Belonging as an Act of Justice

© Daniela Andujo

By Terence Lester

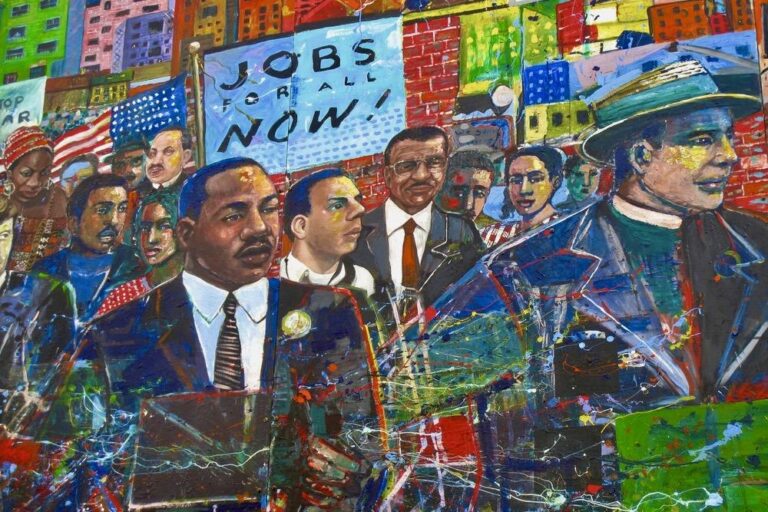

Activist and researcher Terence Lester investigates the roots of hostile architecture and its impact on homelessness and discrimination. Drawing from personal experiences of racism in the Jim Crow south, Lester explores the intersection of race, class, and homelessness. As hostile architecture further marginalizes those without an address, this article illuminates the power of belonging, re-imaging homelessness through the Lens of Martin Luther Kings’s b “Beloved Community”, and urging readers to confront systemic barriers for a more inclusive and just society.

The first time I learned about hostile architecture, I was 17 years old. The brake booster had just gone out on my 1981 Baby Blue Box Chevy, so, my mother encouraged me to call my grandfather Carlton York, a mechanic, to see if he could fix the problem. He invited me over and taught me two lessons I’ll never forget. The first was that he wasn’t going to fix the car for me. He told me to grab a tool from the toolbox and he’d fix it with me. I remember walking over to a rusty toolbox and grabbed the wrench among tools that looked like that traveled through a few generations.

Not knowing if I grabbed the right tool he spoke up and told me, that “searching was a sign of learning…” The second lesson came when I told him I didn’t think I’d be able to fix the car because I didn’t understand the tools. That was his opportunity to teach me a history lesson: My grandfather had a way of turning a car into a classroom. He told me how he’d grown up in the Jim Crow south and how every single day he fought hard laws and buildings designed to remind black people, “You don’t belong…”

Now, Granddaddy wasn’t telling me this because he didn’t think I could fix my car with his help. He was teaching me that everything he had to overcome was so that I could fix it. He was reminding me of how there was a hostile world out there that did everything it could to remind him and my family and those stained with the pain of racial hatred that we weren’t worthy and just didn’t fit in.

He said the type of Hostile architecture that he faced were when, water fountains reminded us that we weren’t welcome. Signs on buses or in restaurant widows reminded us that we had to wait, or enter from the back, and that somehow, we were not welcome.

He told me that public sanitation had always been at the core of what it meant to be excluded and to keep people that looked like him and I thinking that to belong, achieve, or to pursue anything beyond our sphere was impossible. This was the type of hostile architecture that acted as a violent racial reminder that home for some did not mean home for others.

This was the first time I’d ever heard about what that lack of belonging in society looked and felt like—while looking in my grandfather’s aging eyes. But sitting in that 1981 Chevy, my grandfather told me that I belonged to a larger community: a Beloved Community.

He taught me that belonging is about value, and value had everything to do with the inherent worth and value that I possessed—that we possess. He reminded me that on April 15, 1960, Martin Luther King, Jr. gave a speech in Raleigh, N.C. and spoke these words as found in the King papers at Stanford: “It must be made palpably clear that resistance and nonviolence are not in themselves good. There is another element that must be present in our struggle that then makes our resistance and nonviolence truly meaningful. That element is reconciliation. Our ultimate end must be the creation of the beloved community. The tactics of nonviolence without the spirit of nonviolence may indeed become a new kind of violence”.

