many studies focused on Jewish communities and the Holocaust. Research shows that the trauma experienced by survivors altered gene expression, making later generations more predisposed to anxiety and post-traumatic stress. That idea of trauma inscribed in the body across generations resonates deeply. I wanted to explore it in African American communities—and perhaps one day in my Kenyan lineage as well.

My father lived through the colonial period and the Mau Mau uprising for independence. Trauma is universal, but beginning with my maternal side felt essential. One of Dr. Abadir’s colleagues mentioned that African Americans have the highest rates of asthma. Epigenetics might help explain that. I personally suspect—though this is not scientifically proven—that being confined in the holds of slave ships for weeks or months, unable to breathe freely, could have left a lasting physiological mark.

Photograph by Raphaël Caputo / Metlili.net

Your work also addresses dance as a healing process. You cite Cara Page, a Black Lives Matter activist who writes about “healing justice.” Can you elaborate on your view of dance as healing?

I asked the scientists whether they believed movement could heal, whether the body could reverse cellular damage through new habits. They said that while evidence is still emerging, stress-reducing practices like yoga or mindful movement can help the body shift toward balance. For me, movement is liberation. Healing happens through the moving body. In my process, I integrate somatic practices: breathwork, imagination, and sensorial journeys. These invite the body to release tension and find calm. Movement allows us to be present and to reconnect with ourselves.

As a choreographer, how do you translate this into your art?

Through texture, dynamics, and varied choreographic languages. It’s not simply lying on your back and breathing. The work delves into tension and release, surrender and expansion—all physical manifestations of emotional states. I drew from the five elements (fire, water, air, earth, and metal) and from words that guided me: release, float, ritual. Repetition induces a trance-like state, a space of dissolution and transformation.

I also asked the two other dancers to bring something from their own traditions—movements that carry trance or ritual energy. Élodie Paul brought Gwoka, a traditional dance from Guadeloupe rooted in music, rhythm, and collective expression; Sherwood Chen brought his Body Weather practice developed by Min Tanaka; and I brought the Ring Shout, a spiritual practice from the African American church tradition in which worshippers, in a trance-like state, move in a circle, embodying life, death, ancestors, and renewal. During such rituals, stewardesses of the church stand nearby to ensure participants’ safety as the spirit takes hold. This sense of communal protection and release is woven into the piece.

It became a melting pot, which we shaped slowly—integrating some parts, leaving others aside.

For Fragmented Shadows, you chose a nonnarrative form. Why did that feel right?

Abstraction can be challenging, especially for audiences less familiar with contemporary dance. But I wanted that, because memory itself is fragmented. Some memories are vivid, others half-forgotten; others entirely subconscious. Like life, memory is incomplete. Fragmented Shadows isn’t about explaining; it’s about experiencing.

Hence the title.

Exactly. The “shadows” refer to what is invisible, and the work is about making the invisible visible. Not only the physical body but the memories it carries. What do we confront when we face ourselves? We all keep things hidden. The piece explores acknowledgment and denial, visibility and invisibility—bringing light to what remains in the shadows, and finding shadow within what is already illuminated.

You created this work in France and will now tour in the U.S. Do you expect different reactions?

Honestly, I’m nervous. I remember presenting at the Association of Performing Arts Professionals in New York and wondering whether the city’s restless energy would allow space for stillness. Fragmented Shadows moves between slowness and intensity; it demands quiet attention. Then I saw Faye Driscoll’s Weathering, and it gave me hope. With today’s growing culture of care, perhaps slowing down is becoming acceptable.

Each context brings its own cultural dynamic. We’ll perform in North Carolina, then New York—which is its own country—and then in Ohio. I’m curious how different audiences will engage. I’m glad there will be post-show Q&As, so people can ask questions rather than leave, as Bill T. Jones once joked, “scratching their heads wondering what they just saw.”

Photograph by Raphaël Caputo / Metlili.net

Let’s talk about production. The research was supported by a Villa Albertine residency, and this tour by a FUSED grant, which is a program of Villa Albertine and the Albertine Foundation. But I imagine that’s not enough to produce such a piece.

Funding Fragmented Shadows was very difficult. And my next project is even harder, since times are tougher financially. For Fragmented Shadows, I had French coproducers: Théâtre de l’Onde in Vélizy-Villacoublay, where I was an associate artist; the CCN in Belfort and in Nantes; and private funding from Caisse des Dépôts, which came through after much stress. Villa Albertine supported the research, and Le Tangram in Normandy was a partner.

In New York, I met Janet Wong at New York Live Arts. I told her I didn’t have enough money. I had planned a quintet but was down to a trio and even considered a solo. Janet helped find a private donor who supports women artists. Okwui Okpokwasili and Peter Born, through their company Sweat Variant, also stepped in at the last minute, thanks to their Artists Supporting Artists Program (ASAP), a new effort to support fellow contemporary artists. I was part of their first ASAP cohort, and their support arrived just three weeks before the premiere. The project was also supported by Le Quartz in Brest, the French Ministry of Culture’s regional office in Île-de-France, and the Île-de-France regional government. Without all of this support, I don’t know how I would have managed.

So, it required nearly ten different sources of funding.

Yes, and it was the first time U.S. arts organizations ever funded my work. The whole creation was extremely stressful. You must pay people fairly—that’s a moral contract. So you have to face the challenges of securing funding.

It’s also an important work for you because it’s rooted in your family history.

I really wanted it to exist. It’s also my first piece with other professional dancers. I usually make solos. Here, I wanted to collaborate, to cocreate. Instead of giving dancers movement to reproduce, I invited them to excavate from within their own bodies. It was a new process for me. One dancer, an incredible improviser, had to learn to retain structure while keeping freedom—so I had to think strategically about how to balance both.

After everything you’ve described, the piece feels like a manifesto: an affirmation of the transformative and healing power of dance.

It’s my conviction. Dance is a powerful tool, though I prefer to say movement. Because “dance” can sound exclusive; people like my own father often say, “I don’t dance.” But everyone moves. Movement is a vector for healing and liberation. Fragmented Shadows is indeed a manifesto for that—for the transformative power of movement.

Interview by Raphaël Bourgois

Wanjiru Kamuyu is a Paris-based choreographer and dancer whose international collaborations and solo creations explore migration, memory, and identity.

This interview first appeared in States, the annual magazine of Villa Albertine, published in January 2026.