Where Are We Going? Atlanta’s Long Way to Go Before Becoming Wakanda

With the pertinacity of pain and trauma of the pandemic of COVID-19 and the ensuing global economic crisis, the persistence of racial injustice, and its related violence has thrusted Atlanta and all her promise into the public view. The world has called upon our city to reexamine perspectives on Black experiences and anti-Black racism. Pandemic, protest, and insufferable loss have brought us to the precipice of a new awakening to the ongoing challenges faced by our city and its marginalized communities. This moment reveals the urgency for reflection and critical thinking on the relevance of social justice and responsibility in the everyday experiences of Black Atlantans navigating racism and its effectiveness in fostering platforms on which Atlantans may thrive and gain full opportunities for self-agency. This essay aims to answer the question “Atlanta, where do we go from here?” Or, at least details where we can go from here.

In recent years, the world was smitten by Wakanda—a fictive Black nation so powerful that it thrives, and its isolationist policies protect it from anti-Black racism. White and conservative critics scoffed at this fictive land and failed to understand why Black people were so moved by Wakanda, only to miss the point and ignore that all societies—French and American; Black or White—are crafted by a shared set of values and culture. Quite simply, what we believe to be culture is merely the customs, arts, social institutions, and achievements, whose contours are shaped by local environs. Now let’s insert Atlanta.

While Wakanda has allowed for us to imagine a world where African descended people can live and breathe from under the western gaze, the question surrounding the Atlanta’s Wakanda-esque qualities persist. In August of 2020, I was interviewed by a NBC regional affiliate. The question was asked “Is Atlanta Really Wakanda?” I answered the question with an unequivocal and resounding “NO!” Drawing upon my training as an historian as well as methods in the social sciences, I have spent much of my early career interrogating this topic through discourse of Atlanta as a Black Mecca.

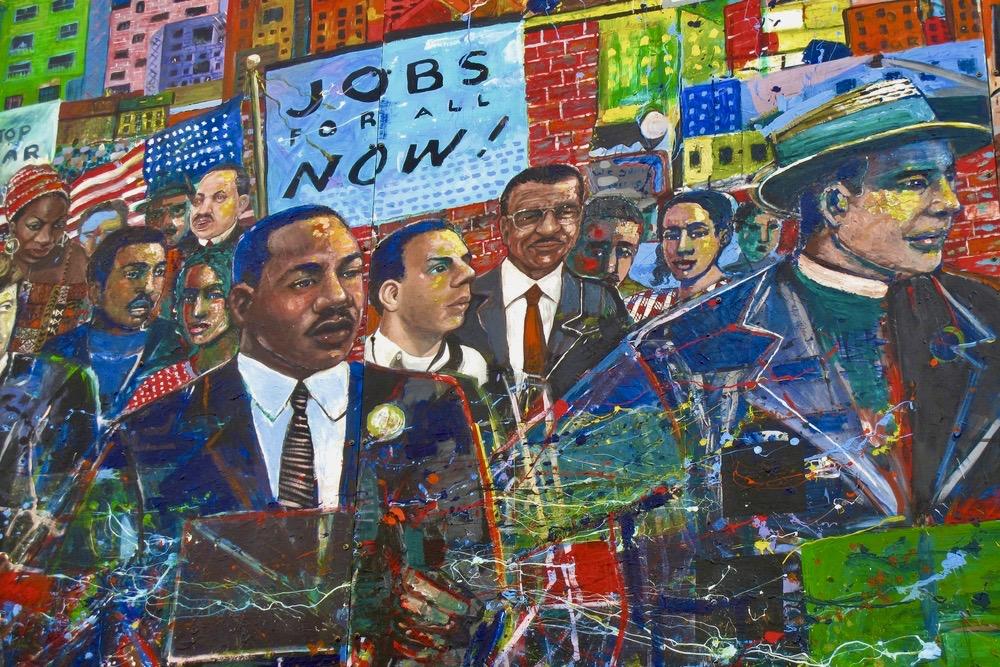

It is no secret that the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. is Atlanta’s most beloved son. Like clockwork, American Presidents, world diplomats, and ordinary citizens gather to honor the dreaming preacher who paid the ultimate price for humanity. Each and every January, King’s national holiday, and April—the commemoration of his death, the world praises a man who stood for social justice and equality, championed the poor, and criticized American capitalism and this nation’s involvement in world-wide conflict. Because King put humanity first, his hometown of Atlanta stands out as a beacon of progress and the “crown jewel” of the American South. Again, Atlanta is a scenario where Black and White; French and American; Russian and Ukrainian are granted access to life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness. Articulated in King’s language, this concept is known as the “Beloved Community—justice, not for any one oppressed group, but for all people.” Yet, in the aftermath of King’s assassination, Atlanta, America’s largest and Blackest city did not rebel—non-discerning civic leaders lazily propagated the message that the city’s nonviolence was based on good race relations, when in fact Atlanta’s Black communities did not burn because they sought to honor the wishes of the slain prophet.

