Aunt Charlie’s Lounge: The Untraceable Queer History of San Francisco

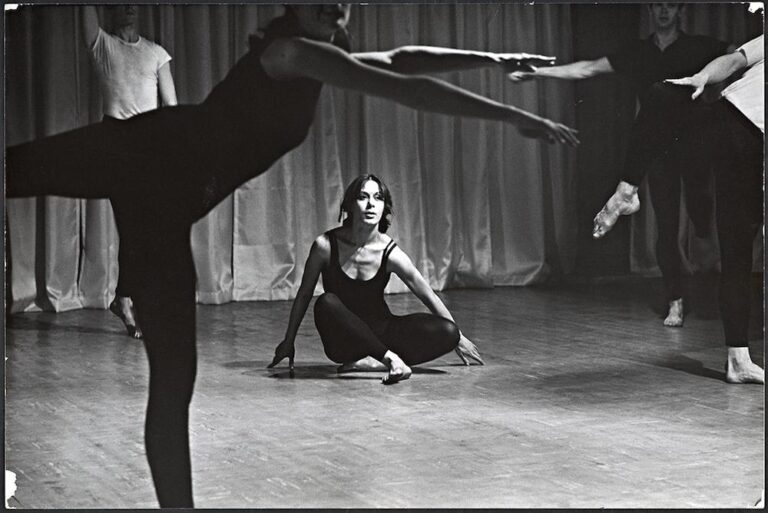

Hélène Giannecchini © Sabrina Bot

By Hélène Giannecchini

What is left of San Francisco’s queer history? Writer Hélène Giannecchini came to SF with Sasha J. Blondeau and François Chaignaud, with whom she is preparing the show “Cortèges” for the Philharmonie de Paris. Though the hoped-for encounter with her story is more difficult than expected, there is one place that brings back all of those who have left their mark on the history of struggles for LGBTQIA+ rights: Aunt Charlie’s Lounge.

It is nightfall when I land in San Francisco. At customs, I wait in line for my turn to speak to a youngish man staring blankly from behind a grubby glass pane. Snatching my passport, he takes a good, hard look at me, asks me where I’m staying, who I’m going to meet, what I’m doing here, how much money I have in my bank account, and so on and so forth. Welcome to America, indeed!

Earlier in the day, sitting on the long and beautiful flight over, I followed the setting sun, tried to distinguish the various snow-capped peaks as we skimmed across, watched bad movies, ate potato chips, and napped. I haven’t traveled this far across the globe in years. Now that I’ve arrived, I feel like I’m swimming upstream to start my life anew. Very soon, my American days will occur during French nights. I tell myself that not a single email or phone call can reach me directly here, and the very idea puts me in a state of barely concealed euphoria. I’ve gone off the grid. Even better, I’m in San Francisco for the first time in my life.

The airport is deserted. I was expecting a huge space swarming with people, but there are only a handful of travel-worn tourists. I see my friend Sasha, recognizing his walk from the other side of the arrivals hall. I hurry over and give him a hug. “I’m here!” I exclaim. “Holy shit, I’m in San Francisco, Sasha!” The two of us exit the airport, get into a waiting car and speed towards the city. I try to make sense of its language of steep hills, opulent houses, and trees I don’t know the names of. The taxi leaves us at the top of a hill, we pay and I drag my suitcase up a few more yards. I’m exhausted and happy. The apartment has a windowed corner with a view that stretches on towards the lights of the harbor. And that dark, indistinct mass delineating the horizon is the Pacific!

There are three of us staying in the apartment–Frannie, Sasha and I–and we are not here by chance. Our identities and struggles have brought us together, and we want to bring them to the stage in a play combining contemporary music, dance, and literature. It’s still early stages, and we have so many questions on our minds. How can we prevent our ideas from being hijacked now that we are formalizing our vision? Will we manage to make something beyond tasteful yet hackneyed queer theater? Do we still have enough room to express our rage, and will it be understood properly? I mean, can anger still be heard in a prestigious, 2,500-seat theater, or will it just be embellished and made more palatable? We’re not sure of anything, but we want to try it all out.

