Yvonne Rainer: Portrait of a Dancer as a Reader

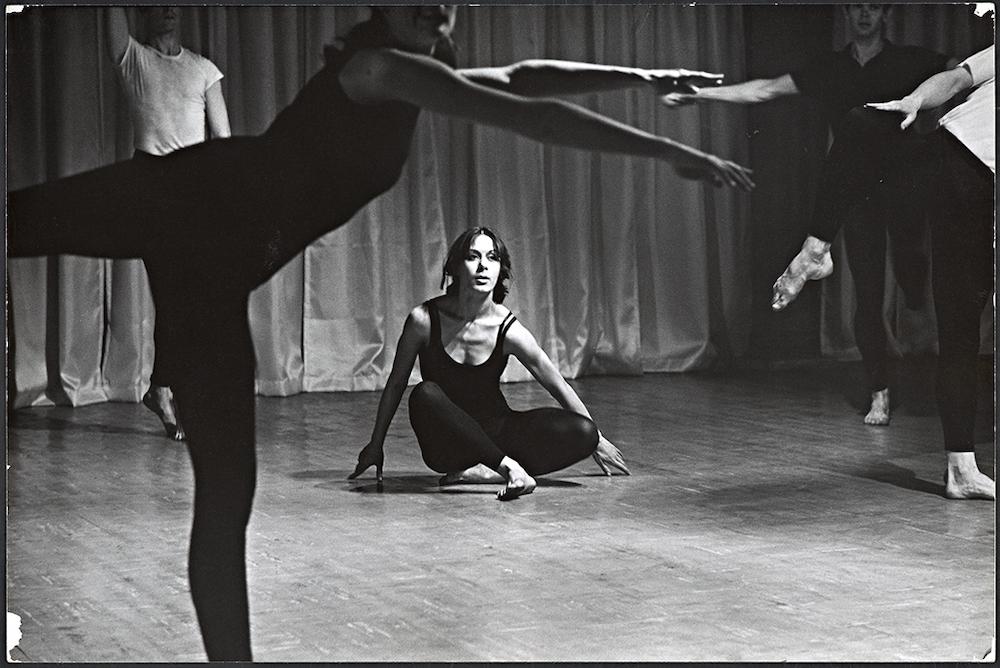

Yvonne Rainer at rehearsal for Parts of Some Sextets (1965), Yvonne Rainer. New York, 1965. Photo: Al Giese. The Getty Research Institute

By Jo-ey Tang

How to read, see and exhibit Yvonne Rainer’s work today? This was the question at the heart of Arlène Berceliot Courtin’s residency. In this interview with Jo-ey Tang, she discusses the legacy of the iconic American dancer and choreographer, a leading figure in postmodern and minimalist dance.

Arlène, you move seamlessly from one to role to the other, whether as a curator, a researcher, or a critic. Could you tell us how you inhabit these modalities? Do you know which role you occupy at any moment in time, or is the negotiating more complex and fluid?

I would say that it is at once complex and fluid. First and foremost, my role is that of a researcher. The writing of texts and interviews, as well as curating exhibitions, involves doing research. Curating is a way, among others, of bringing research to the public and initiating a collective discussion with artists, art workers, and a broader general audience. Though I conduct research at universities, I don’t work within an academic context. To me, research is an autonomous practice with its own vocabulary.

You are a 2022 CNAP x Villa Albertine laureate. Can you tell us about the context and the subject of your research here in San Francisco?

This year, the Centre National des Arts Plastiques (CNAP) and Villa Albertine initiated a partnership to support professional art residencies in the U.S. I am very grateful to be among the first laureates. My research is a long-term exploration of American choreographer, dancer, and filmmaker Yvonne Rainer. She was born in San Francisco in the early 1930s and she’s a major figure in North American postmodern dance and experimental cinema. My residency and research will strive to highlight the influence of French writings on Yvonne’s life as an artist, focusing on her interpretation and appropriation of these texts, from the 1970s to the 1990s.

Your research has taken you to New York, Los Angeles, and San Francisco. How does the Bay Area figure into your residency?

Yvonne Rainer left the Bay Area for New York in the mid-1950s. Her main objective was to study theater and to become an actress. She then decided to devote herself to dance, studying under Martha Graham and Merce Cunningham. Her childhood in San Francisco and exile from that city informed her work and her early years as an artist. This is my first time in the Bay Area. Even though today’s San Francisco is a far cry from what it was in the 1950s, to be able to walk in and explore her hometown, which is so fundamental in the history of LGBTQIA+ communities, was crucial for me. Although many of the historical LGBTQIA+ locations have closed, the city itself is an archive. I have access to the GLBT Historical Society Museum’s archive, which is one of the oldest institutions collecting personal and collective histories pertaining to these communities.

