Where Are We Going? Towards the United States of Europe

By Hugo Toudic

How may the European Union draw inspiration from the “Federalist Papers”? No less than the secular bible of the American Republic, this work signed James Madison and Alexander Hamilton offers a reflection on sovereignty which, according to Hugo Toudic, should serve as the basis for Europeans’ questionings. While the invasion of Ukraine by Russia compels us to rethink the question of sovereignty, the EU gains a new lease of life, becoming once again a horizon where the question “where are we going?” may be answered.

The Europeanist – Article 1

AFTER an unequivocal experience of the inefficacy of the subsisting Fœderal Government, you are called upon to deliberate on a new Constitution for the European Union. […] It has been frequently remarked, that it seems to have been reserved to the people of this country, by their conduct and example, to decide the important question, whether societies of men are really capable or not, of establishing good government from reflection and choice, or whether they are forever destined to depend, for their political constitutions, on accident and force. If there be any truth in the remark, the crisis, at which we are arrived, may with propriety be regarded as the æra in which that decision is to be made; and a wrong election of the part we shall act, may, in this view, deserve to be considered as the general misfortune of mankind.

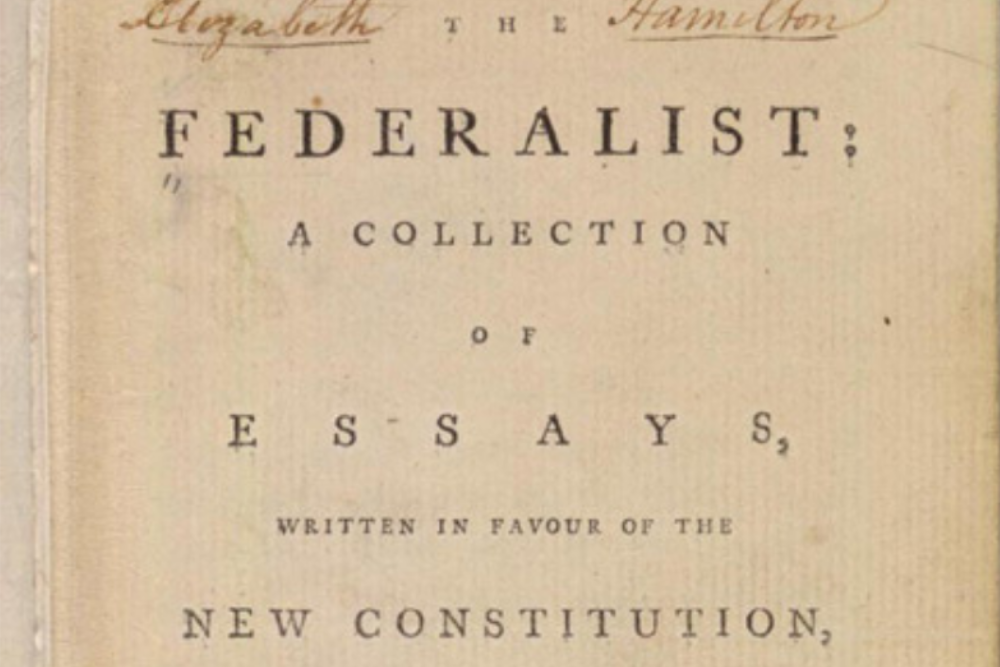

The astute reader will have noticed there is no such thing as The Europeanist. At least not yet. This quotation is nothing else than the exordium of a text each American citizen has heard about during their civics class: The Federalist. Written almost entirely by James Madison and Alexander Hamilton during the ratification debate of 1787-1788, this collection of 85 essays addressed to the citizens of New York would quickly become the secular bible of the American Republic. In truth, there is no example of any other political pamphlet acquiring such glory and praise. The Federalist is the most quoted text in Supreme Court rulings; it pervades most politicians’ campaign discourses and one of its redactors has even attained glory on Broadway quite recently. The Founding Fathers bequeathed not only a republic to their heirs, but also attached to it a sort of user’s guide. In the course of the 85 essays, comprising hundreds and hundreds of pages, the reader discovers the hopes and doubts of the advocates of the new federal government. At some point, it even seems that such length and depth is unnecessary: wasn’t it a done deal after all? Not so fast.