It makes sense for us to be in this particular city, a city that contains part of our history. At least that’s what we tell ourselves. We look for this history in the city’s streets, bookstores, bars, and parks, thinking about how the battles that took place here shaped our lives. In France, I feel cut off from this memory, where it doesn’t carry the same weight and emerges only in fragments from specific little nooks. Sometimes I need to place my life within another form of genealogy, where I can find new ties and bonds, because the dominating heteronormative narrative is not my story to tell. I want to find solace, too, leaving behind the anger that has all too often resided in me ever since our identities became desirable, appropriated like stylistic motifs or devices to be altered at whim. It is this somewhat naïve attitude that has brought me to San Francisco. On the first morning, as the bay breaks slowly through the mist, I think to myself that I am in the right place to find what I’ve been missing.

There is indeed great joy here: the Technicolor houses, the coffee shops, the city’s sloping topology that follows the curve of my own excitement, the pervasive smell of weed, the complete works of Anne Carson that I find in the first bookstore I walk into, the roaring ocean striking me whenever it appears. I like it here, at the other end of the world, all lain out beneath a fluorescent sky the likes of which I have never seen. But as I leave the beach on my first evening, I see young men—still in their teens and dressed in baggy shorts, baseball caps and flip-flops—stepping out of flashy red Maseratis and sleek Lamborghinis. The streets are also rife with Teslas (whose handles I can now easily recognize), luxury stores, pretentious and exorbitantly priced cafés, and organic supermarkets where a single vegetable costs an arm and a leg. Downtown, meanwhile, around Civic Center, populations shift and bodies transform, zombified by drugs and wasted by poverty. In the evening, the streetcar passes through a tumult of jumbled soliloquies and unanswered shouts of distress. The homeless and addicted perish outside deserted malls, where glassy-eyed sales assistants wait for people to come in for their overpriced, fake-chic clothes and fancy sneakers. “Capitalism is visible here,” I think to myself. “It is visible and even flaunted.” You literally have to step over bodies to purchase a new pair of Nikes. One night, a stoned old man falls out of his wheelchair and collapses in front of a restaurant window. The diners hardly bat an eyelid. I remember the dull thud of his fall, the tiny suspended pause that follows and then, immediately, the kale that enters mouths again, over the sound of clinking glassware. The waiters look on emotionlessly at the body slumped in a heap. It doesn’t exist or, perhaps, just barely. Like a habit that people no longer speak of. I wonder what can be done about all of this violence.

Another day, we explore the depressing streets of the Castro, seemingly bereft of all lesbian and trans life. Rainbow flags are imprinted immaculately onto the asphalt, however, making you feel like you’re in a Nike ad on Pride month. After wandering a short while, we make a beeline for what will soon become our favorite bar: Aunt Charlie’s. It’s in the Tenderloin, an area of San Francisco that we have been warned about countless times. “Don’t go there,” people tell us, “especially not at night. Just don’t.” And for good reason: it is the poorest, most run-down district in the whole city, far removed from the sandy beaches, green mokas, trendy terraces, menus for dogs, verdant lawns, and luxury thrift stores. The Tenderloin is San Francisco’s underbelly where, for over a century, all the misfits have gone to eke out an existence. It is the realm of unmarried women, blue-collar laborers, prostitutes, queers, junkies, and all the rest. The first time we visit, the weather is beautiful and the whole city buzzes under a clear blue sky. It makes me almost gloomy, all this light. We spend the morning at the harbor watching seagulls and container ships gliding over the ocean, then walk back up to the city center. Since arriving in San Francisco, we have gotten used to walking for miles. Occasionally we’ll take the cable car, the Bart, or even an Uber on evenings when American-sized servings of gin and tonic keep us from finding our way home. When we first enter the Tenderloin on this bright, sunny day, we are taken aback by the bleakness of it all, the sheer brutality of the living conditions. I keep telling myself, “Capitalism is visible here. It is visible and not even trying to hide its awfulness anymore.” Here are all the freaks, all in the same boat: the destitutes, the washouts, the cripples. They drop like flies in the filthy streets while Big Tech big shots continue to amass their millions just a few blocks away.

