Why Boston?

Travel_Adventure

The Boston Tea Party, Harvard, MIT – symbols that designate Boston as a cradle of the United States, the Athens of America, and a leader in the high-tech sector. This industrial city has gradually transformed itself into a hub of scientific excellence and technological innovation, as evidenced by Route 128, which connects more than 300 businesses and labs in biology, genetics, nanotechnology, and IT. Outside of this hub, however, Boston’s weak spots of inequality and climate change are revealed.

Founded in 1630, Boston is one of the oldest cities in the United States. Buildings from the colonial era stand alongside modern towers, as demonstrated by the reflection of Trinity Church on the glass façade of the John Hancock Tower. One can follow the route of the Freedom Trail to trace the city’s role leading up to the American Revolution and War of Independence. The New World won its freedom here, and Boston proudly lays claim to this democratic ideal, as well as to the great prestige of its universities.

“In Silicon Valley, you get this feeling that you have to be out here. But it’s not the only place to be. If I were starting now, I would have stayed in Boston. Silicon Valley is a little short-term focused and that bothers me.” Mark Zuckerberg, like so many other tech titans, is a Harvard alum. From Cambridge to the city of Boston, the Athens of America, three campuses – MIT, Boston University, and Harvard – have produced between them more than 25% of all Nobel Prize winners. Boston fosters cross-cooperation on subjects as diverse as biodiversity, health, education, socio-economic inequality, and the cities of the future. On both sides of the Charles River, in Boston and Cambridge, the world of tomorrow is being created from within the city’s universities, laboratories, and businesses.

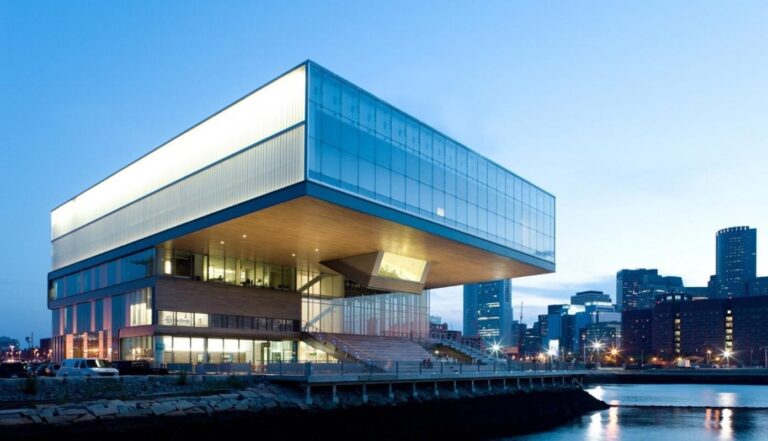

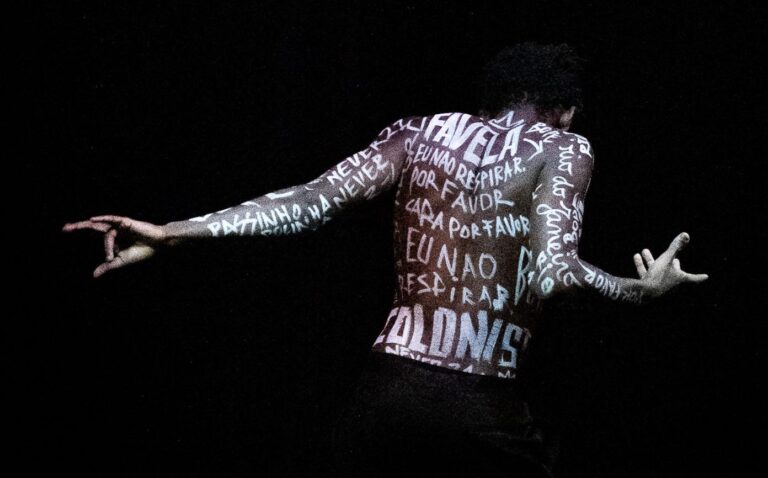

Intellectuals are equally at home here. Just as Emerson, Hawthorne, and Longfellow were once Boston luminaries, the city continues to attract people with its quality of life and artistic vibrancy, whether through its art schools (Emerson College, Berklee College), music venues (Boston Symphony Orchestra, Boston Philharmonic), museums (Museum of Fine Arts, Isabella Stewart Gardner, Institute of Contemporary Art), and festivals (Boston Film Festival, Boston Early Music Festival). Pop culture is also on the rise here, from rock music (Celtic punk band Dropkicks Murphys are from the area) to video games (Boston Pax East attracts thousands of players every year). Technological research is also applied to the arts at various MIT labs (Open Doc Lab, Media Lab) and at Boston Cyberarts.

Behind its image as a green and peaceful city, however, Boston is particularly vulnerable to rising sea levels and is one of the country’s most unequal cities in terms of per capita income and access to housing. To address the situation, Boston has committed to an ambitious progressive agenda across various issues (Imagine Boston 2030, Climate Ready Boston, Housing a Changing City, etc.) under the leadership of Michelle Wu, the city’s first elected Asian (and first female) mayor.

By setting up a base in Boston, Villa Albertine will encourage its residents to explore the crossovers between knowledge, the arts, and technology in order to solve some of today’s puzzles and help shape the world of tomorrow.