Sam Bowler and Digital Culture in Louisiana

Interview

© Jose Cotto / Cluturalyst

By Jalalle Essalhi & Camille Jeanjean

The rise of digital culture in Louisiana comes from pioneers like Culturalyst, a shared digital infrastructure for cultural communities. Interview with Sam Bowler, Founder and Director.

About Sam Bowler: Sam Bowler is a writer, sculptor, and technologist based in New Orleans, Louisiana. His work is focused on building emotionally-responsible, place-based technology that creates opportunities for equity, community, and art therapy. To that end, Sam founded Culturalyst, an online platform designed to make it easy to discover and directly support local artists and culture bearers. Culturalyst’s vision to enable the creators of local culture to be equitably compensated for their work.

What prompted you to create a platform like Culturalyst? What needs did you identify when you launched? How do you empower local artists?

I started Culturalyst after learning about the inequity in the cultural economy of New Orleans. To give some context – New Orleans is one of the cultural treasures in the United States and as a result, benefits from a tourism economy in which tourists spend around $10 billion per year while visiting the city. This spending is on hotels, restaurants, etc, but about 10% is spent on entertainment, which equates to about $1 billion per year in New Orleans, which you’d hope would be funneling back into the cultural community. Unfortunately, it’s not. Artists and culture bearers, the producers of culture, bring in roughly $20,000 in annual income, a large portion of which is already lost to rent, which has been driven up by over 60% in the last five years, due in large part to the pressure Airbnb has put on affordable housing.

The economic disparity that plays out in New Orleans, plays out in most cultural economies globally. The current design of cultural economies, tourism economies, don’t center the artist, they center the tourist, which is short-sighted from a sustainability perspective. We just hope people, artists, keep expressing themselves, rather than redesigning how they are resourced to ensure longevity.

I was learning about the cultural economy in New Orleans, while at the same time trying to become part of the cultural community as an artist. I have had a humble metal and mixed-media sculpture practice since high school. So, as I learned more about the inequitable economics, I also began to understand how little infrastructure existed to support the discovery and exchange of information about the happenings of local culture — there were no tools to find artists, organizations, or arts opportunities (grants, residencies, etc.) in a city that depended on artists to create culture in order to attract tourists whose spending kept the city running.

So, I had the lights turned on, so to speak, on how there had been very little artist-centered innovation in local cultural economies. And I grew up as the son of writer and had learned how powerful art and expression were as tools to explore oneself and to connect with other people — this is one of my core beliefs in life.

With all of this — my own belief in art and a new understanding of cultural economies — I started Culturalyst because I wanted to be part of building a sustainable, artist-centered cultural economy. I felt it wouldn’t be scalable without a deep technical component, so I learned how to code and how to manage large technical projects and with the help of Cliff Hall, an exceptional software architect, and a rotating team of believers, built Culturalyst into a network of cultural communities, each served with a suite of tools that make it easy to discover and exchange information on artists, organizations and opportunities.

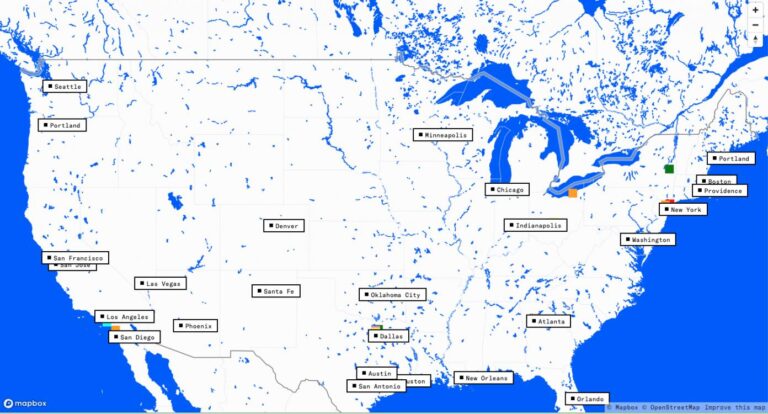

After experimenting with a few other models, I became interested in how Culturalyst’s infrastructure, designed to serve any cultural community, could become part of the public-good and funded in a similar way as built infrastructure — paid for by tax-funded institutions. As a result, we now work with state and local arts offices, who each pay an annual fee to bring our infrastructure to their communities. Our fees are on a sliding scale, allowing communities to join regardless of the size of their arts budget.

