Emily in Paris – Louisiana Edition: Beyond Clichés

By Joseph Dunn

At the Bingo card of clichés, the popular Emily in Paris TV show ticks all the boxes of French stereotypes according to the Americans. On the occasion of Francophonie Month, Joseph Dunn has us follow Émilie in Louisiana. But that Émilie turns away from preconceived ideas, through a travel diary that comes back on New Orleans roots, and the languages spoken there.

Any mention of the Netflix series Emily in Paris in an online group discussion will prompt plenty of reactions as to the stereotypes and clichés it conveys about the French, or rather the Parisians. They’re all there: the Eiffel Tower, fashion, cigarettes, wine, extramarital affairs, contempt for Americans, and so on. But the scenes of Paris are so enchanting that it makes you dream of being part of that fantasy world of haute cuisine, eccentric chateau owners, rich and beautiful people… A whole Bingo card of clichés!

So let’s imagine a series called Emilie in Louisiana, in which a young French woman has to find images and slogans to create an advertising campaign for the Pelican State. But our Emilie will have to refrain from the usual clichés, such as the word cocodries —the Louisiana French word for “alligator”— street signs in French, French immersion classes, and T-shirts printed with the Cajun phrase “Laissez les bon temps rouler.” —without an “s” to “bons”, obviously.

She won’t go to a French Table or talk about how few of the inhabitants still speak “the language of Molière”; she won’t say the English word ‘Cajun’ instead of ‘Acadian’; there won’t be clips of elderly people describing how they were punished at school for speaking French, or of young fiddlers on festival stages.

None of all that. Our Emilie will try to communicate what lies beneath the stereotypes and clichés that the English-speaking American perspective has long associated with the people of Louisiana. She will discover the complexity of a mosaic of French- and Creole-speaking communities that is far more interesting than most of the reports and articles on the subject.

What follows is a suggested order of shooting.

Scene 1: A grocery store in Metairie, a suburb of New Orleans

Emilie follows a father and his daughter around a grocery store. They fill their basket, and wait in line at the checkout. The cashier is surprised to hear them speaking French and assumes they are immigrants or tourists. She asks them in English how long they’ve been there, and the girl answers (also in English), “Since the early eighteenth century.”

A hundred years after a new constitution was adopted, imposing English as the only language to be used in Louisiana schools, the cashier’s surprise is by no means unusual, despite the irony of the exchange that ends with, “Thank you for shopping at Robért’s,” pronouncing the last word French-style.

Scene 2: An art gallery in downtown New Orleans

During an evening spent at art show previews, Emilie meets a White artist, his Black cousin, and several other friends and guests, all in their thirties and forties. They discuss the exhibitions in Kouri-Vini, attracting the curiosity of the Americans. Emilie is convinced they are speaking Haitian Creole, until one of them explains that it’s actually Louisiana Creole, which has been spoken since the mid-eighteenth century and is a mix of the African languages spoken by slaves and the various non-standard French vernaculars in existence at the time. It’s pure Louisianan.

Scene 3: A village southwest of New Orleans

Way down the bayou, Emilie meets a Native American activist. Since the passage of Hurricane Ida, in August 2021, she has been organizing, delegating, and managing teams of volunteers, in English. But when she speaks to Emilie, she reverts to a richly-textured French, steeped in centuries of a marshland life in which earth and water come together in shimmering meadows, once dotted with oak trees.

Scene 4: A national park in Natchitoches Parish

Emilie has an appointment with a park ranger. As he shows her around the former cotton plantation, they talk about the role of the French colonists, the Creole-speaking slaves, and how they depended on the Native Americans’ knowledge to survive. She learns that the European colonists transcribed the names of the tribes in French, giving a written form to Natchitoches, Opelousas, Tchoupitoulas, Avoyelles et Atakapas, and many more besides. Emilie walks in the nearby forest, collecting sassafras leaves to make a gombo filé – the only cliché allowed.

