Hollywood and the French Riviera – Revival of the French-American Connection

Private collection

By Guillaume Kervern

Hollywood and the French Riviera share a common history, the invention of the film industry in the early 20th century. This history is based on an artistic and industrial avant-gardism that has long nourished exchanges, and appears to be reinventing itself today.

There is an orientation table at #7701 of iconic Mulholland Drive, in Los Angeles, that details the features of the stunning, sprawling vista of the San Fernando Valley. It tells of how, in 1912, US entrepreneur Carl Laemmle bought a 200-acre chicken ranch to launch his film production company. For a mere 25 cents, patrons could attend film shoots and visit Universal City, the first-ever city dedicated to the movie industry.

Meanwhile, Charles Pathé and Léon Gaumont, the pioneers of French cinema, were settling down in Nice, on the French Riviera. In 1905, within the walls of a former soapworks, Pathé opened its glazed “shooting theater,” to compensate for the limited natural light of Parisian studios and allow for steady, uninterrupted production. Spurred on by its competitor’s successes, Gaumont acquired its own plot in 1913, and set up the Ateliers de Nice des Établissements Gaumont. As in California, the Côte d’Azur already had its fair share of moviegoers. From the late 19th century, even before the opening of the first silver screens, theaters and casinos in Nice provided film viewings to entertainment-hungry audiences.

In addition to their tremendous topographic diversity and spectacular lighting, both Hollywood and the French Riviera, these two cradles of cinema, built their artistic vision upon a genuine industrial avant-garde concept while constantly interacting with, and inspiring, each other. How is this transatlantic dialog being reinterpreted today, and in what ways does the Riviera continue to be a vibrant creative hub for Hollywood productions?

Instant connection – Hollywood and the Riviera from the dawn of cinema

In 1896, the very first cinematic images were captured on the French Riviera, including a depiction of the Nice Carnival and one of the first traveling shots in history, taken of the Promenade des Anglais in Nice, as viewed from the sea. Hollywood filmmakers were soon enticed by the beauty of the Mediterranean, although it would take some time before the first American films were produced there–for his film Foolish Wives (1921), Erich von Stroheim instead opted to build a colossal set of the Monte Carlo Casino on the back lot at Universal Studios.

It was only in 1924 that the first major exchanges opened up between these two laboratories of cinema. After Hollywood director and MGM kingpin Rex Ingram arrived on the Riviera, the local movie industry began to grow rapidly. Fascinated by the region’s charm, Ingram took over Victorine Studios, set up five years previously by Serge Sandberg and Louis Nalpas. He moved in with his actors and technicians, streamlined the management, and shot five blockbusters, turning the site into a first-rate audiovisual production center and upgrading its equipment for the transition to the talkies.

Of course, beyond in-studio production, the natural landscapes of southern France provided an ideal backdrop for American productions. For To Catch a Thief (1954), Alfred Hitchcock had Cary Grant and Grace Kelly speeding along in a blue convertible from La Croisette in Cannes all the way to Monaco, passing by the Nice Flower Market and Negresco Hotel, Saint-Jeannet, the Nice hinterland, and the spectacular cliff roads. The storybook town of Villefranche-sur-Mer has also been a favorite among US filmmakers (in May 2021, the producers of Netflix’s Emily in Paris announced that they would shoot part of the second season of their hit TV show there).

Movie mania is another shared characteristic of Californian and Mediterranean culture. With its mild climate, the Riviera is a perennial haven for both winter and summer moviegoers, and once reached record numbers of movie theaters. Nice, for example, went from 16 theaters in 1924 to a whopping 37 in 1968! Across the Atlantic, the greater Los Angeles area (nearly 9% of the national box office) continues to outstrip the New York area (7.4%) as the biggest market for theatrical film screenings in the US.

When Hollywood reinvents the Riviera

Rex Ingram’s move to Nice should not be looked at as an industrial outsourcing effort, and even less so as Hollywood’s takeover of the Riviera. Ingram remained strongly independent from the American industry, establishing a firm anchor in his adoptive region to create his own authentic storytelling, the best example of which is probably the film Mare Nostrum. Ironically, however, the movie was not shot in a natural setting, but in the darkness of the studio. Making use of his brand-new holiday resort, Ingram built his fresh, personal Mediterranean vision from scratch, with his creativity fed by mystic and Eastern influences, and by local artist collaborations, notably with the great French painter Henri Matisse, who moved to Nice in 1916.

