Nacera Belaza: “I always try to get back to some sort of unknown”

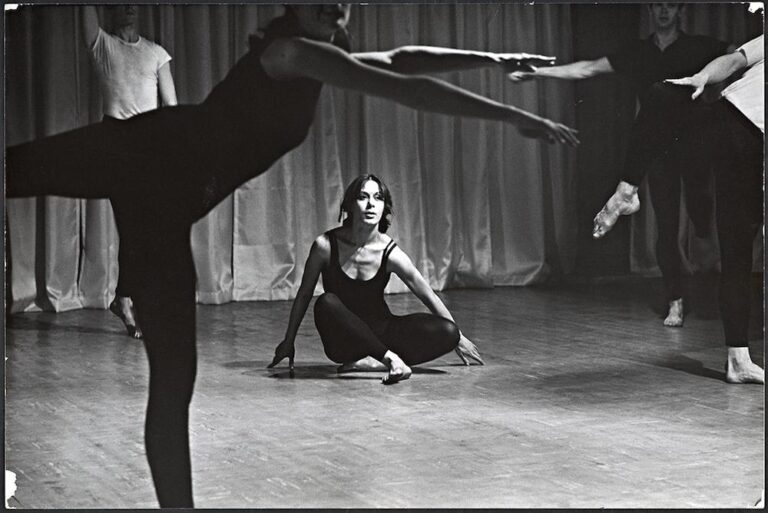

Nacera Belaza

By Raphaël Bourgois

“If you approach the world with sincere openness, everything can turn into chances to enjoy vital things and create new inner dimensions”. Leaving behind her over-scheduled life, dancer and choreographer Nacera Belaza embraces trances and the American wilderness to nourish her creation during her residency with Villa Albertine. Embark on a journey at the heart of New Mexico’s dry landscapes, and meet some Mormons, Native Americans, and a crow…

Why did you choose this travelling residency?

For thirty long years now, I’ve gone from creation to creation, almost without respite. In my first ten years as a choreographer, in Reims, I worked in a fairly relaxed context, with long waiting times between each creation. But over the past twenty years or so, ever since I moved to Paris, projects have come one after the other. Each of us has their own way of regaining strength. Mine is to keep some downtime for finding inspiration. Sadly, this downtime has been missing badly from my schedule. For a long time, I’ve dreamed of a period free of all needs, in which I could look to the future without a program or schedule. Each time I’ve imagined this period, I’ve mentally associated it with deserts, roads, and the Big Country, either in Algeria or in the US. To find inspiration, doing nothing isn’t enough as the pandemic confirmed: you’ve also got to be on the move.

That was the frame of mind I was in when an opportunity arose for a travelling residency in the US with Villa Albertine. So I was able to put together a journey based on my own areas of interest, including my interest in Native American culture. There’s a whole history of music in America that’s very spiritual and it touches me deeply. The pandemic sadly hampered some of my plans–I wasn’t able to visit pueblos where I’d hoped to witness Native American rituals. But that actually turned out to be a blessing in disguise, because I was able to truly set off on an adventure, with no plans and just my air ticket and first night booked.

Nacera Belaza

How does this search for downtime fit with your work as a dancer and choreographer? Did you find what you came to look for?

On stage, I always try to get back to some sort of unknown—new paths for the body, a way of letting go and putting myself in listening mode. This state is at the heart of my creations, but it hasn’t easily related to my lifestyle. On the plane, I wondered a lot about my approach, what I’d come to do in the US, why the need to travel so far to find inspiration, and the very meaning of such a residency. That was my frame of mind when I landed and I decided to drive to Santa Fe the next day. There, I learned all the pueblos were closed because of the pandemic. Yet I really wanted to meet Native Americans, as I’d always felt close to these people in a certain way—in all created things they see a sacred dimension, an invocation of spirits. This mental and bodily state has always touched me, and it reminded me, strangely, of something we find in Algerians. Having undergone brutal colonization and a civil war, Algerians no longer look to the future—they’re inward-looking with deep sorrow and hurt. But when I arrived in the US, I remained unsure about my outlook—I was looking for a sign to confirm it wasn’t misguided. So I decided to stroll around Santa Fe and meet people in the street. And I found myself in front of a store where many patrons were Native Americans.

Before I carry on, I must mention one crucial thing that was a decisive factor in the rest of my trip: my brother died in July after a very painful, long-term illness. It’s so hard to bottle up grief inside a human body, and even harder to do so inside a city apartment. For me, the residency was also a chance to find empty spaces into which my grief could spill. So I went into that store and began talking with a young lady, who introduced me to a Frenchman who worked there. His name was Ali, just like my brother! I then learned there was a community of fifty Algerians in the region. The first forename I heard in a region very far from home was that of my brother—I felt it was a response to my doubts. It was a physical, rather than an intellectual, process: I knew I was meant to be there. From then on, another part of my being supported what I was doing. Gradually—by visiting the region, going back to Albuquerque’s museums, immersing myself in the place more, and spending time in nature—I started noticing my body changed its listening mode. Instead of fitting in with a plan I’d pursue here daily, it was somewhat disconcerted. It didn’t really know where to go. It was listening to signals other than those it usually responded to. That was precisely what I’d come to look for.