Your project bridges the geography of the U.S., as you travel from the East Coast to the West Coast, from New York to California, from Los Angeles to San Francisco. These movements are intrinsically connected to the history of dance in this country. We walked earlier past 321 Divisadero Street, which used to house postmodern dance pioneer Anna Halprin’s San Francisco Dancers Workshop. There is a “For Sale” sign on the building now. Archival photos of the Workshop show amazing communal gatherings, where bodies dreamt and lived in movements. Could you tell us more about this legendary site, and about Anna Halprin’s connection to Yvonne Rainer?

Postmodern dance and American art history are motivated by the interrelation and opposition between the East and West Coasts. Anna Halprin was probably one of the first key players of the New York choreographic avant-garde scene to uproot her practice to the Bay Area. In many ways, she was a central figure in Yvonne Rainer’s deconstruction of dance, and in Simone Forti’s and Robert Morris’s performance practice. Rainer attended her first dance workshop in the summer of 1960, having been invited by Simone Forti, who was then married to Robert Morris. This experiment was fundamental in Rainer’s development and commitment to seeking alternate ways of moving, dancing, elaborating, and writing movements.

The Bay Area atmosphere, framed by free access to the beach and the mountains, changes the rhythm of dance. In a way, the San Francisco Dancers Workshop was like a new kind of dance hall, where Halprin replaced the traditional mirrors with trees and branches. In the early 1950s, her husband, the environmentalist and architect Lawrence Halprin, designed an outdoor dance deck among the redwoods in Kentfield, in Marin County, California. For all these reasons, this place and the Dance Deck in Kentfield are crucial elements in the history of postmodern dance and the thread runs from the modern and pre-postmodern choreographers right through to the Judson Dance Theater. For instance, we know Merce Cunningham performed there. By living and working collectively during workshops, Halprin put our emotions and affects as starting points to think, live and move differently.

My visit to her archive confirmed this and spurred me to improve my knowledge of her creative process in California. Indeed, her papers offer plenty of information, whether it’s her notebooks, programs, or letters to workshop participants over the years, her personal notes where she puts forth a new vision of dance, in which nature played a central role, or black and white photographs picturing Yvonne performing at her workshops in the summer of 1960, along with key players in 20th century dance, performance, and art history, such as Simone Forti, Robert Morris, and Trisha Brown.

Your area of research spans two decades, from the end of the 1970s to the end of the 1990s. We can see this as another “movement” of time that you are considering. How fundamental is this time period, the final twenty years of the 20th century, for your work? How do you understand the social and cultural shifts from that era, in relation to Yvonne Rainer? What histories do you wish to highlight through your research?

The early years of the 1970s mark the second wave of feminism in France, soon to arrive in the U.S. It also corresponds to the apparition of the so-called ‘French feminism,’ a fake concept launched by American universities to bring back students to their campuses, after they deserted them to protest against the American military occupation in South Asia. At that period, Yvonne Rainer motivated her move from dance to cinema. She has often said that producing films was her way of expressing her emotional life on screen and on stage, which she felt was not possible through dance (either as a choreographer or as a dancer performing for others). Indeed, she began her filmmaking career with a collaboration with French/American artist Babette Mangolte, Lives of Performers, which was released in 1972. This singular film provides an exhaustive investigation of the performer’s subjectivity, combining rehearsals with performances of a dance, overlapping gestures, emotions, and affects from the past and present.

This move from bodies on stage to performers moving in front of the camera was completely new. It introduced a conceptual exploration of spectatorship, and an investigation of the narrative potential in filmmaking. In fact, Rainer’s rich and complex filmography from the early 1970s to the beginning of the 1990s contains the first cinematographic depiction of illness, aging, menopause, and consequences of the AIDS Crisis on the LGBTQI+ community in New York City, from a feminist and then lesbian perspective, and offers an individual and collective political investigation in a pre-queer period.

Throughout her career as a performer and filmmaker, Rainer has been able to constantly reinterpret her position as an artist, a female, and a lesbian. She is an example of longevity and constant reinvention, through her experience of separation, reconciliation, and commitment. Even today, she looks to the future rather than the past by working on her last dance, which questions the markers of systemic and endemic racism in the United States.

