Experiences of the Anthropo-Scene – “Moving Earth” and “Matters”

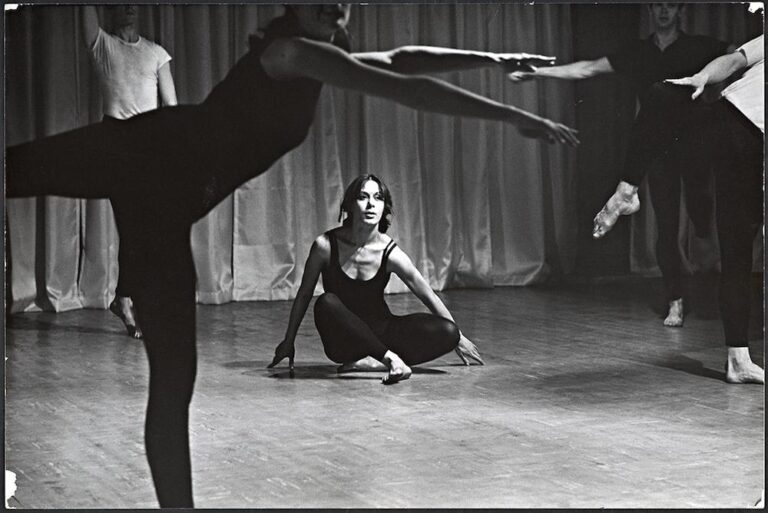

Photo du plateau de Moving Earth ©ZoneCritiqueCie

By Frédérique Aït Touati, Duncan Evenou & Clémence Halle

While theater is often considered the “art of the human” par excellence, it has become one of the primary venues for questioning the non-human and the more-than-human. The plays “Moving Earth” and “Matters”, presented on December 2 and 3, 2021 in Atlanta by the Georgia Institute of Technology, the Alliance Française and the Goethe Zentrum, show the contribution that theater can make in the era of the Anthropocene, as well as question the link between the stage and the social sciences.

Only a few years ago, the world’s climate seemed like a specialized topic that could only appeal to climatologists rather than social scientists, let alone artists. So when Bruno Latour and I decided to write a play about the Earth’s climate, in 2009, the reaction of most theaters we approached was tepid, because the idea of a play about the global climate was foreign to them. They could not see the point. Today, no-one would question the relevance of the world’s climate as a subject in theaters—or anywhere else.

Theater is often considered the ultimate ‘art of the human.’ Yet it has now become one of the main places where we explore the non-human and the more-than-human. Is that a paradox? Not when you look at the long history of relations between theater and representations of nature, from the theatrum mundi of antiquity to the scholarly plays of the Renaissance. Theater can grasp issues that are bigger than the human condition; it is ideally suited to making sense of the cosmological sea change underway. If we want to go beyond our vision of the world as a fixed backdrop, theater is a precious tool for pondering a planet that has become active and reactive, for probing the metamorphic zone we are going through, where borders between nature and artificiality, between living and inanimate things, between humans and non-humans are shifting.

For the past decade or so, Bruno, my troupe, Zone Critique, and I have been exploring what could be called the Anthropo-Scene, and how the Anthropocene makes us rethink the role humans play on the world’s stage. When you look back at our projects, you can see them as chronological milestones that mark the successive shocks in our discovery of the new climate regime: we shared the distress of Gaia, a new figure crashing into our planet-stage (“Cosmocolosse,” 2010), upon its intrusion; we explored the emotions and madness caused by the new climate regime (“Gaïa Global Circus,” 2013); we brought non-humans into politics by inviting them to the climate negotiating table (“Le Théâtre des Négociations,” 2015); we reconsidered our images of the Earth and attempted to see the planet in a different light (“Inside,” 2016); we tried to grasp how the Earth moves and feels, and wondered which planet to land on (“Moving Earths,” 2019); and we explored the Earth’s consistency and entanglement with living things (“Viral,” 2021). From a performance involving several hundred participants in “Le Théâtre des Négociations” to a one-person-show, all these experiences explored the heuristic capacity of theater and made it a place for reconfiguring the forces and actors of our Earth-world.

The play we are producing in Atlanta is the second installment of the “Terrestrial Trilogy,” featuring “Inside,” “Moving Earths,” and “Viral.” Can we change the way we see the Earth? The way we walk on it? “Inside” invites us to walk on our planet’s critical zone, as scientists are calling it, rather than on its surface. This lecture-performance includes a series of visual tests and hypotheses that help us grasp what ‘living inside’ means by combining modeling and simulation tools. “Moving Earths” is a reflection on the political effects of such a major upheaval in our relation to the world. It posits a parallel between today and the 17th-century cosmological revolution, and recounts how James Lovelock and Lynn Margulis’ Gaia theory emerged. “Viral,” a work-in-progress, sees virality as a principle governing a planet made up of interdependent worlds, prompting us to rethink the space we build and inhabit.

To shift from philosophy to theater, from a traditional lecture to a show-based lecture, I suggested to Bruno that we use a hybrid format, halfway between the kind he was used to and a theater set. “Inside” and “Moving Earths” are lectures where Bruno plays himself (a philosopher and a lecturer) but appears immersed in his PowerPoint presentation or at work in his office, which fills the entire set. Each slide, each document becomes a scene—a theatrical backdrop that is no longer two-dimensional but fills every dimension so the audience enters the intimacy of a thought at work. The creative process does not stop on opening night. Each performance is a chance to clarify things, to explore developments and arguments, and to revise and adjust images, because the lecture was not written or read in advance; rather, it was improvised using the dramaturgic structure we had defined together, and tested in a visual and scenographic system through which expressive, physical and affective possibilities come to life.

