Between Fascination and Rivalry: 250 Years of Cultural Exchange

By Mohamed Bouabdallah, Cultural Counselor of France in the U.S. and Director of Villa Albertine

During Art Basel Paris in October 2025, I attended the opening of Echo Delay Reverb: American Art, Francophone Thought at the Palais de Tokyo. This inspiring exhibition brought together five decades of American art—by figures such as Coco Fusco, Félix González-Torres, Cindy Sherman, and my dear friend Kiki Smith—and paired these works with French texts by Simone de Beauvoir, Aimé Césaire, Frantz Fanon, Michel Foucault, and others whose ideas, improbably yet decisively, helped shape American art and thought across three generations. Display cases of journals, pamphlets, and critical essays from the 1960s to today placed this intellectual history in dialogue with the works on view. The curators described the show as a map of a “two-way flow of ideas,” and it offered a vivid illustration of the distinctiveness of Franco-American exchange—a conversation shaped by translation and reinterpretation, by moments of misalignment, and by flashes of sudden clarity.

This year marks the 250th anniversary of the American Declaration of Independence, and this issue of States takes the enduring friendship between France and the United States as its theme. The relationship is often described in diplomatic or political terms, with its (many) ups and (some) downs, but at its heart it is an ongoing act of mutual curiosity and affection. From their earliest encounters, France and the U.S. recognized something of themselves in each other—a shared belief in human possibility that gave the relationship an almost spiritual dimension. Our histories have grown intertwined ever since, each shaping the other’s understanding of democracy, culture, and identity. Across two and a half centuries, France and the U.S. have served as each other’s mirrors—always attuned to what the other reveals. It is not a story of continuity but of reinvention; each generation discovers the other anew and, in the process, rediscovers itself.

From their earliest encounters, France and the U.S. recognized something of themselves in each other—a shared belief in human possibility that gave the relationship an almost spiritual dimension.

States begins by returning to the origins of the Franco-American alliance—when the Enlightenment was still an argument, when democracy was a radical experiment, and when revolutions were living projects rather than historical narratives. Our special section, Independence at 250, opens with a conversation between Robert Darnton, an American historian of eighteenth-century France, and Carine Lounissi, a French historian of the American Revolution. Their exchange traces the intricate loop between two nations in the Age of Revolution—an intellectual traffic of books, pamphlets, and ideals that shaped both countries’ visions of democracy.

This is a story far richer than textbook summaries: a French King embracing and aiding the struggling American Republic; American pamphlets sparking revolutionary debate in Parisian salons; French clandestine literature landing on George Washington’s bookshelves. As Darnton and Lounissi explain, the first phase of the alliance quickly went under strain. After the French Revolution, American leaders grew wary of Jacobinism, while France was disappointed by U.S. neutrality in the conflict between Revolutionary France and monarchical Europe. By the end of the eighteenth century, the two republics—born of similar aspirations—found themselves in a brief naval conflict, each uncertain where admiration ended and national interest began.

As the revolutions of the eighteenth century faded into the nineteenth, the axis of exchange between the two nations shifted. If politics had early on drawn the two countries together, culture kept the conversation alive. For Americans, Paris became a laboratory of artistic experimentation—its cafés and studios hosting revolutions in painting, photography, and literature. Meanwhile, the U.S. appeared to the French as a young, vast, confident, sometimes unruly republic with an industrial might that promised a different vision of the future. The century also produced the most enduring emblem of the relationship: the Statue of Liberty, the colossal figure designed by Bartholdi and engineered by Eiffel, a gift that embodies both friendship and liberty—as universal promise and unfinished project. The ties forged in this period took on a new meaning in the twentieth century, when two world wars drew France and the U.S. together in moments of profound crisis and solidarity.