As a result, everything is free for artists, organizations, and cultural consumers, without the need for advertising. For each of these actors, we offer different tools, ranging from SEO-friendly portfolio sites organized in a directory, to a grant-sharing engine, to a backend data dashboard for arts offices to index and map their cultural communities.

Culturalyst © Brett Labauve

Our current offering fills existing gaps that allow Culturalyst to build both the reputation and the sustainability required to tackle the larger economic disparity at play in cultural economies. To use an analogy, we’re building the canals and the reservoir before we re-route the river.

We’re really excited by the feedback we’re getting. For some incredible culture bearers, who have been an integral part of the cultural fabric in their communities for decades, their Culturalyst portfolio is their first experience of a search-engine indexed online presence. It’s also the first time that they don’t have to go out searching for grants and opportunities. We now send them an email with all of the opportunities filtered just for them. And for state and local arts offices, they now have much deeper insight into what resources are available in their communities — the number of open grants available at any given time, the total dollar value of those grants, the number of artists applying. We’re currently in 12 communities and will be growing into many more next year, though I can’t officially announce where yet.

In general, Louisiana being considered a cultural mecca, how would you describe the place and dynamism of digital in creative work there? What areas for improvement do you see? and what would be the levers for action?

Louisiana has a complicated history, deeply shaped by colonial conquest, the ruthless exploitation of people and land for profit, but also a real gumbo of cultural influence. It’s at once French, Spanish, African, Caribbean, and American, and as a result, the traditions and expression of the people in Louisiana are unique but also deeply familiar in so many ways. And these are traditions that found their rhythm as a way for people to survive, to make meaning, to connect to a distant home, to maintain a cultural independence. Inherently, in my opinion, what makes people remember Louisiana is that its traditions and cultural expression resonate on a human level, so I think it’s hard to share via a new digital medium without losing some of that essentially human magic. I’m sure this could be said of a lot of cultural places, but it’s something at play in Louisiana too. Looking ahead, our goal with Culturalyst isn’t necessarily to keep people consuming digital media, though we hope to offer the ability for local artists to share their work in a more focused, ad-free environment. It’s to utilize the accessibility that digital tools provide to make discovering, resourcing, and eventually directly supporting local artists easier. Right now, cultural communities don’t have many tools to actually find and access the source of local culture, the people who create it. Not to mention tools to share information about opportunities for funding, residencies, open calls, resources — the stuff that really keeps artists moving forward, financially, artistically. So, the progress that we’re pushing for is to make all this basic stuff – discovery, resourcing, sharing, and again, eventually supporting — easy and accessible via digital infrastructure, so that people who create culture can continue to evolve their practices, online and offline, in the direction that makes the most sense for them, artistically.

Culturalyst aims for the discoverability of works. How would you sum up the work you’re doing for this purpose?

Cultural discovery is happening all the time on social media, but the experience of local cultural discovery can feel less straightforward. If I’d like to find artists in a city that work in sculpture or textiles, or understand the poetry being written in a city at a given moment, it isn’t easy. I can search by hashtags, but the ocean of algorithmically sorted content served to you isn’t really designed for you to understand how the artists are thinking, living in the city.