My hopes of getting in touch with my history are seriously starting to fizzle out. I have to face up to the fact that none of it really exists anymore. My best bet would be to speak to some of those who lived through this history, who are now old and wealthy enough to sustain a life in this city. Then again, it’s not all bad. There are also some amazing archives in San Francisco, such as the SF Library and the GLBT Archive Society, where I spend hours poring over hundreds of photographs. The scenes are etched into my memory: a lesbian couple in matching cowgirl hats kissing in front of a gas station in the 1950s, a drag queen shouting gleefully and gesticulating in a blur of joy and celebration, the candlelit vigil following the assassination of Harvey Milk, torched cars lighting up the city during the White Night riots, dykes and fags from an anti-AIDS militant group sitting hand in hand to block the Golden Gate Bridge… Yes, my memory finds these images and stories here, but they are remnants of a bygone era. This San Franciscan history is no longer really alive. You only have to look at the glittering, perfectly pinkwashed Castro District. “It’s all over, now run along,” it seems to say. I feel like Sasha and I are seeking to revive this history as we traipse through the Tenderloin, steering clear of the ubiquitous rainbow pins and ‘Trans Power’ fridge magnets. We are waiting for some feeling to hit us. Perhaps it’s time to take off our pristine archivist’s gloves and get our hands dirty.

Picture a brick building, a neon-red sign, a standoffish doorman who looks you up and down, asks for $5 and helpfully adds that there’s an ATM inside if you don’t have any cash. Then picture a narrow corridor running along a counter, a dirty carpet, a few high tables at the far end, a warm atmosphere. Look at the people leaning on the bar: ordinary looking older men, whose bodies tell of tiredness, pennilessness and, sometimes, sickness. Welcome to Aunt Charlie’s!

Two minutes into our first visit, a man invites us over to celebrate his birthday. Given his state, he has clearly been on the beer for a few hours now. He wears a checked shirt and has just a few teeth left, hidden under a thick mustache. He jokes around and makes us laugh. The barman looks a bit like a sober, slightly older version of him. He has a tired expression, his hair is graying at the temples, and he probably should have retired a decade ago (if such a thing even exists in this country). To his left is Olivia Hart, the real star of Aunt Charlie’s. She entertains the crowd and serves drinks, sporting an enormous wig and a red-sequined dress. We take a seat and order two gin and tonics. We are immediately enthralled by the place, this hot mess of a dive bar. We feel like we stick out ever so slightly, but it soon embraces us. As we sink into our booths, aglow in the pink light, we end up having such a good time that it becomes our favorite spot. That’s settled. Next to us, two girls in ball gowns appear to be on their first date. Both overexcited and wearing heavy makeup, they knock back vodka shots every fifteen minutes while stroking each other’s hands.

At 10 p.m., the drag show commences. The queens sashay down the corridor, performing one lip-sync after the other and taking one-dollar bills from patrons to stuff into their cleavage. Even the barman gives them some of his tips, delighting at the pirouette that follows whenever they take a bill. Perhaps his offerings are also a show of solidarity. We are enchanted by the outfit changes, the stunning dance performances, the uproarious jokes between the numbers. But there’s a certain something that moves us even more. This is not some pre-packaged pageant. The queens change behind a crudely stapled-together curtain, their bodies do not fit the ‘standard norms,’ their vulnerabilities are visible and that’s what’s so wonderful. We can see all the tricks. Although it’s all for entertainment, it takes on a certain authentic truth that leaves me completely spellbound. Picture the goth queen who sulks throughout her whole show, the seventy-year-old Donna Persona still dancing like a charm, and Olivia Hart, snatching off her wig to end her spectacular solo with her scalp shining under the spotlight. Here we are allowed to be nobodies: an aging homosexual who has seen his friends and lovers die, a bunch of clueless tourists, dykes in ball gowns vomiting up their eight vodkas. We can even be broke, since the drinks are twice as expensive everywhere else! It doesn’t matter, we just float over drowsy floods of music and alcohol. And, for some reason, even though Sasha and I do not belong to any of the above categories, we feel like we’re in exactly the right place. We’re much more at home here than at the trendy bars of the Mission. Among our own.