In the twentieth century, modernism itself emerged from the long, restless crossing between France and the U.S. Generations of American writers, artists, and musicians came to Paris to test themselves against what they saw as the world’s artistic crucible: Gertrude Stein, Ernest Hemingway, F. Scott Fitzgerald, and other members of the “Lost Generation”; painters such as Mary Cassatt, John Singer Sargent, and Beauford Delaney; musicians such as George Gershwin, Aaron Copland, John Cage, and Philip Glass, many shaped by the teaching of Nadia Boulanger. For Black American artists—James Baldwin, Richard Wright, Langston Hughes, Josephine Baker, Sidney Bechet, Quincy Jones, Charlie Parker—France offered a fragile but real refuge from Jim Crow, a place where jazz, literature, and political thought converged.

The war years added another chapter to this exchange: the U.S. became a refuge for French artists and intellectuals fleeing the Nazis and the Vichy regime. Anthropologist Claude Lévi-Strauss—rescued in 1941 from Marseille by Varian Fry’s network with support from the Rockefeller Foundation and other philanthropists—found in New York a place of safety and reinvention. His encounter that year with Roman Jakobson at the New School, often cited as the moment structuralism was born, illustrates how exile could become a crucible of new ideas. After the war, Lévi-Strauss became the first Cultural Counselor of France in the U.S., appointed by General de Gaulle to facilitate American engagement with French culture.

The exchange was indeed never one-way. The story of French modernism cannot be told without Americans in its streets and salons. If American modernism was forged in Montparnasse, postwar French culture was transformed by the rise of New York—by Abstract Expressionism, Black music, and American mass culture. As Nathalie Obadia details in a report for this issue, there was an earthquake in France in 1964 when painter Robert Rauschenberg won the Golden Lion at the Venice Biennale. It was clear to many that the center of gravity for modern art had shifted to New York. Paris and New York have thus taken turns as the “capital of the twentieth century,” each casting the other as both model and foil. (With the renaissance of the Parisian art scene today, we may be witnessing another shift in the balance.)

The exchange was never one-way. The story of French modernism cannot be told without Americans in its streets and salons. If American modernism was forged in Montparnasse, postwar French culture was transformed by the rise of New York

The relationship oscillates between fascination and rivalry. Rebecca Leffler’s report in States adds to the picture, showing why cinema cannot be understood without tracing the reciprocal influences of French and American filmmakers—how the New Wave reshaped Hollywood and how directors like Scorsese and Tarantino, in turn, influenced a new generation of French auteurs. As she writes, “opposites do attract, and the love affair between the two industries has lasted for generations.” You can see it as well in the strong ties between our museums, explored in a conversation in States between Laurence des Cars, director of the Louvre, and Glenn D. Lowry, who recently concluded a transformational tenure at New York’s MoMA. Behind the affinities they discuss a productive friction: two nations with markedly different visions of how culture should circulate—market-driven in the U.S., strong state support in France—continually testing the other’s assumptions.

Where does Villa Albertine fit into this story? Five years ago, the French Cultural Services in the U.S. reimagined itself as Villa Albertine, the French Institute for Culture and Education. The transformation marked a new approach to cultural diplomacy in the U.S. Villa Albertine was conceived as a nationwide cultural institution embedded in ten American cities and attuned to local communities. The new name signaled a shift from one-way cultural promotion to a model rooted in collaboration, curiosity, and listening—an invitation for France to engage the U.S. not from abroad, but from within. Today, Villa Albertine leads and supports cultural initiatives nationwide—film festivals, exhibitions, performances, debates, and professional networks spanning education, the arts, and public life—and continues to expand with new programs. At a moment when geopolitical conflict and renewed strains between the U.S. and Europe make transatlantic dialogue more vital than ever, Villa Albertine aims to be France’s most active, innovative, and future-focused platform in the U.S. We are especially proud of the major initiatives launched over the past five years.