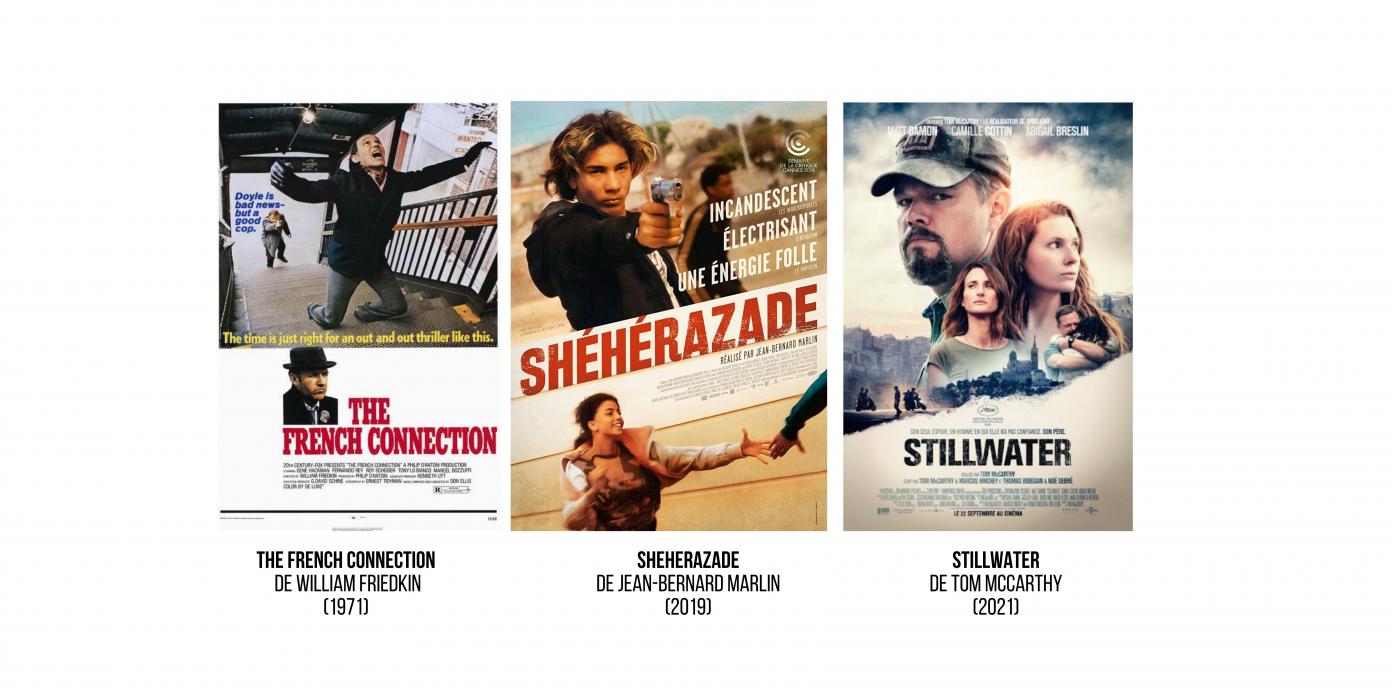

Today, Hollywood is renewing its vision of the south of France, with Marseille clearly set to be a prime testing ground. Of course, American curiosity in the region is hardly new, but its focus has mainly been on the issues of petty crime and drug trafficking–think William Friedkin’s multi-Academy Award-winning The French Connection (1971), which was shot in New York City, Washington, DC, Marseille, and Cassis, wherein Marseille itself plays a key role. Jean-Bernard Marlin’s Shéhérazade (2018) is another notable work that looks at juvenile delinquency in Marseille. The French filmmaker’s documentary fiction received high praise from Hollywood critics following its showing at the Directors’ Fortnight in Cannes and is now available on Netflix in the US.

In 2020, Academy Award-winning director Tom McCarthy (Best Picture for Spotlight in 2016) brought Marseille to the fore again with Stillwater, which celebrates the Franco-American connection in every aspect, down to the casting (Matt Damon et Camille Cottin), and offers American eyes a renewed vision of modern French realities. The director made the city his focal point, in the hopes of depicting its cosmopolitanism, haphazardness, rich cultural landscape, and the social challenges that plague it. The film demonstrates Hollywood’s desire to broaden its range of story settings and update the narrative around the now vital issue of diversity. In this respect, Marseille offers a perfect case study for exploring the complexity of territories.

From Nice to Marseille – A vibrant French movie industry attracts American directors

Hollywood creators have always seen the Riviera as a nexus of inspiration for film production. The Academy once bestowed its Oscar for Best Foreign Language Film to François Truffaut’s Day for Night (1974), adding to the film’s magnificent tribute to Victorine Studios, whose retro atmosphere permeated right through to the dressing room sets.

