Yolande Zauberman: “I have a firm belief in the political power of intimacy”

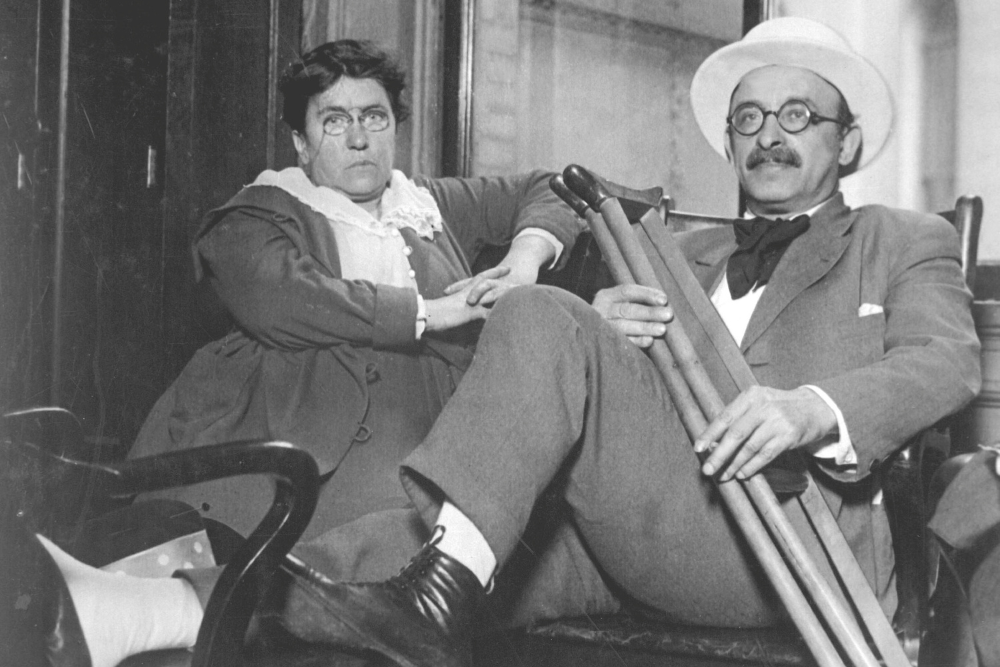

Emma Goldman and Alexander Berkman

By Raphaël Bourgois

Emma Goldman was a figure of anarchism, a political movement whose significance at the turn of the 19th and 20th centuries in the United States has since been forgotten. Filmmaker Yolande Zauberman came to New York to follow in the footsteps of this young Russian Jewish refugee, who became a powerful woman and a public figure of feminism and workers’ rights. Here is an intimate—and therefore political—portrait.

Could you start by telling us who Emma Goldman was? You decided to devote a film to her. That’s what made you go to New York for research, wasn’t it?

It’s worth pointing out that Emma Goldman is well known in the US but little known in France. She was a Russo-American anarchist and feminist intellectual whose life went from the second half of the nineteenth century to the first half of the twentieth century. This woman fascinated me. Not only did she join the anarchists’ struggle for an eight-hour working day as early as the end of the nineteenth century, but—above all—she fought for women’s right to enjoyment. For her, the right to vote wasn’t enough: you also had to resolutely remove society’s prejudices from women’s minds so they’d feel equal to men. This was very important as it was about getting women to see they could enjoy their rights and body and could love whoever they fell in love with, whatever their sex or skin color, without feeling like they were debauched. Through Emma Goldman, we get a picture of anarchy at the time, both in the US and beyond America’s borders. It was the main left-wing movement then and you sense a form of awakening in her and all those around her. These people would toil day and night. They were exhausted, but their evening political meetings, parties, and conferences would raise them up and make them feel like real humans, not just workhorses. This movement gave each person their own humanity back by taking all individuals into consideration and suggesting a system that would tear down a structure where some gave orders and others obeyed. By pulling down this structure imposed on them, experience of life itself could begin. I don’t see this film about Emma Goldman as a documentary—that genre is more fitting when you want to address the present and see history in the making. Instead, I want the film to be like fiction, a great romance, a mix of politics and desire. For me, it’s more interesting to embody this desire for freedom and sexuality, this need to give dignity back to work, the body, and love. She’s described as maternal, sexy, flamboyant, powerful, and funny. She should be given a chance to express herself, not given an outside voice that speaks for her.

So how was Emma Goldman seen during her lifetime?

What’s funny with Emma Goldman is that she often got into trouble with the justice system but was always proven innocent. The press and police were under her spell to some extent. For those in power, that made her even more dangerous. She got labelled as the most dangerous women in the US but never committed any crime. Yet that didn’t stop the justice system hounding her. For example, when a young man fired a gun at the US president, he said the last person he’d heard talking was Emma Goldman so she was accused of inciting violence. But she was later cleared: of course, she had nothing to do with the case, even if she defended the young man. Only when she started talking about women’s rights did she end up in jail. She was imprisoned for publicly championing birth control in 1916. Puritanism back then—which is still around today—made any line on women’s rights incendiary, particularly when it touched on women’s bodies. What’s more, Emma Goldman stood out from her time as she wouldn’t make moral judgments. She tried all jobs —she even tried to become a prostitute but was told it wasn’t for her. She had many lovers, but for her whole life loved the first man she met when she arrived in New York—Alexander Berkman. Her belief in the individual and experience—perhaps one of the greatest things—was what truly defined her.

You said Emma Goldman is little known in France. How did you first find out about her?