After hard-fought struggle and subsequent political gains from the passage of civil rights legislation such as the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965, it was Atlanta who ushered in the symbolism of Black political empowerment and electoral politics with the election of Maynard Jackson as the city’s first Black mayor in 1973. While this was seen as progress, the 1970s and 80s were plagued by a series of events which included the Atlanta Child Murders, where the city’s most vulnerable yet vibrant citizens—Black children—were being hunted by serial killer(s). The fall of industrialization and the rise of the information age left Black and poor people drowning in unemployment. Ronald Reagan’s policies gutted any opportunity for a quality education and fair housing while the War on Drugs—a war on Black and Brown people brought on by crack cocaine—diverted funds from education to further augment the school to prison nexus. When President Ronald Reagan cut federal funds to American cities, Atlanta’s Black mayors had no choice but to expand the city through developments made by international investors with profit in mind, but no interest in helping the city’s poor. By the mid-1980s, Atlanta had the second-highest poverty rate in the country, a large homeless population, and a hypertensive high school dropout rate with a drug crisis and a recession. The arrival of AIDS crippled Black communities, and Atlanta garnered some of the highest rates of HIV/AIDS in the world.

Nevertheless, the International Olympic Committee selected Atlanta as the host city for the 1996 Olympic Games with the majority of votes cast by African, Caribbean, South American, Asian, and Arab countries on September 18, 1990, the same year that the city was deemed as the “murder capital of the world.” The city’s boosters suggested that Atlanta had outgrown the sordid history of race relations in the American South, and the cooperation between Black city government and the white business elite reinvented “Hotlanta”—the Deep South’s newest and most modern world-class city. But the glossy Olympic City version of Atlanta offered sobering counter-narratives as seen through the lived experiences of Black people on the ground. An example of this was the rise of the Dirty South hip hop movement where Atlanta’s scene expressly rejected the “Hotlanta,” “Black Mecca,” and “Olympic City” imagery, and instead, portrayed the lived experiences of the Black masses, which was anything but King’s “beloved community.”

Fast forward, in the summer of 2020, Atlanta—the purported “Cradle of the Civil Rights movement”—erupted with protest and pyre. Media outlets throughout the world reported these ruptures as a response to the deaths of Ahmaud Arbery, Breonna Taylor, George Floyd, and Rayshard Brooks. All of these murders were caught on camera or held evidence that was traceable. Even the worlds’ most indifferent and unconcerned renounced this showcasing of compensated state sanctioned police violence against Black people and declared these deaths as public lynchings. The then-Mayor, Keisha Lance Bottoms, flanked by Atlanta natives and rap artists Michael “Killer Mike” Render and Clifford “Tip” Harris, also known as T.I., held a press conference, urging citizens to go home. With the tone of a concerned but scolding mother, the Mayor stated, “We’re talking about how you’re burning police cars on the streets in Atlanta, Georgia! GO HOME!” Clifford “Tip” Harris elaborated, “Atlanta is a place where we can set the example of prosperity and we’ve done that for generations. People like Dr. King, Maynard Jackson, and Ambassador Young have paved the way for us. When everything else goes away…when you don’t get treated right in New York; when you don’t get treated right in L.A; when you can’t get treated right in Detroit; when you don’t get treated right in St. Louis; when you don’t get treated right in Alabama; Atlanta has been here for us…We can’t do this here. This Wakanda…it’s sacred and it must be protected.” In an emotional but subdued tone, Killer Mike articulated, “It is your duty not to burn your own house down for anger with an enemy. It is your duty to fortify your own house of refuge in times of organization. Now is the time to plot, plan, and strategize, organize and mobilize. It is time to beat up prosecutors you don’t like at the voting booth. It is time to hold mayoral offices accountable, chiefs and deputy chiefs. Atlanta is not perfect but we are a lot better than cities were and we’re a lot better than cities are. I am mad as hell. I woke up wanting to see the world burn down because I am tired of seeing black men die.” But the praise and blame of the mayor-turned-celebrity and celebrities-turned-politicos gives us a lens to understand that the decisions on what can happen lie with the people. Killer Mike was right, and Americans and Atlantans went to the polls and purged this nation of a rogue President and delivered the Senate in the name of democracy, only to be upstaged by a scary but failed coup d’etat.

You see, the strivings of the Black world, when focusing on civil rights and politics—citizenship and voting—and with the convergence of history, politics, and culture that is at the heart of Georgia’s recent push for democracy, beckons Atlantans to reimagine the world. If American democracy is to be reinstated and maintained, Georgia will deliver it.

But Atlanta needs a new story, something that presents the city as a solution to the problems that beset us. Today, we have an opportunity to make history by electing the nation’s first Black woman governor. Atlanta has in its grasp the power to truly make America great by embracing democracy, freedom, and inclusivity. Moving forward, it is my hope that that our city and state leaders will consider using all means to reform issues around public safety and policing; affordable housing; education partnerships for our children; options for poor and homeless populations; a respect for the preservation of Atlanta’s public history; urban development; public transportation, annexation, and consolidation; sex trafficking and safe places; access to affordable healthcare; disparities within the gender-wage gap; and an increase in minimum wages. As Atlanta goes, so does Georgia and the rest of the South. Be great Atlanta—let freedom ring from Stone Mountain to the world.

Dr. Maurice J. Hobson is an Associate Professor of African American Studies and Historian at Georgia State University. His research interests are grounded in the fields of African American history, 20th Century US history, power relationships in labor, oral history, ethnography, urban and rural history, political economy, popular cultural studies and the Black New South. He is the author of the award-winning book The Legend of the Black Mecca: Politics and Class in the Making of Modern Atlanta. He collaborated on various Netflix and HBO documentaries, such as The Art of Organized Noize, Maynard, Atlanta’s Missing and Murdered: The Lost Children, etc.