Objects’ Intentions: How to Make History Tangible

Robin Bourgeois

By Robin Bourgeois

“Objects are witnesses to practices linked to the history of a place or community, forming a prism through which we can question our own way of life and its archetypes.” Through the conception of daily objects, designer Robin Bourgeois works memory as a material, and brings the past into the present. Explore this three-object stroll through Lenape heritage in New York City.

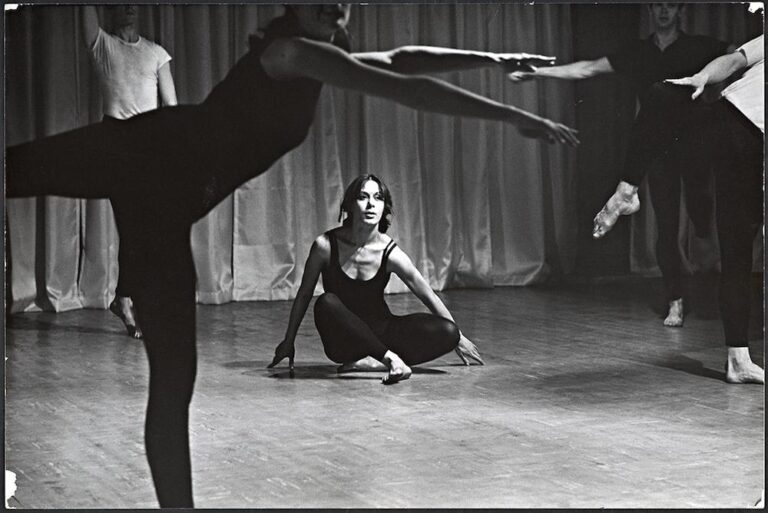

In 2018, quite by chance, I visited a Cistercian abbey in the village of Ligugé, near Poitiers, France. I don’t remember much about the historical details, but I was immediately taken by the atmosphere, the architectural elements, the objects, the monks’ garments, and the description of the rhythm of their lives. That visit made a profound impression on me and sparked my interest in the Cistercian community, so I went on to visit several other Cistercian abbeys. Some of those no longer served a religious purpose, which left me free to explore their specific shapes and spaces. I was also allowed to stay, for a few days at a time, at others that were still occupied by monks or nuns.

During my periods of immersion in the Cistercian culture, I was struck by the pragmatism and sense of the essential that characterize the life of an abbey. Those concerns (and the resulting philosophy, which obviously foreshadowed the avant-garde art movements of the twentieth century, while also seeming to provide an antidote to them) reflect the importance the monks attach to their living space, the backdrop to their daily lives. Abbey life is organized around an “architecture that is both functional and pared-down, based on a human module” (Léon Pressouyre, Le Rêve Cistercien) that focuses on the inhabitant. For the last thousand years, the Cistercians have lived with the bare minimum–not the minimum required for living, but the minimum required for inhabiting.

On my own scale and with my own means, I endeavored to interpret aspects of Cistercian thought that seemed to me to resonate with our times. I therefore proposed a collection of objects–a bench, a rug, a water set, and a breadboard–not so much to celebrate the past as to propose a contemporary reinterpretation of a common heritage.

This approach regarded the object as a witness to practices linked to the history of a place or community, forming a prism through which we could question our own way of life and its archetypes. In my view, the habits, practices, and daily lives of the past and present are opportunities to create and to explore our relationship to objects. The challenge is not so much to rediscover forgotten forms as to reuse them in a contemporary setting.

During my residency at Villa Albertine, I turned my attention to Brooklyn’s Sunset Park district, intending to create objects that would highlight local aspects, related to its daily life or to its history and that of the communities that have shaped it. I spent almost two months conducting on-site explorations that soon took me beyond the perimeter of Brooklyn. I went to some of New York’s emblematic locations, explored some out-of-the-way neighborhoods, and scrolled through online archives. I compiled a database of facts, witness accounts, archival images, and iPhone photographs.