He taught me that I belonged to a community that was bigger than the one defined by hatred: the Beloved Community. You see King’s shared idea of the Beloved Community was a society where all members were valued and included, where justice and peace prevailed.

My conversation with my granddad became the impetus of how I ended up in a PhD program studying public policy, and researching how public policy has been used for centuries to define the worth of those who are poor and unhoused in this country—but specifically those who are unhoused. I have spent the past years researching the five periods of homelessness in the U.S. and how social and political rhetoric over the years move homelessness from a social issue to a criminal one. Forty-plus years of criminalizing public policy that has connected homelessness to the criminal justice system and has been a direct attack on the sense of belonging one has who they do not have an address. My research had me grappling with the questions: How did we get here? Why is it that when a person hears the word ‘homelessness’, why do they automatically think of two things: drugs and mental health issues? Forty-plus years of public policy shaping societal views on homelessness, determining who is deemed worthy and deserving and who is not—which has led to a harmful narrative that keeps those without a permanent address from being fully accepted as part of a Beloved Community (Christopher Herring).

All this helped me to understand the three narrative constructions of why people believe that people are poor and unhoused as defined by sociologist Teresa Gowan:

- Sin-talk: This is the narrative where people believe that people poor of unhoused because somehow they are morally wrong;

- Sick-talk: This is the narrative when people attempt to explain away the poor by suggesting that it is a lack of wellness that has caused them to be where they are;

- System-talk: This is the narrative where people understand that systemic issues that causes people to end up unhoused.

I was fascinated by Gowan’s three constructions of poverty because each category had punishment and exclusion as the way people addressed this issue. And because these narratives fuel the social framing of those who are unhoused, my research led me to develop research questions that, in turn, led me to the state of Tennessee wondering how public policy impacts a sense of self-worth and keep those from the Beloved Community.

I chose Tennessee because it was the first state in the United States of America to make sleeping outside a Class E felony for the unhoused, which comes with a felony charge, up to six years in prison, and a loss of voting rights. And when you have a felony, it is harder to get a job and get access to housing. I chose to focus on the state of TN and decided to journey there to turn my dissertation into a documentary. When I landed in Tennessee and conducted ethnographic research, I saw a different form of hostile architecture: as had my grandfather had seen, I saw urban design that sought to visibly erase the poor from the public eye. I saw hostile architecture that was not just against as race of people, but not against a social class, and it make me think about the intersection of race and class and how at foundation of hostile architecture is the idea of erasure. Erasure is always a threat to belonging because belonging is about visibility.

To be seen and heard is a powerful reminder that we are here and that we are human. Hostile architecture, then and now, is always about public sanitation and never about the visibility of those who are worthy. Spikes, fences, boulders, and signs littered across cities remind those who are poor and unhoused that they do not belong—especially if you have no address. When homelessness is criminalized, individuals are often seen as criminals rather than individuals in need of assistance, which can lead to further marginalization and exclusion from larger society. This dehumanization further perpetuates the cycle of poverty, homelessness, and criminalization, making it even harder for individuals to find stability and access the support they need to rebuild their lives—this is why belonging is so important, because in order to rebuild somewhere, you must belong somewhere.

Speaking with the unhoused in the state of TN, while conducting street interviews, I discovered that home is about where you feel seen, accepted, and are able to develop meaningful relationships—it’s a place where you belong. While homelessness itself is about the lack of a physical space. I remember seeing how ‘affordable housing’ was not affordable, even for those who have jobs. I remember speaking to Howard, a brother who went from living underneath a bridge to having his own apartment and doing advocacy work for those who are without and address, and him telling me “that affordable is not affordable to those who are unhoused…”

This caused me to realized that the state created a law to make it illegal to sleep outside, but had more people unhoused that beds that were available. And instead of creating more space, these cities created more laws to take away one’s ability to belong. The more I traveled, the more stories I heard that went counter to the idea of King’s Beloved Community. His Beloved Community evokes interconnectedness, interrelatedness, interdependence—and all this is about home, about seeing the world as a shared address, about the type of home where all are welcome—and this type of belonging is an act of justice. My research led me on a quest to figure out how I could center the voices of the unhoused in a way that gives them an opportunity to reclaim their place in MLK’s Beloved Community—and that has been through the power of Voice (King Center, 2022).

Through counter narratives I found that people experiencing homelessness can tell their own stories and find belonging by using their own Voices. Because who are we to write policies that have real time effects without including stakeholders and the unhoused in on the conversation?