Tell us more about the concept of French feminism. What is it exactly? What differences and similarities are there with other forms of feminism? And what is Monique Wittig’s role in it?

French feminism is both an American academic designation and an editorial phenomenon from the 1970s and 1980s, which gathered together disparate essays by feminist writers and scholars from France, with little regard for content or context. This was similar to the so-called New French Novel and French theory, concepts that were in vogue at the time in the United States. French feminism gathers irreconcilable opinions through alien literary objects, such as anthologies collecting essays by Simone de Beauvoir, Luce Irigaray, Hélène Cixous, and Julia Kristeva, along with the radical and materialist feminism advocated by Monique Wittig. This amalgam, which was based on their common French origins, reveals a deep misunderstanding of Monique Wittig’s role and involvement in Feminism in France and of the reasons behind her exile to the U.S. in the mid-1970s. It is fascinating to investigate what this misunderstanding reveals about feminism. In recent years, renewed attention has been brought to Wittig’s legacy. It is time to re-acknowledge her work, both in and out of the academic context.

Your research comprises a wide range of materials, including artworks in film and performance, oral histories, and institutional archives in the U.S. What role do archives play in your curatorial process? How do you articulate and use these diverse materials? Does it necessarily translate into an exhibition of visual art and performance art? Let us start with the name of your exhibition, “Yvonne Rainer–A Reader.” Typically, a ‘reader’ is either a book, a compendium of knowledge, or a person in the act of reading. With that title, you also conjure a beautiful pivot between stillness and movement, between the act of reading (where one stays stills but with their eyes in constant movement) and the act of dancing (where ones moves in between moments of stillness).

Thank you, Jo-ey, for mentioning this ongoing project. Indeed, I would love to bring the North American concept of ‘reader’ to a curatorial form. As you know, I consider reading as part of the creative process. But we too often ignore the artist as a reader by not paying attention to the self-education inherent in reading. Regarding this point, Rainer is a splendid example of emancipation through reading. Her notebooks, now archived at The Getty Research Institute, attest to her position as a reader, questioning the meanings of dance and film, and how to relate to these practices from a feminist perspective. This is why I would like to focus my project around the archive as a protagonist, a living body, a speaking body, so to speak. The archive speaks very loudly; one cannot turn a deaf ear to these voices from the past. It is the ultimate resource. It is a blank slate, before interpretation takes hold of it.

In what way would you like this exhibition to be a celebration of Yvonne Rainer’s life and work?

I wish to celebrate her life and work as an example of constant evolution and revolution, in the context of various political movements from the 1970s to mid-1990s, and to acknowledge her as a pre-queer artist. We should read and learn from her criticism of minimalism, post-modernism, and essentialism in feminism, and also from her cinematographic exploration of aging. This is really all we should be teaching and learning in art education in France: How to become old? How to age individually and collectively?

Before we get to see “Yvonne Rainer–A Reader,” what else could we expect from you in the near future?

I recently conducted an interview with the American visual artist Nick Mauss, which was just published in Mirà, the annual magazine of Monaco’s New National Museum. It focuses on his experience working on a new creation of Yvonne Rainer’s 1965 dance Parts of Some Sextets, in collaboration with Emily Coates, for the Performa Biennial in New York City, in 2019. It was wonderful to go over this re-creation process with him and, more specifically, to explore the way Yvonne and Emily included archival as well as iconographic sources into this collective endeavor, and how the original concept challenged the re-creation. What does it mean to re-write, re-create or re-enact a dance more than 50 years after it was conceived, and in the political context of Trump’s presidency? I am also preparing, for this new year, a book project in collaboration with JRP-Ringier bringing together for the first time a collection of texts written by Yvonne Rainer from the 1960s to today, the majority of which are largely unpublished in French.

Jo-ey Tang is an artist and curator living in San Francisco. He is Director of KADIST San Francisco, and former curator at Palais de Tokyo, Paris. He grew up in Hong Kong and Oakland, California.

Arlène Berceliot-Courtin is a curator, researcher, and independent writer involved in the IKT, CEA, AICA and ACD professional networks. In 2018, after spending ten years at the head of world-famous contemporary art galleries, she co-founded the curator-run space furiosa, a project devoted to research on art and curating. Since 2011, she has been working with cultural sites and institutes, including the Centre national de la Danse, the Institut national d’histoire de l’art, Air de Paris, Galerie des Galeries, Artorama, the Bureau des arts plastiques, Gallery Weekend Berlin, and Manifesta in Marseille.