From Burgundy to Brooklyn: Eve George’s Glass Blowing Journey

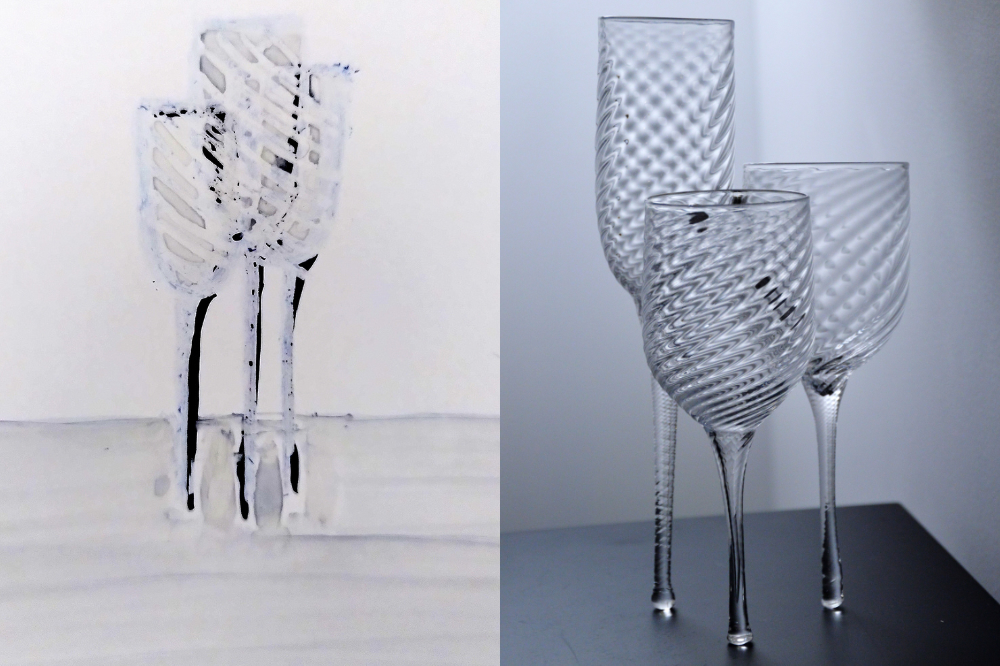

©Atelier George-Brume-Dessin de recherche & vase-Fountain

In this article, Eve George, an accomplished glass blower and designer, shares her enriching journey during her residency in New York City. Co-founder of Atelier George, Eve combines working with glass, vibrant urban experiences and varied culinary explorations. From her workshop in Burgundy’s Côte d’Or to the bustling streets of New York, food culture deeply impacted her artistic vision, ending in glass creations showcasing her evolving journey as an artist in a melting pot of cultures and creativity.

I’m a designer and glass blower and, though I have recently established my studio in Paris, my workshop, where I shape molten glass, is in Burgundy, more precisely in the Côte d’Or, a region increasingly known for its wines and traditional French gastronomy. It attracts droves of foodies and connoisseurs from afar. Among our neighbors, we have 11 different nationalities. In fact, I speak English almost as much as I do French.

When Laurent and I co-founded Atelier George, we left the Grand Est region, known as the “Glass country,” where we had trained, worked and met each other. We rebuilt a fixer-upper in the middle of the countryside and installed our kiln, some tools, and a workshop where every object conceived by our two minds is brought to life by our four hands. These special pieces are organized into collections that define a renewed artistic direction every two years.

In 2022, we unveiled “Cime” (Peak), a collection of pieces closely linked to our rural environment and partially created in the context of the COVID lockdown.

The next collection, the focus of my residency at La Villa Albertine, therefore had to both take an opposite course and extend the aesthetic close to our hearts. It was in this frame of mind that I left for New York, between February and April of 2023, to begin the groundwork for “Brume” (Mist).

©Atelier George-Collection Brume-Liquid Shot glasses

The urban situation of the American megalopolis, with its vibrant extremes, was perfect in renewing my visual inspirations.