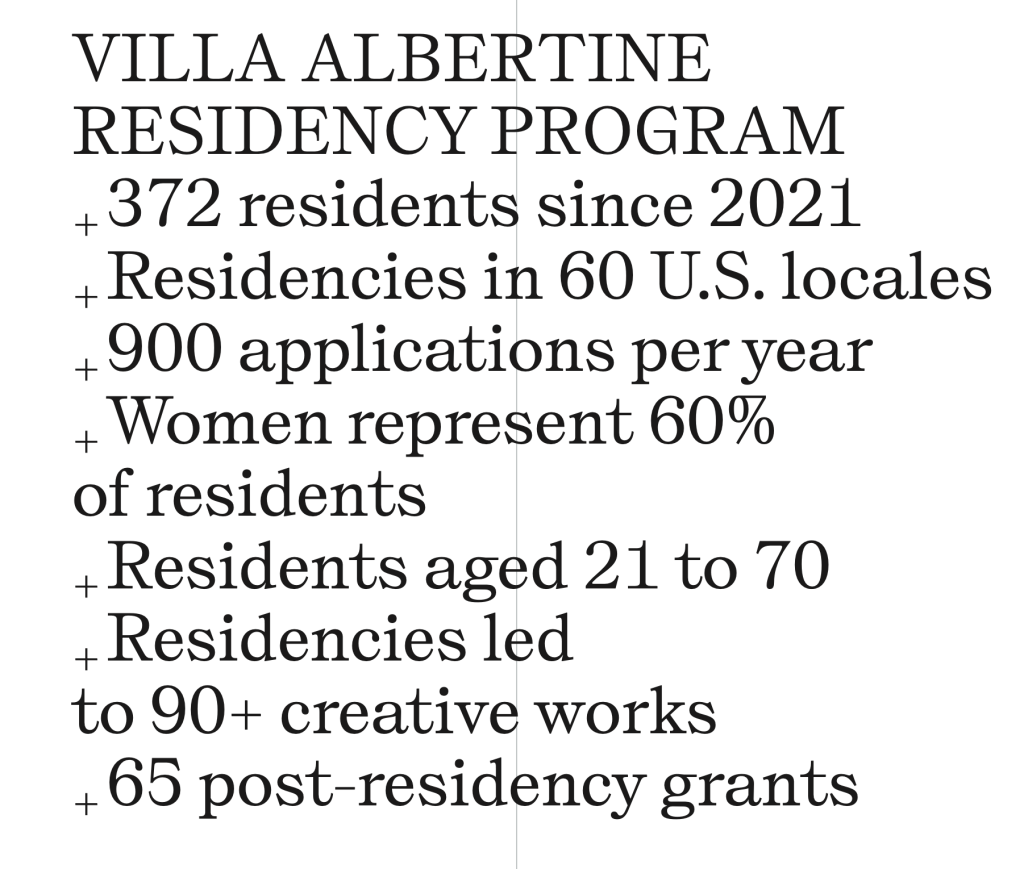

Created in 2021, Villa Albertine’s residency program supports artists, thinkers, and creators from France and the Francophone world as they draw inspiration from immersive residencies in the U.S. Every year, 60 talented creators embark on exploratory journeys throughout the U.S. as Villa Albertine residents. Chosen from among 900 annual applicants across all disciplines (visual arts, performing arts, new media, architecture, cinema, literature, and more) by an international jury, chaired by Glenn D. Lowry, our residents reflect the excellence, diversity, and dynamism of contemporary culture. With our fifth residency season in 2026, we will have hosted more than 370 residents across 60 U.S. locations, from New York to Alaska, from South Dakota to Los Angeles. This issue of States opens with profiles of partners and former residents, showcasing the deep impact and lasting outcomes of the program. In the Coast to Coast section of States, fourteen writers and artists report on recent immersive residences across the U.S.

Our French for All initiative expands access to French language education for students and communities across the U.S. Launched in 2022, it aims to make French education more inclusive by supporting public schools—especially in underserved districts—that want to create or expand French dual-language, immersion, and world-language programs. French for All is grounded in the idea that French in the U.S. is not an elite or European language, but a genuinely American one—spoken in Louisiana and carried to this country by immigrants, refugees, and heritage communities from the Caribbean, West and Central Africa, and elsewhere. It is also a global language, and young people understand this. Increasingly, students I meet want to navigate with more than one or two languages, and they continue to see French as a wayfinder in a complex world—one that opens broad regions of Africa, Europe, the Middle East, and beyond.

