Atlanta, Black Identity and Echoes From the Atlantic

Cascade mythical skating ring in Atlanta © Raymond McCrea Jones

By Maboula Soumahoro

One can be a historian of the United States, a specialist in Black history and theories of Afrodiasporic descent, and yet be struck by the specificity of Atlanta. This was Maboula Soumahoro’s experience during her residency, and she concluded that theoretical knowledge—such as the conditions of emergence of a figure like Martin Luther King or of Hip Hop culture—does not replace physical experience in understanding how a Southern city became a major home for the Black-African diaspora.

The idea for my residency in Atlanta arose from my initial reflections on the Black/African diaspora and its roots in the Black Atlantic area. Throughout my education, I had become acquainted with United States history, cultures, demography, and geography, particularly in relation to the country’s divisions between North and South, as well as between East, Midwest, and West. But despite my knowledge of the history, cultures, and theory of the Afrodescendant diaspora, I had admittedly never given proper attention to the city of Atlanta as a standalone research topic. This is perhaps because I spent a long time living in the United States, experiencing the country as a whole rather than as a theoretical case study. As well as this, I most often transported my body—as a Black woman of African descent—around the area of the Northeast.

Spending an extended time period in Atlanta later allowed me to experience the South with all of my being, freed from a distant, shallow view over the region produced by the comforts of abstraction. I was already aware of the concept of sectionalism–the territorial division of the country into two cultural and, more importantly, political zones whose decades-long confrontation inevitably led to the Civil War. However, I had never considered the extra-national dimension of the South. Certainly, I was well versed in the history of the Civil War and the events that occurred between 1861 and 1865, due to the divisions between the North and South, which nearly saw the dissolution of the entire political entity. But I had not fully taken into account the place of the Southern Black African diaspora in that history. In other words, I had not heard the echo of the Atlantic ringing through the very name of Atlanta.

How could I have overlooked the importance of Atlanta to this diaspora descending from the forced displacement of millions of Africans—men, women, and children—during the transatlantic slave trade? An essential factor in the advent of the modern era in the West, this tragic event had nonetheless formed the core of my research. One reason for the oversight might be geography, since the inland city of Atlanta does not border the Atlantic. But the history of the Black/African diaspora should not be limited to the transatlantic slave trade, which constituted only one step in a long journey.

This journey began in the African interior, where individuals were hunted and captured before being transported to the West African coasts. From here, some embarked on the arduous crossing over the Atlantic Ocean, following the trade triangle known as the Middle Passage. They eventually arrived in the Americas, usually through the gateway of the Caribbean, before being sent off to the various colonies or nations of the New World to satisfy their various demands and needs. As a result, these ports of entry all bordered the Atlantic.

The United States began as a colony under the British Empire, and then later emerged on the global stage as an independent nation between 1776 and 1783, during the War of Independence. Over the course of this timeline, both Northern and Southern States operated active slave ports along their coasts. It is vital to consider the multiple dimensions of this trade, both international (being essentially intercontinental) and strictly national. Regarding the latter, once the enslaved individuals arrived in the United States via the Atlantic, they were dispatched across the entire territory, North and South. Even when the transatlantic slave trade was abolished in 1808, it remained possible to purchase and sell enslaved individuals in the country, right up to the Civil War.

After the Southern States were defeated, the largest Confederate monument to commemorate the War was erected, some twenty minutes from Downtown Atlanta. It is located in a vast estate (now housing a museum) named after the former Confederate president. Here, proudly billowing in the breeze are the flags of the eleven Southern States that made up the Confederacy, each accompanied by its own commemorative plaque bearing the precise date on which it became a member. Even more remarkably, these eleven flags and plaques combine to form a sort of guard of honor, surrounding a gigantic bas-relief hewn into the mountain, all in homage to the men considered to have been the three most important Confederate leaders.

You really have to see it to believe—and understand—it.

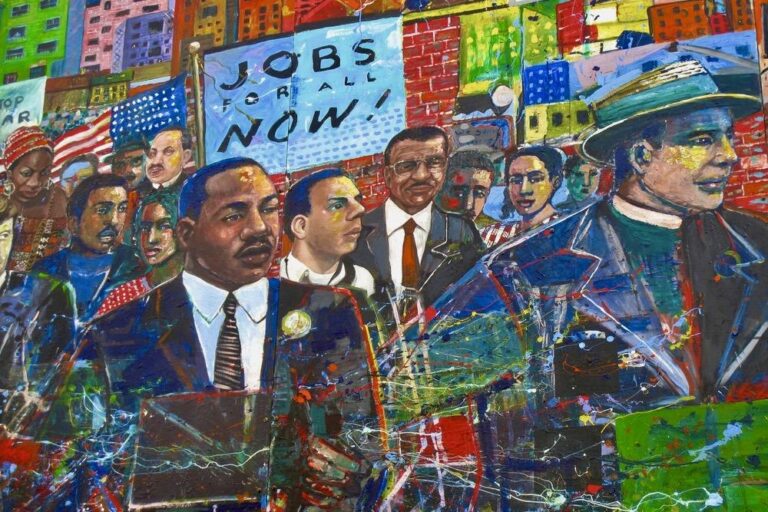

We must seek to understand the vastness and centrality of the race issue in the United States, whose Black roots are embedded in the very bedrock. To understand how a powerful figure like Martin Luther King, Jr. could arise from the lands of Georgia, then leave behind such a strong familial and pastoral legacy. To understand the presence of HBCUs, such as Spelman, Morehouse, Clark Atlanta, and the Interdenominational Theological Center, and their endeavor to shape African-American leadership from generation to generation. To understand the dynamic energy of Atlanta hip-hop cultures present in every part of the city, from streets to institutions; from every art form to every academic discipline; from nightclubs to strip clubs. Indeed, at a time when hip-hop was mistakenly believed to belong only to the East and West Coasts, the iconic A-Town rap group, Outkast declared that “the South got something to say.”

Lastly, it is important to understand that—much like Harlem in New York—Atlanta acts like a magnet, attracting multiple Afrodescendant peoples from near and far, whether they’re from other regions of the South, settling in the South from the North, in a phenomenon counteracting the Great Northward Migration of the last century, or from the “new” Black migration of Africans, Caribbeans, South Americans, and Afro-Europeans making their way to the United States and Atlanta since 1965. This is how Atlanta has become a major home to the Black-African diaspora. Their mix is felt in a variety of ways here, from the city’s cuisine to its diverse vernaculars.

That is what I saw and understood in Atlanta.

That is where I heard the echoes of the Atlantic calling, and ringing out in Cascade—in Atlanta.