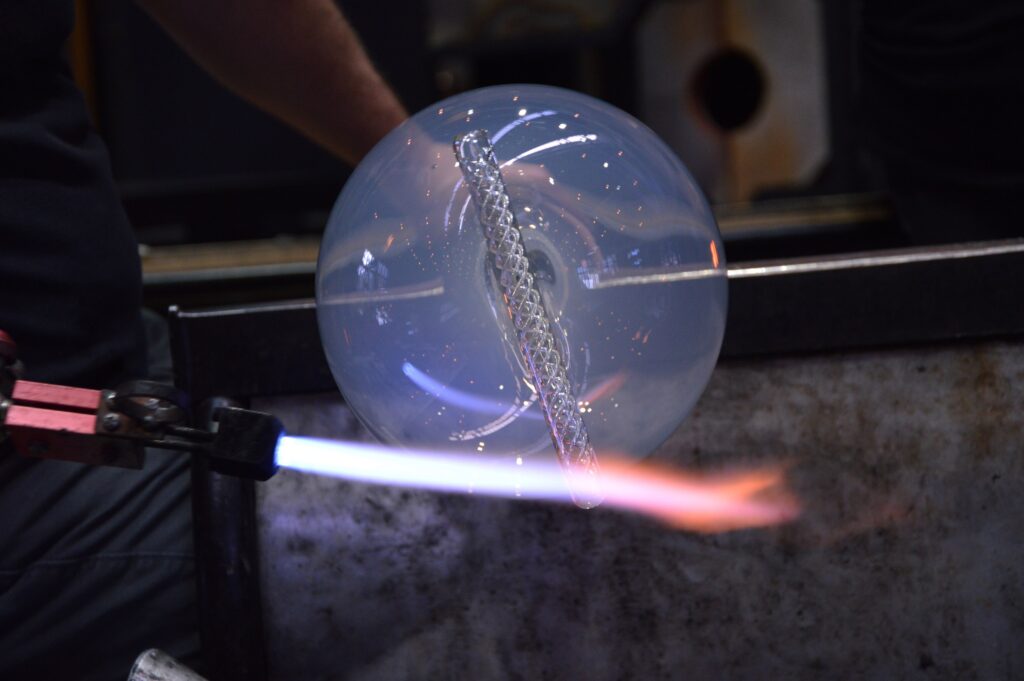

People sometimes say that I am too intense. To make light of this fact, I even have a T-shirt that says “half-measure.” Perhaps I draw this heightened freedom from my Franco-American schooling, or simply from the fact that I blow glass. Indeed, when reaching 1100˚C, glass becomes untamable. It flows, stores every gesture and movement that we bring to it, and breaks if we miscalculate the timing of the process. It’s a choreographed sequence, where the lead takes care of the burning and the partner aspires to give form to this dance, without ever taking control over the gestures and movements required.

So, we anticipate and memorize every gesture, accepting that on this dance floor the object formed will be an absolute, will have to be redone, or will simply not be. The typical determination I discovered in New York acted as a catalyst for my normal work ethic. You have to seize every instant, embrace every chance, and view each day like an opportunity. It’s both dizzying to see this productivity in action and liberating to normalize this way of life, which I have a tendency to contain or silence.

A residency allows you to dedicate time to exploration, to enjoy free discoveries, to infuse ideas with new life. It’s the first time in a long time that I have been able to take a step back, and the first time that I have officially undertaken an artistic quest, without any economic prerequisites. At least for right now.

This new freedom often clashes with the Americanization of my life in France. It’s a paradox that followed me throughout my stay.

I spent my first few days visiting numerous cultural sites and meeting my partners at the residency. Thanks to Wanted Design, I have a connection with Industry City in Brooklyn, while Villa Albertine has me gravitating toward Manhattan. In between these two worlds, I set my suitcases down in downtown Brooklyn. I moved between neighborhoods based on the people I met, unable to nail down what makes this city a whole, given such drastic changes in contexts.

A couple of days after I got there, I met Lucien Zayan, a self-made chef and founder of The Invisible Dog Art Center. I had the opportunity to attend a performance of Eva D’Oumbia’s “Autophagies,” also called “Self-Eating” by the artist. After that, we were treated to a Mafé prepared by Alexandre Bella Ola.

During the performance, guided by Eva’s words, the experiences of her troupe, and the interpretation through text, dance, music, and aromas of each ingredient that went into the dish, I became aware of the powerful symbolism that surrounds the simple fact of eating. At that moment, I decided almost impulsively to delve into the world of “Foodie” New York, aligning with the urban indecision I was experiencing.

At Industry City, a real estate attempt to build a creatively attractive and “cool” neighborhood in an industrial wasteland far from downtown, really comes together thanks to its numerous “food joints.” The Japanese Market is one of the more successful examples: a real Japanese enclave turned fast food joint, coupled with a convenience store where one neither hears nor reads a word of English. One sits at a counter and eats Ramen Noodles in disposable bowls. It’s delicious, but, it’s understood that one only comes in between 12:30 and 1PM.