What we hope to accomplish with Culturalyst is to create an accessible space that centers local culture — the artists and all the work they want to share, alongside the opportunities, the organizations, the information about the heartbeat of a local cultural community. I hesitate from saying “local” artists too often, because I don’t think artists think of themselves that way, but what we’re trying to do is build a space that centers the artists who live in each place. And who that centering serves — from the artists networking, to tourists searching, to arts organizations or local governments resourcing — allows Culturalyst the rare opportunity of being able to keep evolving to meet the needs of multiple actors. It’s early days, but we’re designing with the intention of becoming as standard as the built infrastructure that informs how we move through a place. In the long-term, for example, we want everyone equipped with the tools, resources, and know-how to navigate holding onto a creative practice as they “grow up”, so to speak, wherever they grow up. And we’re committed to ensuring this space doesn’t become a mall. We’ll never show artists work next to an advertisement for teeth-whitening. As a related aside, it makes me really nervous that social media is the dominant platform for sharing and discovering art. It is an exceptional tool for potential virality and reaching scale, but because its existentially profit-motivated, it can subvert the creative process in so many ways — comparison, extraction of attention, flattening of creativity, consumerism.

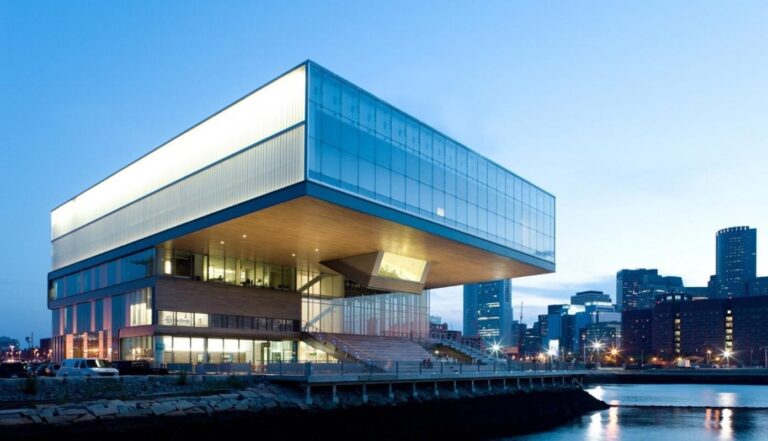

Speaking of discoverability. In recent years, immersive experiences have become increasingly popular, in museums for instance. For some, these uses are a wonderful opportunity to democratize culture, sometimes even to present works in digital format that would be impossible to transport in their physical form. Others, on the other hand, worry about the risk of standardization that could result as it’s often the best-known artists who are put forward, while the diversity of artistic movements overlooked. What do you think about this?

I think that creating more access to the arts is a good thing, though it’s critical to ensure that the access also leads to more equity in representation and exposure.

Immersive exhibitions allow more people to experience an artist’s work or may attract a different type of audience to a museum.

These experiences have primarily highlighted the best-known artists, Van Gogh for one, with the justification that it is the natural starting point in order to the make the funnel of public interest as large as possible and that over time, as more people learn to value immersive exhibitions and form a relationship with museums, the diversity of artists and movements will increase.

That said, it needs to be stated that “the natural starting point” often centers white, male artists, which continues to normalize the white patriarchal, colonial perspective as the default. This has to be challenged at every decision and unfortunately, equity in representation and diversity in perspective can take a backseat to profit and relevancy as the prioritized motivation.

I’d also argue that there are ways to increase access to the arts that don’t still require folks to enter a museum, even if that museum now has lasers and projections. Utilizing a combination of online and offline experiences, we could be finding ways to share with communities the work of artists from that community. Or even across communities. Imagine the impact it would have on a whole generation of aspiring creatives if current artists from different cultural communities were marketed and shared across the country with the same resources as Van Gogh.

What are the leading professional events and festivals in Louisiana?

I think you’d be hard pressed to find a place that does festivals as well or as often as Louisiana. It’s part of the culture here. The Jazz & Heritage Festival and Essence are big annual events in New Orleans. In other parts of the state, you have smaller festivals like Festival International de Louisiane and Blackpot Festival & Cookoff in Lafayette. I’m not too familiar with the other festivals around the state, but I know each community has at least one that is an annual celebration of local culture.