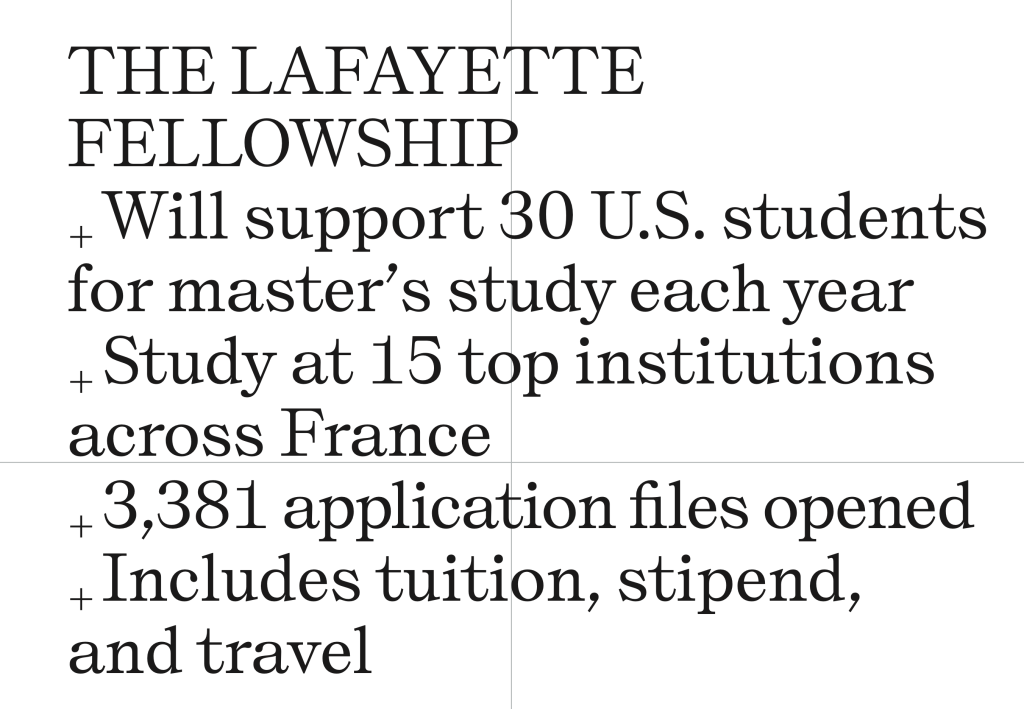

This past fall, Villa Albertine launched its newest educational initiative: the Lafayette Fellowship. Conceived as a flagship program for emerging American leaders, the fellowship is open to outstanding American students who wish to pursue graduate studies in France at top universities across all fields. Inspired by the ambition of the Marshall and Rhodes scholarships, it offers a fully funded period of research and cultural immersion designed to foster long-term intellectual exchange. At its core, the Lafayette Fellowship rests on the belief that the Franco-American relationship thrives through lived experience—through encounters with people and ideas that challenge assumptions. The program’s jury will be chaired by Nobel Prize-winning economist Esther Duflo. It will place curiosity and collaboration at its center, reaffirming Lafayette’s legacy not as a commemorative figure but as an enduring symbol of exchange, imagination, and shared democratic ideals.

In a country as large and varied as the U.S., our work is necessarily expansive. Whether through our residencies, French for All, the Lafayette Fellowship, or the hundreds of partnerships we lead each year, Villa Albertine is committed to reaching communities well beyond the cities where we are based. Our mission is built on human contact—on the belief that culture moves through people, through conversation, and through encounters that bridge distance.

States magazine is another new project by Villa Albertine, also dedicated to celebrating French-American exchange. Launched in 2023, the magazine is a French production with a global perspective, published in New York and inviting contributions from all backgrounds. It affirms a belief deeply held in France: in a world of upheaval, creators and thinkers need our support, but they also support us by helping us understand the complexities of the present moment and the challenges to come. Thank you for reading.

Mohamed Bouabdallah is Cultural Counselor of France in the U.S. and Director of Villa Albertine.

This editorial first appeared in States, the annual magazine of Villa Albertine, published in January 2026.