And that was when you decided to hit the road on a whim…

Yes. I headed for Flagstaff, AZ. On the highway, I saw a sign for Mormon Lake. Impulsively, I decided to get off the highway. That’s something I wouldn’t have been able to do if I weren’t in this frame of mind, with such freedom of movement. So I left the highway and headed towards Mormon Lake, as the Mormons were also, in the back of my mind, one of those communities I wanted to explore. They fascinate me because of their capacity to shut themselves away and withdraw from society. I finally got to the end of the road and saw two men and two children unloading a truck. They were clearly surprised to see me. I went up to them and said I was looking for Mormon Lake. One of the men explained the lake had dried up. And then we began chatting—the human contact was intense, as these people lived on virgin territory and weren’t used to talking with foreigners. I was attentive, in listening mode, though slightly apprehensive. But I really felt something vibrant unfolding. I told him his country was beautiful, and he replied there was no other country more beautiful, apart from Afghanistan perhaps. I then learned he was a veteran and that this Mormon camp was made up of veterans. Something stirred inside me. I was shaking with anxiety but at the same time I was so glad to meet and talk to them. When I set off again, I told myself such openings don’t actually occur in everyday life, or at least we don’t notice them anymore—those roads off the beaten track we take without planning or forethought that can lead us anywhere and are vital forms of the unknown. In my work, I seek to recreate the unknown, risk, listening, but I realized I’d been doing so artificially, a bit like an oxygen tank you use to survive. We should always live that way.

Nacera Belaza

Your work in choreography explores trances, and the relation between the body and spirituality. Have you experienced anything new in your journey that could inform these explorations?

Yes. I had a very troubling encounter with a crow. I’d parked my car in the middle of the desert to take time to meditate, and I asked for a sign again. The sky was blue. There wasn’t a single bird on the horizon. Everything around me was empty. Then a huge crow landed three feet away! I felt something very strange about its presence. I got back in the car, drove about seven miles and stopped again, this time in Petrified Forest National Park, to take a photo. As I turned around, I saw that the crow was there again. It had landed and appeared to be in no hurry to fly away. It was very unnerving. Three women passing by spoke to me about it—they pointed out that it was strange to see such a bird there. I ended up going back to the car. I got in and shut the door. The bird was still near the three women, who were taking photos. And then, in an instant, it was right next to my car. I broke into tears. The women passed by me again and saw me crying because of this bird that was clearly following me, as they said themselves. They asked me if I’d lost someone recently and if I’d asked for a sign. I later learned that, in Native American culture, crows are messengers between the world of the living and the world of the deceased. I set off again, until my car had a technical problem. That’s a situation that’d usually make me panic, even if it happened in Paris. Here I was, in the desert, and neither my satnav nor my phone had a signal. It was then I realized something. I felt as if I was being told, through the crow, that I should let go of my fears–those were the words that hit me: “Let go of your fears.” At that moment, I felt like a heavy burden was being taken off my shoulders. I was almost crying with joy when I set off again.

What have you taken away from these experiences?

I’ve realized how important downtime is. When you plan life, you’re forever split between what happened yesterday, what’s going to happen tomorrow–and there’s just a small part of your that’s is in the present. But if you approach the world with sincere openness, everything can turn into chances to enjoy vital things and create new inner dimensions. I’d like to apply that to my life, to make it a daily practice. Yet in our busy lives, how can we find those spaces where we listen to ourselves before we act? That’s the whole challenge of creation—taking a scheduled period on stage and turning it into a vibrant moment that forces people back into the present. What this initial residency phase has shown is how much it’s become vital for me to keep these moments of downtime in my life. In my choreographic work, I’m always seeking to recreate these spaces where one feels whole. But when that process stays confined to the stage, when lifestyle doesn’t feed, infuse, and take over from it, the approach wears thin. That’s the challenge–a vital force that has to connect the stage with everyday life. It can be difficult, because art infuses my everyday life, of course, but the opposite isn’t always true.

At the start of this interview, you compared Native Americans and Algerians as groups of people who underwent colonization. When did you see this for the first time and how does it influence your work?

It’s something I realized four years ago, in Ottawa, when I heard a sound—a Native American chant that struck me. Whenever I hear music or a sound, I immediately know whether I’ll use it, because I only include in my creations what’s already in me, what speaks deeply to all I’m made of. This chant was a kind of cry, with a single drum noise, and cries, lots of cries. I used it in my most recent work, L’Onde (“The Wave”). I naturally wondered how Native Americans would perceive this use of one of their traditional chants, whether they’d see it as a form of appropriation. But there was logic in it, a powerful need for me to use it, because this chant formed an extension of another play, Le Cri (“The Scream”), from 2008, which paradoxically didn’t include any. I do so with great respect—it’s really relevant in my work.

But the question remains: what was it in this chant that spoke so deeply to me? When I went back to Algeria after the civil war, I was struck by people’s lack of foresight, a loss of faith in the future, a kind of self-repetition. I remember that when dancing there–it must have been around 2001 or 2002–I’d be told contemporary dance wasn’t part of Algerian identity. I’d hear things like, “Our identity is about traditional dance, not contemporary dance. We don’t want to open up to that.” I’ve sensed that in Native Americans as well. In a way, they know they puzzle and fascinate people, and they’ve built up a kind of facade for tourists. In the pueblos, you can see them dancing and living like they’re in showcases. All that prevents you from seeing how much these people are connected spiritually, including through chants and dance. That’s what I’d like to put on stage, though not in a didactic or folksy way. Things will build up; an alchemy will develop–it’ll never be a direct, unmediated depiction of what I’ve experienced and just recounted to you.