Who are we to believe narratives about those we have never even had the chance to meet? When we extend belonging to those experiencing homelessness, we are working towards creating a society where all members are valued and included. Because belonging is about Voice, I had an idea to create a museum that combats the stereotypes and social constructions that frame this community as not being worthy of being a part of the whole community.

This Dignity Museum is housed in a shipping container and travels from place to place to provide narrative justice for those who have been excluded due to public policy and social opinion. And we have had all types of visitors: we have had police officers, policy makers, K-12 students, educators, College Students, Churches, Corporations, Real Estate Agents and a whole spectrum of individuals who have chosen to come and immerse themselves and learn about how do we show in a world and extend more belonging and empathy to a population of people that is often times excluded. This is a space that allows people to belong to a narrative that is much bigger than the narratives that have been used to label and limit those who are unhoused merely because they are journeying through the worse parts of life.

The museum houses the oral history of people who have journeyed through living underneath bridges, sleeping in tents, and having to endure the coldest parts of the year with no access to warmth. It gives voice to those who been living out of cars with their families because they can no longer afford the rent in their neighborhood. It gives voice to those who have been laid off of jobs or struggle to find a job that pays a living wage. This museum is all about silencing social and political rhetoric that seems to frame this population of people as being unworthy to be a part of a Beloved Community. Because belonging is revolutionary. It’s revolutionary because, as King said in his Letter from Birmingham Jail “All men are caught in an inescapable network of mutuality, tied in a single garment of destiny”.

This network of mutuality includes those experiencing homelessness. We must recognize the importance of belonging and its power to create a more just and inclusive society. When we extend belonging to those without a permanent address, we affirm their worth and dignity as human beings and recognize the importance of prioritizing their human rights.

We challenge this narrative of the ‘deserving’ and ‘undeserving’ person experiencing homelessness because of failed housing policies in the 1970s-80s. We must also recognize the value of human life and affirm the worth and dignity of those who have the courage to journey through poverty each day.

So, when we talk about ideas, let our ideas include creating space for those who are unhoused to use their voices. Let our ideas be ones that provide narrative justice for those who have been framed by people who have never experienced what its like to be poor. Let our ideas be grounded in the truth that even those without an address are still our neighbors. Let our ideas think of new ways to include those who have been criminalized by public policy by affirming their humanity. Let our ideas be fueled by the type of love and compassion that deconstructs the false notions that being poor or homeless somehow means you are not worthy of contributing to our world.

We might think belonging is small, but it is not: Belonging is an act of justice because it acknowledges the inherent worth and dignity of every individual, including the unhoused. Belonging is an act of justice because it recognizes the systemic barriers and injustices that have led to homelessness and seeks to address them. Belonging is an act of justice because it promotes social inclusion and helps to combat the stigma and discrimination faced by the unhoused. Belonging is an act of justice because it provides a sense of safety, stability, and community, which are essential for human well-being and flourishing. Belonging is an act of justice because it centers the voices of those who have been oppressed. Belonging is an act of justice because in a world full of hostile architecture, belonging is justice.

References :

Centre Martin Luther King Jr. pour le changement social non violent (25 février 2022). The King Philosophy – Nonviolence 365. Consulté le 13 janvier 2023 sur https://thekingcenter.org/about-tkc/the-king-philosophy

The Martin Luther King, Jr., Research and Education Institute (24 mai 2021). Consulté le 8 mars 2023 sur https://kinginstitute.stanford.edu/king-papers/documents/statement-press-beginning-youth-leadership-conference

Terence Lester is a Ph.D. Candidate and the founder of the non-profit organization, “Love Beyond Walls,” which strives to raise awareness and provide aid for those experiencing homelessness. With a desire to better understand the individuals his organization serves; Lester spent a month living among the homeless in Atlanta. He also had the opportunity to create the Dignity Museum, the first museum in the US dedicated to representing homelessness. In 2018, Lester humbly participated in the March Against Poverty, a 386-mile walk from Atlanta to Memphis, where he had the privilege of speaking at the Lorraine Motel for the 50th anniversary of Martin Luther King Jr.’s assassination. Terence has written six books, including “I See You,” “When We Stand,” and his forthcoming work, “All God’s Children: How Confronting Buried History Can Build Racial Solidarity,” set to release in June 2023.

This article is based on his contribution to the Night of Ideas in Atlanta on March 4, 2023.