The previous day, we’d been out walking and passed by Aunt Charlie’s, unaware that behind that filthy door was one of the most joyful places in the city. We were with Susan Stryker*, a San Francisco-based activist who specializes in trans history. We’d met earlier in the day, for a chat in her garden. Sasha and I turned up twenty minutes early, as is our trademark. We watched the trees on the street for a bit, commenting on the façades and houses. On Stryker’s garage door is a mural that depicts her, with her girlfriend. Behind them is the Mission and Bernal Heights Hill, with its antenna poking out and, to the right, the menacing arm of a trader and a tsunami of dollars rising up, ready to take out the whole city in its wake. It’s a pretty neat summary, I thought.

In Stryker’s garden, we spoke of uprisings, anger, queer cultural appropriation, and invisible forms of solidarity that must be woven into our fight against the conservative backlash. It was a powerful, worrying discussion. She was trying to warn us. “Something is brewing,” she told us, “and we’ve got to be ready.” We hear the same worry in Judith Butler’s voice a few days later, who also remarks on the pitiful state of our democracies. With her, we discuss violence, friendship and mourning through activism. The two of them are right: something is coming. Back in France, I brood over both these interviews. “How can we fight what has yet to take form?” I wonder, “What exactly should we be preparing for?”

After our conversation, Stryker took us on a tour of the city. Standing right outside Aunt Charlie’s, she asked us to look up, pointing her index at the façade of the Gene Compton Cafeteria. Stryker told us of the riot that took place there in 1966. Three years before Stonewall, when the cops attempted another in a long series of raids, the trans women present defended themselves and resisted the police harassment. They stood their ground. Fighting back, they threw tables, coffee cups or whatever they were holding. This first act of courage marked the beginning of the civil rights battle for trans people, fags and dykes; the battle for our rights. It is a pivotal location in the history that I’ve been looking for in San Francisco, but have not exactly found. When I looked up at the building, I saw that the name had disappeared. All that was left was a plaque on the ground, which read:

Here marks the site of Gene Compton’s Cafeteria where a riot took place one August night when Transgender women and gay men stood up for their rights and fought against police brutality, poverty, oppression and discrimination in the Tenderloin. We, transgender, gay, lesbian and bisexual community, are dedicating this plaque to these heroes of our civil right movement. June 22, 2006.

It was strange to be there and not to see anything, not to feel anything. Stryker pointed at something else. Taking a closer look, I suddenly noticed bars on the windows behind which lone figures sat in the dim light. Stryker explained that the cafeteria had become a privately-owned prison, one of the most lucrative businesses in the US. This site of historic uprising had been turned into a place of coercive force! Penal and financial order now reigned where they once fought against the cops. Our memory had been obliterated for profit.

I thought back to the tidal wave of dollars on Stryker’s garage door, now witnessing its results before my eyes. Again, I told myself, “Capitalism is visible in San Francisco, as clear as day.” Its cynical spirit does not fear the paradoxical. In fact, it gets off on it. Here, capitalism swallows everything, taking us with it.

*Susan Stryker is a historian and theorist specializing in Gender and Women’s Studies. If I had to choose some gems from her extensive body of work, I would refer you to the 2021 augmented edition of her book Transgender History. The Roots of Today’s Revolution, Seal Press; the 1993 article “My Words to Victor Frankenstein above the Village of Chamonix”; and the 2005 film Screaming Queens: The Riot at Compton’s Cafeteria.