Almost all I know about Emma Goldman I learned when I stayed in New York. But I first heard about her while listening to a radio show called Les Chemins de la philosophie (‘Philosophical Paths’) on the French radio station France Culture: she got mentioned in an episode on anarchy. What mainly interested me about her was that she inspired many philosophers and people of her time who were anarchists but wouldn’t say so openly as admitting to it was like admitting you were mad and violent. Yet we can draw a parallel with today’s world. For me, many recent events like the Arab Spring and city squares being occupied (such as Nuit Debout in France or Occupy Wall Street in the US) rekindle the memory of Emma Goldman. It was striking to see young people rebel against the political and economic system they lived in, regardless of context, yet without laying claim to power or pursuing domination. Other political paths can be pursued. And Emma Goldman was an ancestor of this approach.

One remarkable aspect about Emma Goldman was that she was hardly ever mistaken—and when she realized she was mistaken she’d admit it. For example, she backed the Bolshevik revolution, but after going to Russia and seeing people die in the street and the lack of free speech she realized she’d been wrong about it. She then even confronted Lenin himself, grilling him about the lack of free speech in the USSR and about the executions of anarchists. After that, she told the world what she’d seen and this caused tension with her left-wing friends, who then shunned her. She’d immigrated to the US in 1885 and become a US citizen in 1887. She loved America deeply, but had to flee the country because of her convictions. In the end, Peggy Guggenheim offered to put her up in Saint-Tropez, as she did for James Baldwin years later. There, she wrote her autobiography Living My Life, which was published in 1931 and won acclaim when it came out, despite disappointing sales. She was allowed to go to America for ten days to talk about her book. She then left the US and died a few years later in Canada in 1940.

You’ve touched on her relationship with the US, but how was her relationship with New York, where she lived? Why was it important for you to spend time there?

By being in New York, I’ve been able to explore the places where she lived, like East Village and the café she arrived at on her first night there and would then regularly go to. I was able to see the New York of her time, the district of dressmaking unions that would represent seamstresses, furriers and suchlike—the heart of the Yiddish-speaking community of Jewish emigrants. She arrived in New York with just a sewing machine and a Yiddish newspaper’s address. Yiddish was the only language she spoke at that time apart from Russian. She gave her first conferences in this language before switching to English. She was also in touch with Mexicans, Italians, Spaniards and Ukrainians, so was in a very international environment. Indeed, when you look at the women she supported and those who supported her, you see they came from many different countries. Many aspects defined her at once: she was from the East, she was Jewish, she was a woman, she was in love, she believed in the individual, and she was driven by great optimism about people and by great pessimism about power.

So you sought to research the atmosphere and backdrop in which Emma Goldman came to New York from Russia in 1885. But I imagine there are other sources, aren’t there?

I dug deeply into archives, especially the Emma Goldman Papers, a project that brings together her writings. The police would track her, so I was able to get hold of reports and records of some of her interrogations. Each time she was arrested, she’d mount her own defense without a lawyer and her speeches were transcribed in the press. She had a real audience. There’s also some archive footage we can find in documentaries. It’s worth noting she wasn’t especially beautiful objectively, though she was described as highly attractive—that says a lot about how liberated women were portrayed at the time. I always look at the eyes a lot: in these films from Emma Goldman’s time where she appears among other anarchists I see a form of alertness, even though these people should have been ground down by their living conditions. It’s not a militant’s alertness, but the alertness of someone who’s discovered they can be in love with their life. There’s a form of happiness and joy. These beaming faces are one of the most beautiful things you see when looking at this footage from history—and you can still see it today in France among some young people who have revived the notion of desire.

This approach based on the private life runs through all your work …

I have a firm belief in the political power of intimacy. I’ve often witnessed it. In particular, I witnessed it when I shot my first film in South Africa: Classified People (1988), which should be coming back out in America soon. Everyone was pessimistic about the apartheid and the violence it brought. But I wasn’t: I saw a glimmer in the eyes of those I met. If that glimmer couldn’t create something wonderful then I knew nothing could. And I believe my eyes. The film has remained ageless, even though it was produced in an extreme context in 1986. The underlying question it asked was: how do you live in a situation where you’re classified and designated as being legally and socially inferior? The answer offered by those I filmed—directly or indirectly—was that the only way to resist was via the private life. It was later said I invented this concept, but actually those people taught me it. That film changed my life. At a time when I distrusted everything political I suddenly found something political I could study and love: the private life of those people. I was shooting a film in South Africa in the midst of riots and a risk of imprisonment. I was filming—using a reel—an elderly couple of lovebirds tell me their story in that society. It was as if time stood still. Thirty years later, even with the apartheid abolished, the film still rings true.

I also adopted this approach when I made the film Would You Have Sex With an Arab? in Israel. I carried on raising the issue of the private life because to desire someone you’ve got to first see them and recognize them as a person. That’s when you realize the scope of politics extends all the way to our beds. When I shoot a film, I never seek to give moral lessons to those I film. I make mirror-like films as a way for me to respond to questions I’m actually asking myself, to which I’m actually looking for answers. They’re experience-based films—I’m passionate about this approach and it’s the approach I plan to adopt again for Emma Goldman.

French filmmaker Yolande Zauberman, a multidisciplinary artist who works in documentary and fiction, video and narrative arts, has forged her own path of expression. She began her career with “Classified People” (1987), a documentary on apartheid in South Africa, which was awarded the Grand Prix at the Paris Festival and the Bronze Rosa at the Bergamo Film Festival (Italy), among other prizes. Shot in India, her second film, “Caste criminelle” (1989), was screened at the Cannes Film Festival. In 1992, she turned to fiction with the Cannes Film Festival Award of the Youth-winner “Ivan & Abraham”. In 2011, “Would You Have Sex with an Arab?” was screened at the Venice Film Festival. In 2020, her film “M” won many awards, including the César for Best Documentary Film.

Sign up for the Villa Albertine Magazine newsletter