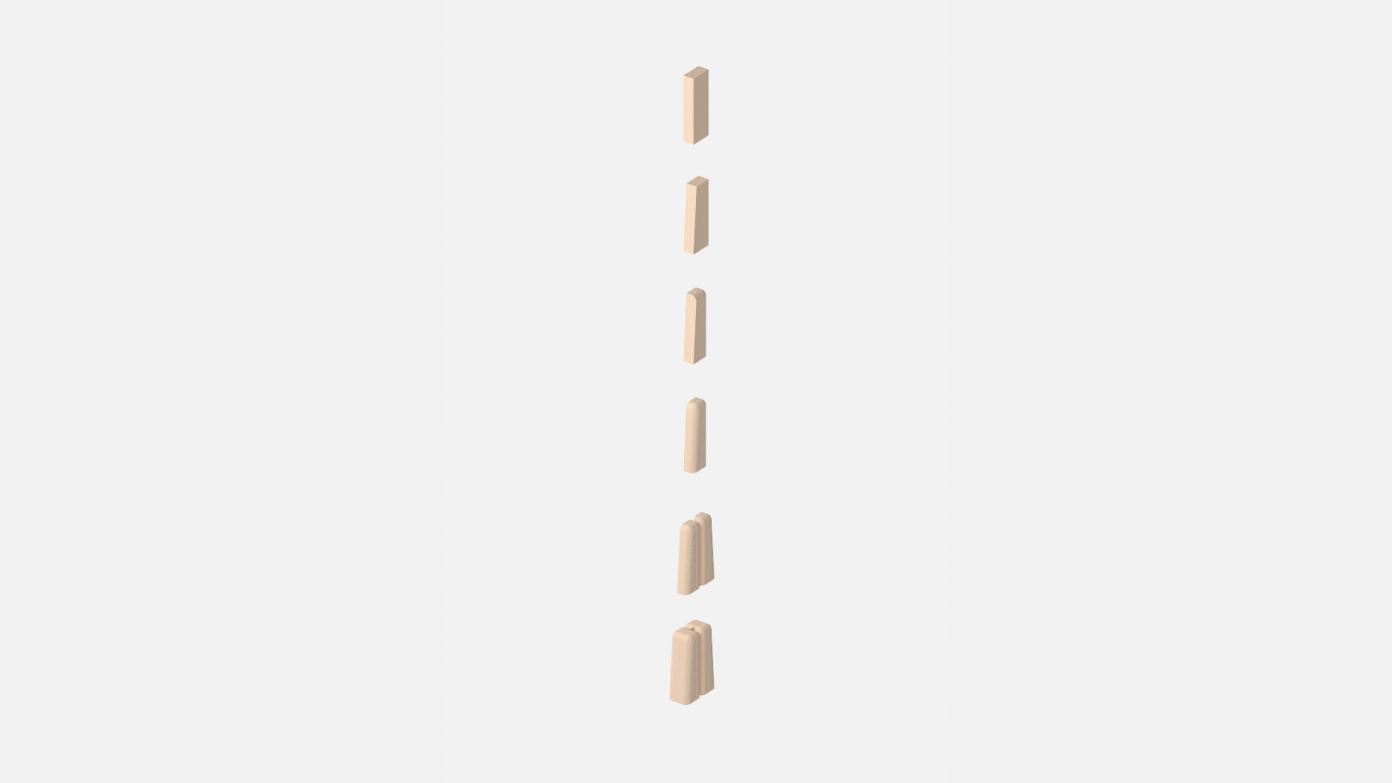

I soon came across little stories, details, and anecdotes that I considered at least as important as the official history. Those narratives became the starting point for objects that embody and celebrate them. Sketches, paper models, and quick 3D models show the objects at the conceptual stage. Although they are embryonic, these object designs attest to the research I did during my residency.

Robin Bourgeois

Robin Bourgeois

The first object whose outlines I sketched was a vase. It could be made of Virginia tulipwood (tulip poplar), which the Lenape used to build their boats. The Lenape were a Native American people; several Lenape tribes lived on the island of Mannahatta before its colonization by the Dutch in the seventeenth century. The Lenape word for tulip poplar is muxulhemenshi, “the tree from which canoes are made.”

In 1626, the Dutch “bought” Mannahatta from the Lenape living on the island, for the modern-day equivalent of 24 dollars. After the “sale,” the Lenape refused to leave; in their view of the deal, they had merely authorized the colonists to set foot on their land.

By a surprising historical coincidence, tulips were becoming extremely popular in the Netherlands at that time, leading to the so-called “Tulip Mania” that is now regarded as Europe’s first speculative bubble.

Robin Bourgeois

Robin Bourgeois

In his book Indian Givers, anthropologist Jack Weatherford has listed what the modern world owes to the Native Americans in a wide range of essential fields, including medicine, food, and politics. Many Western “discoveries” (quinine, tar, rubber, potatoes, etc.) were in fact gifts from the Native Americans to the European colonists, who made haste to pillage or destroy those discoveries together with goods, lands, and people. Weatherford shows that, despite the vast fields of application of their knowledge, the Native Americans took little interest in military techniques, which the Europeans had raised to the status of an art, particularly through their metalworking skills.

From fences to car bumpers, letterboxes, and outdoor furniture, the Sunset Park district appears to contain a metallic, chrome-plated version of every possible object. It also has many stainless steel supply stores, mostly run by Chinese immigrants. In addition to custom kitchens, they introduced the neighborhood to the chrome-plated stainless steel gates that were popular in Chinese suburbs in the 1980s.

The mirror was inspired by, and extends, that tradition, using chrome-plated steel for its inherent reflective qualities.

Robin Bourgeois

Robin Bourgeois

The candlestick is made of red clay, the material that makes up the bricks still widely used today on Brooklyn construction sites. Bricks were a luxury product in the early days of the European colonization of North America. Their rarity was not due to a lack of raw materials, but to the fact that the early colonies had few skilled artisans or dedicated factories, so the precious rectangular blocks had to be shipped across the Atlantic for use in the buildings of New Amsterdam. When I visited the Vander Ende-Onderdonk house, built in the early 1700s in Ridgewood, in what was then the countryside outlying Fort Amsterdam, I was struck by the European brick hearth, which contrasts with the stone construction of the rest of the house. The luxury of the house lies in its fireplace, hidden in the middle of the basement kitchen. This simple shift in the attribution of value was centered on function and collectivity. On its own scale, my candlestick is also an attempt to pay tribute to the bricks that shaped New York and its provinces.

My designs are a way of exploring the criteria we use to attribute value to an object, how a material can be restricted to particular functions, the mnemonic power of objects, and the universality of those symbols.

Alongside the official narrative, the stories behind each project are not linear. Some were drawn from oral sources that were not (and probably never will be) verified. Others are historical facts, reviewed from different and–more importantly–variable perspectives. The collages that connect them are arbitrary and, of course, subjective. They create oblique narratives that subtly alter certain habits.

My aim was to make those narratives and explorations tangible through forms and practices (looking at one’s reflection, arranging flower stems, lighting a room, etc.). I hope these designs will one day contribute, in turn, to the invention of everyday life.

Robin Bourgeois was in residency for the 2021-2022 season with Villa Albertine.