In constant flux, “Inside” and “Moving Earths” are now embodied by Duncan Evennou. The actor plays out the philosopher’s ideas, rather than the philosopher himself. In our work process, he had to absorb the arguments so he could develop them himself through improvisation. For me, this is a crucial point: these shows were not written to be played out. They are improvised lectures, following a hypothesis tested in public in the theatrical system I put forward. They unfold so that the audience does not see a fixed demonstration being presented or firm knowledge being taught, but an idea emerging and taking shape before them. This is theater of thought. It is this particular process I try to capture in stage form.

The theater takes both the audience and the actors on a journey of shared uncertainty. There is no teaching here. We use the theater and scenography to simulate the researchers’ world—the concerns and uncertainty they explore. There is no reference to a specific body of knowledge. Our cosmological sea change puts us all in the same boat. The process of scientific discovery is the most dramatic, thrilling form of intrigue. Now that I can weigh up the whole of “The Terrestrial Trilogy,” this theatrical project looks to me like a long tracking shot, gliding from the planet to virology, from astronomy to biology—an attempt to find our bearings in this unknown land we call home.

Stage director and historian of science, Frédérique Aït Touati questions through her plays the relationship between fiction and knowledge, ecology and politics, and is performed on numerous stages in France and around the world. “Moving earths”, by Frédérique Aï-Touati and Bruno Latour, with Duncan Evennou, was presented on December 3, 2021 in Atlanta by the Georgia Institute of Technology, the Alliance française and the Goethe Zentrum.

Duncan Evenou – Matters

Matters is a stunning polyphonic solo inspired by a conference on the Anthropocene that took place in Berlin in 2014. A theatrical performance that seeks to repopulate contemporary imaginaries disaffected by the ecological crisis.

“Matters” is an hour-long one-man-show performed on a bare stage, with the sole prop being an old-style standing microphone on a round base. Dressed in white overalls, the performer steps to the front and is bombarded with a dozen voices from scientists, historians, and politicians, all wondering whether or not we have entered a new geological era. Through this collection of sounds, we have attempted to bring form to the archives of the inaugural “Anthropocene” working group meeting that was held on the stage of the House of World Cultures in Berlin, on Friday October 17, 2017, at 9 p.m.

We wanted to show how the notion of Anthropocene made its explosive entry into the arts and humanities. To achieve this, we needed a specific, local starting point to counter the theory’s aspect of globality, which leaves it so disembodied that it obliterates any desire or capacity to act. We chose to begin our story on the day that the international scientists first gathered in a physical space, tasked with assessing the legitimacy—or lack thereof—of this geological era. Clémence then transcribed all their speeches in the hopes of answering two questions, namely who this being called Anthropocene is, and where it comes from.

Following this, we pieced together a fictional transcription of the Anthropocene working group’s inaugural meeting, on the stage itself, assembling the dialog from the archive recordings instead of writing our own. This approach did not seek to erase our presence, but actually to let it creep in through the gradual polyphony that takes hold. Through the choices that guided us in composing our assemblage, a new voice began to emerge. We were now telling another story from the archives, treating the speakers as fictional characters expressing a wide array of arguments. This single idea resulted in many different imaginings, and provided the crucial components of our on-stage interpretation.

Upon their first encounter, the geologists, historians, and politicians handed the microphone over to one another, as each attempted to translate, in their own terms, the non-human temporalities that the Anthropocene theory invited them to consider. And so, too, do we pass from one voice to the next, playing the role of moderator, cautious savant, unbridled enthusiast, dedicated scholar, sarcastic catastrophist, robotic technologist, and self-assured journalist. We play dubious data-punchers, public critics, pragmatic overseers worried about speaking time (which, ironically becomes merged with geologic time), and, finally, the advocates of zoopoetics, who suggest that the audience put themselves in the mind of a confused owl in the night, observing this construction in which a handful of enlightened humans are all aflutter as they try to make sense of their actions.

These juxtaposing, disparate dialogs fluctuate between comedy and tragedy, helping to de-dramatize a dominant political discourse that is overly centered on action but falls flat when attempting to address the geological theory. As the performance takes unexpected turns, it reprises the esthetic of the endless, enumerated list of impacts that humans have on their environments, hoping perhaps to allow a new archive to be composed

Following several shared experiences on stage, we were becoming exasperated with all the standard discussions about the end of the world. So, in order to open up other possible narratives, we wanted to let the cracks show. We like to speak of a racket wherein knowledge becomes ‘garbled’ by the urgency to act. By letting this polyphony of utterances be heard, “Matters” seeks to rejuvenate current schools of thought that have become disillusioned by the ecological crisis. As a potential era, the Anthropocene asks us not to let ourselves be overwhelmed by this feeling of urgency, but to take time to consider the relationships between us, as agents, and our environments. In doing so, we can avoid replicating the very same logics that have led to its development. The stage is a place of experimentation governed by its own rules and tempos, sometimes involving a much slower pace.

This process has inspired us to look at other ways of depicting the world that we live in, rooting it in its environment. For us, being a ‘citizen of the Earth’ means departing from the approach of searching for new worlds, whether intra- or extraterrestrial. Instead, we must use what anthropology and environmental history can teach us about the nature-nurture split, allowing for alternative interpretations of our host planet. And so, we invite the audience to imagine how the collapse of one world can create multiple otherworlds, all existing inside the original, where actions are no longer separate from imagined fictions.

Invited to Atlanta on December 2 and 3, 2021 by the Georgia Institute of Technology, the Alliance Française and the Goethe Zentrum, Duncan Evennou (actor and director) and Clémence Hallé (researcher) presented their play “Matters”.