The French bakery does not live up to my Parisian expectations, honed in the 12th arrondissement, but I can accept that it represents the taste of “pain au chocolat” (and not chocolate croissant) to the rest of the world.

At Barely Disfigured, a French barman gives us a paperback with the menu stuck inside. Or maybe, a bookmark with a QR code to browse the menu. I can’t quite remember, but I do know that everywhere I went I was terrified at the idea of my phone dying.

Everything you drink is typically American. But, as I would later learn, when I read William Grimes’ “Straight Up or On the Rocks: A Cultural History Of American Drink,” and after I watched “Drink Masters” on Netflix, passing as French in these places is simply a mark of impertinence.

In Brooklyn, Saraghina Caffè is a European enclave founded by Milanese people who have perfectly adapted the atmosphere of the room and the old-world menu to the “friendliness” that the clientele has come to expect.

Lucali is a piece of Italy served in its own unique flavor. When I walk around the neighborhood at night, the endless line forming at the entrance reminds me of Supreme & Apple, which, despite its name, has nothing at all to do with food. The fuss here is about Pizza, supposedly Jay-Z’s favorite.

Nura in Brooklyn reinterprets Indian accents through the prism of American nouvelle cuisine. The naans are perfect. I don’t know what traditional American cuisine would be, since what I find here is constant, sometimes frenetic, attempts that combine and appropriate cultures without any hesitation in order to renew their own. Boundaries are fluid and crossed as if one were changing channels on the TV, or swiping or clipping the endless flow of information found online.

Fish Cheeks is also the result of this cultural mashup: the chefs are originally from Thailand. I’ll just mention the Bo Lan ice cream that soothes my palate. In place of the fudge is a jellified egg yolk that sits atop a ball of ice cream, running down when cracked with a spoon.

I always take note of the objects on the table, the decorations, the gestures they provoke, the rituals they suggest, without ever imposing them.

“I definitely advise that you share a couple of courses” would be the phrase that my gastronomical experiences bring to mind here, even the most elegant ones, in which sincere hospitality and innovation make up the American “savoir vivre.”

©Atelier George-Corning Museum of Glass Residency-Air twist bowl

During this residency, I drew a lot. I often work through iterations between planned sketches and batches of glass. But in New York, everything moved very quickly, since I was able to make a prototype of my initial sketches at the Corning Museum of Glass. After only ten or so days in New York, I flew upstate for an exceptional immersion in the world of glassmaking. In the field of international glass, the Corning Museum of Glass, with its historical and contemporary glass collection, workshop, and research facilities, is world-renowned. The center has built an international reputation in the glassmaking world, most notably because of the production of numerous video content, cutting-edge glass blowing Masterclasses, and public outreach, both on site and on Netflix.

With the help of the team of glass blowers on site, a number of partially worked out prototypes began to take shape. I also took advantage of this immersion in the world of glass to explore the museum collections and the holdings of the Rakow Library, particularly the books that focused on the art of hosting, the history of decorative table art, and the ritual of meals according to periods and places.

I discovered some Italian engravings from 1750, representing tables made up to look like gardens viewed from above. The centerpiece, first made in sugar before being immortalized into porcelain throughout the following centuries, fascinates me.

In the collections of the Corning Museum of Glass, I discovered the first examples of blown glass in the Far East: they consist of miniscule vials, dating back to the end of the 18th century, which were used to hold tobacco (or opium). Expertise about glass originated in Mesopotamia, and its transmission beyond the East and West Roman Empire – the Italian Renaissance, in Venice, reaching its technical and cultural peak –gradually occurred through trade exchanges and migrations.

As their name indicates, these are “snuff bottles”.

I remember numerous gestural choreographies introducing tastings: my friend Céline Pelcé – a former resident of the Kujoyama Villa in Kyoto – had officiated a tea ceremony at the workshop before my departure and had passed on to me this taste for staging. I also think of the action of smelling the aromas of a wine before swirling it in the glass. I then conjure up a typology entirely dedicated to “scenting” and give it the form of vials filled with aromas: miniature bottles to bring to one’s nose before sampling.

©Atelier George-Corning Museum of Glass Residency-Snuff bottles

Back in New York, my suitcase full of glass samples imitating sea foam, tides, and the reflection of water, as well as several prototypes of tableware, I continued my exploration of the city.