Scene 5: A production studio in Lafayette

A young media entrepreneur – a Creole of African descent, whose family name is of Acadian origin – agrees to meet Emilie in his studio. Using images and cinematography, they explore the contradictions related to the notions of race, segregation, and the championing of the French language. Emilie discovers a parallel world, unknown to the Americanized English-speaking inhabitants of Louisiana. In that other world, racialized Creole and Cajun identity labels are often not synonymous with the language spoken and do not correspond with the definitions imagined elsewhere.

Scene 6: A balcony in the French Quarter

In July, after a torrential avalasse (summer downpour), Emilie sits on a balcony in the French Quarter, discussing a movie about a Louisiana French superhero. The main character, played by a fairly well-known musician, clowns around and dresses strangely. You heard that right–a Louisiana superhero who speaks French! Down with clichés!

Scene 7: An archive

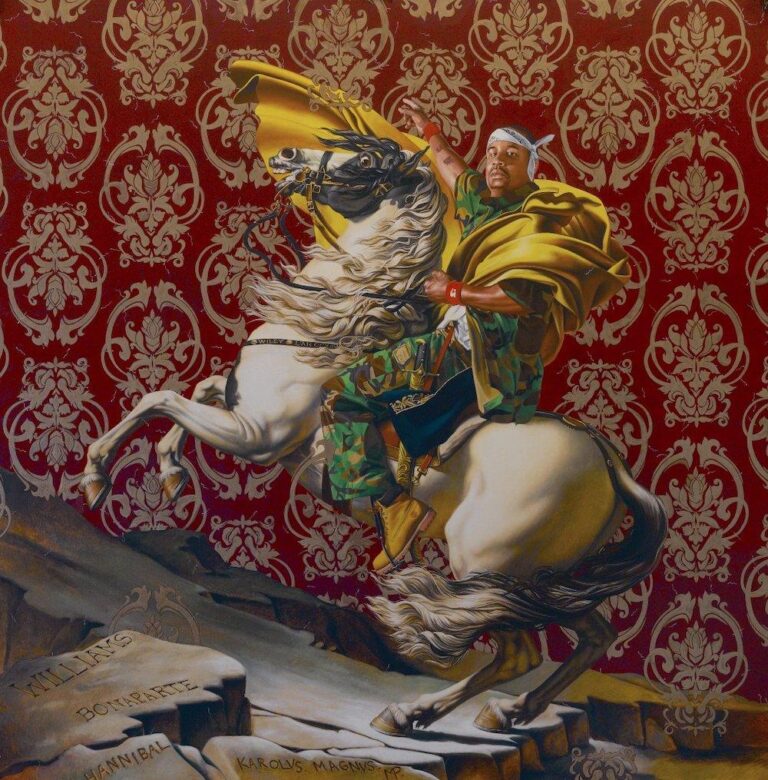

Emilie meets a researcher who is tracing the identity of an enslaved teenage boy. The boy’s image has recently been uncovered in a nineteenth-century painting (Four Children in a Louisiana Landscape by Trevor Thomas Fowler), after being completely obscured to hide his presence among white children who may have been his biological brothers and sisters. The boy’s face shows Emilie how everything we are taught about Louisiana has always been intended to conceal the African presence and influence on its cultural history.

Scene 8: Back in Paris

Brimming with enthusiasm as she shares the anecdotes and images of her extraordinary discoveries with her advertising agency’s editor-in-chief, Emilie submits her first draft. The elegant Chanel-suited editor reads the text, the Eiffel Tower visible behind her through the window, and informs her that the script must be completely rewritten: the agency’s clients want cocodries after all…

As a Franco-Louisianan, Joseph Dunn dedicates himself to cultural development and international relations in Louisiana. He was in charge of cultural industries at the Consulate General of France in New Orleans, before joining COFODIL, the Council for the Development of French in Louisiana.