Decades earlier, Rex Ingram had helped position the Victorine Studios as a leading authority in constructing giant sets, including the Parisian square that was built for British film The Madwoman of Chaillot (1969) and was long used to promote Victorine to American counterparts. Tax advantages and lower labor costs were other strong criteria for its appeal. As a result, between 1950 and 2000, Victorine was able to play host to around one major American production per year.

A few lesser-known stories are nonetheless noteworthy in the history of cinema and the Hollywood-Riviera connection, such as that of the Nice-born Henri Chrétien (1879-1956), an astronomer and a prolific inventor in the field of optics. In 1927, he patented the Hypergonar lens, an anamorphic device for capturing and projecting panoramic images. However, due to the advent of the talkies, his groundbreaking invention was only rediscovered twenty-five years later, with the advent of television, at a time when film producers were seeking out ways to lure audiences back into movie theaters.

In 1953, Spyros Skouras, then-president of 20th Century Fox, met with Chrétien in Nice to sign a contract for manufacturing and operating the Hypergonar lens. The first film shot in CinemaScope was released a few months later in Hollywood and in Paris, and Chrétien received an Oscar from the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences in Los Angeles the following year. Then aged 75, he chose not to travel to California, so Olivia de Havilland presented him with the award at the Cannes Film Festival instead.

Private collection

Spyros Skouras, President of 20th Century Fox, visits Henri Chrétien in Nice, as two of his collaborators (left) and the secretary of Chrétien’s Hypergonar lenses manufacturing company (right) look on. 1953, photograph, Nice, Cercle Henri Chrétien.

From 1985 onwards, activity at Victorine drew to a halt owing to the gradual switch from built sets to special effects. Following two decades of limited operations at the studios, a revival project was launched in 2018 by the Mayor of Nice, Christian Estrosi, with plans to appoint a company to set up shop at Victorine in order to co-manage it, alongside the municipality.

125 miles away, Provence Studios, which was established in Martigues, near Marseille, in 2013, is also showing strong Hollywood ambitions. This year, it hosted its biggest project yet: The Serpent Queen, based on Leonie Grieda’s best-selling Catherine de Medici – Renaissance Queen of France, which tells the story of the queen consort from 1530 to 1570. The series is being produced by Lionsgate for Starz. The six-month shoot, which saw the creation of over 300 jobs, took place both in southern France and in the châteaux of the Loire Valley.

The south of France has a rich movie heritage crying out for consolidation, and it is determined to create a local industrial network capable of meeting the exacting standards of Hollywood productions. As France’s second most popular region for film shoots, and with annual economic spinoffs estimated at over €130 million (US$150 million), local authorities are aiming to modernize their film infrastructure and train future technical crews. This second goal is already underway, with the opening in 2018 in Marseille of a new branch of filmmaker Ladj Ly’s Kourtrajmé Film School, the introduction of the ENS Louis-Lumière continuing education program at the Victorine site (October 2021), and an Audiovisual and Immersive Creation master’s program (September 2022).

Partners in Hollywood have also shown keen interest in the region following Amazon Prime’s announcement, on October 13, 2021, that it was launching a screenwriting workshop there, the Victorine Narrative Lab, created by Sylvie Landra and Sébastien Cauchon. Coming hot in the heels of the TIFF premiere of Amazon’s first original French production, Mélanie Laurent’s The Mad Women’s Ball, this news attests to the platform’s wishes to strengthen its ties with the French creative community.

Ville de Nice

In Nice, Villa Rex Ingram is home to the management of Victorine Studios. Nestled between the Mediterranean and hillsides in the hinterland, the location is strongly reminiscent of California.

American producers today see France generally, and the French Riviera more specifically, as a land of opportunity in the context of the explosive worldwide demand for content (British and Canadian movie studios are booked out for years to come). The continued trust built with partners in Hollywood explains the renewed choice of France as a favorable working climate. Nice-based producers Raphaël Benoliel and John Bernard (who also works from Paris) have been responsible for hosting first-class American productions, such as Woody Allen’s Magic in the Moonlight (2013), which was shot in part at Nice’s Observatory, and Opera, but also Mission Impossible: Fallout (2018), Stillwater (2021), Emily in Paris (2020), and The Serpent Queen (2022).

French professionals have proven, time and again, that they are capable of meeting American demands, and that clichés about labor costs and bureaucratic red tape aren’t having a chilling effect on Hollywood companies.