Now, its layout looks like an immense banquet to me, where city blocks are individual placemats with roads and waterways separating each seat. In place of skyscrapers in the heart of the city, there are the tallest pieces, decorations, vases, and dishes. All around, a vast variety of shapes, carefully placed on a grid.

I imagine still lifes resembling isometric architectures, drawn with a calibrated felt pen on tracing paper, with the title, written in stencil, in a cartouche at the bottom right,

Lucien Zayan prepares a dinner entirely dedicated to garlic, its symbols, its taste, and its aroma, and he invites me to participate in the project. I show him my smelling vials. We find the idea of the ritual accompanying the use of these pieces to be quite entertaining, and Lucien invents a garlic decoction with floral and wooden notes that we will serve our guests as an introduction to the dinner.

I also arrange bouquets of alliums in my vases for the table. We taste a lot of things: smoked garlic that tastes like licorice and an aioli that Lucien wants to adjust to perfection, even if it’s already perfect. At the dinner table, the smelling vials elicit a flow of memories and anecdotes, all because of the scent and what bubbles up to the surface of our minds.

I have a meeting a couple days before my departure with Michael Anthony, the chef at Gramercy Tavern. We meet after the lunchtime service, even though they serve all afternoon long.

I arrive, announce myself, and Michael joins me and begins to apologize profusely: He has to settle an urgent matter, can I wait? Would I like something to eat while I wait? I haven’t had lunch, and they seat me at the bar. I understand better the architecture and the layout of the space: a huge room with a large window that looks out onto the street, “the tavern.” Next to me at the bar, a couple with a southern accent is eating a burger with fork and knife, and at a round table behind me, children are finishing their dessert. To my left, two young men in suits are talking with animation while finishing their coffee. In front of me, a tattooed barman is preparing shake after shake for the other end of the counter.

We speak of Paris. He set up the bar “La Felicita” when Big Mama opened it in the 13th arrondissement a few years back. Just before Covid. They bring me an appetizer made of yellow and pink beets, with citrus in the same color palette, coconut milk, flowers and a dash of salt on top. It’s beautiful. And very good. The couple to my right joins our conversation. They say I have to taste the burger. They ordered it because the table next to them was enjoying one when they came in. It’s word of mouth about taste that reigns in this place where food and hospitality are there to accommodate everyone. It’s fluid. And everyone feels welcome beyond their expectations.

©Atelier George-Villa Albertine Residence-Gramercy Tavern

A little further back in the room, the atmosphere feels more hushed; the round tables covered in white tablecloths set the tone. It’s the Dining Room, and they’ve just stopped serving. The menu is different, but the various spaces communicate, fitting nicely into each other. Behind me, there is a wood-fired oven and grill adjoining this very large double room with its alcoves.

The movements of the mixologist fascinate me. He turns the glasses like I turn mine in the workshop. Only the temperature is different. They’ve lent me the books authored by the chef and I leaf through them next to my plate. The first one describes his itinerary, his arrival at Gramercy, and the unique style he’s brought to the place. The second is all about vegetables. It reminds me of Alain Passard’s Instagram account. From the garden and into the plate in just a few steps. I think about how I will be returning to Burgundy in the spring. Getting back to the garden, the kitchen, wild garlic and asparagus in the woods.

Michael returns and suggests dessert and coffee at a table a little further on. His Pecan Brownie (I won’t say “pecan nut” to remain faithful to its official title) is lightly salted on top and served on a plate with vanilla ice cream. It’s delightfully decadent. It has no institutional gastronomic value. But at the same time, it is uniquely gastronomic.

We talk for hours. About the seasons, glass blown in the shape of cabbage leaves, vegetables in painting. Setting-up for dinner begins. Here, customers are welcomed starting at 6pm and up to 10Pm if they so choose. I visit the private dining room where one can eat just like at home, the staff sneaking in through a door leading directly to the kitchen. I end up visiting every station in the kitchen. In spite of all the hustle and bustle, it’s very relaxing. I know that I’m leaving, but we promise to see each other again.

I return to France with the urge to unpack and undo all the hems of the tablecloths I know. I am bringing back a line of shot glasses I finished that seem to melt in a silver-like iridescence. They will take their place at the table, even if perhaps it is not the custom. I still do not know how my glass city will be lived in or tamed. But I am eager to finish its planning and its construction.

Translated from French by Dylan Sheets, DePaul University