The reader should not content herself with only reading The Federalist, because it is just one part of a much more complex story. Madison and Hamilton did not leisurely decide to write the 85 essays of The Federalist; they were compelled to do so. Madison was maybe the first to feel the urgency to write a federalist answer to all the criticisms the proposed Constitution was receiving. In one letter of October 21, 1787, to his friend Edmund Randolph, James Madison wrote: “A new Combatant however with considerable address & plausibility, strikes at the foundation […] the whole tendency of [his] piece, in this important crisis of our politics, [is] very hurtful.” Indeed, three days before, a letter had been published in the New York Journal under the name of Brutus. By choosing this Roman alias, the staunchest opponent of the Constitution showed he was on a mission to save the soul of the republic from the tyrannical ambitions of the federalist camp. The federalist response arrived on October 27, 1787, and it began with the very text that begins this piece, with some slight adjustments. After this little detour, I dare think the reader has a better grasp of why Hamilton’s prose feels so intense. The Federalists knew how much of an impact Brutus’s arguments had on the American public; they not only had to initiate a dialogue, but a convincing refutation.

One of the main reasons why Madison and Hamilton were so worried about Brutus’ arguments is because he used a weapon of devastating power: De L’Esprit des Lois or The Spirit of the Laws. In his first Letter, he peremptory rejected the proposed Constitution because it contradicted Montesquieu’s teachings on the appropriate size of the republic.

No man is a prophet in his own country, and the saying applies admirably to Montesquieu. His political philosophy was much more discussed, debated and refined on the other side of the Atlantic than in his motherland. He provided the American Founding Fathers with conceptual devices able to evade most of the intellectual pitfalls inherited from elder European philosophers. When Bodin and Hobbes had claimed sovereignty could not be divided, Montesquieu opened a path towards a graduated comprehension of sovereignty. States could maintain certain sovereign prerogatives while relinquishing others, such as the right to declare war and print money. When the same authors had expressly insisted upon the importance of an all-powerful sovereign, Montesquieu devised the separation of powers as the only way to produce and preserve political liberty. When all philosophers had contended that republics were a thing of the past, Montesquieu made a distinction between the old republics and the modern ones, based more on economic prosperity and less on virtue. He even paved the way, as Hamilton had noticed, to a democratic form of federalism.

Only a few months ago, as France started presiding over the European Council, the European Union was embroiled in seemingly unending political controversies. Not a day went by without a new book denouncing the overreaching power of the Union upon its members. Those critiques were not irrelevant per se, but they seemed sterile because they too often fail to acknowledge their conceptual premises. Most political speeches calling for the return of a true sovereign France or Italy rely on a Hobbesian or Rousseauist vision of sovereignty, where the nation state enjoys complete authority. Today however, as the Russian invasion of Ukraine has made the world more unstable and dangerous than ever, the paradox is that European states appear way more independent within the European Union than outside of it. The federative republic advocated for by Montesquieu and established by the United States Constitution had precisely as its primary goal to allow republican states to defend themselves against despotic empires.

The constant complaint about the absence of a European people was another argument against the federalization of Europe. Those regretting this absence were eager to point out that the United States were able to form a federative republic only because they were already a unified people. This is not only plainly false, it also ignores the many processes taking place in the creation of a people. Certainly the EU is now living a “Ukrainian moment”. Today, President Zelinsky is asking help from the European people as a whole. Suddenly, in the middle of the greatest crisis of our times, French, Germans, Polish come together not only because they realize they share democratic values, but also because they are now ready to fight for them. People unify in adversity.

Europeans, along with their American counterparts, are the heirs of the Enlightenment. They will not be forced to join a new empire, but they can be persuaded to enter a novel republican federation. It is precisely because the war is at our doorsteps that we need more democratic discussions and not less. We need to show to autocratic regimes that democracy never thrives as much as when it under attack. After The Federalist, we believe it is time to write The Europeanist.

Hugo Toudic, a PhD student at Sorbonne-University and Chicago University-CNRS, is a specialist of the influence of Montesquieu’s political philosophy on the ideas of the Founding Fathers. His field of study includes Political and Moral Philosophy, History of the Early American Republic, Constitutional Law.