Afrofuturism at the Metropolitan: Encapsulating Art and History

Courtesy The Metropolitan Museum of Art - Photo by Anna-Marie Kellen

By Anne Lafont

Since November 5, 2021, the Metropolitan Museum of Art has offered an Afrofuturist period room to explore. In this new exhibition space, the imaginary and fantastical setting of an African American family’s New York home in a Seneca Village that was not razed to make way for Central Park is displayed. The space succeeds in crossing the convention of the period room with the inventiveness of Afrofuturism to renew the modalities of inscription of the patrimonial institution in the actuality of history.

Founded in the early 1820s by African American families, Seneca Village was located—just a short distance from the museum—in the forest that preceded Central Park. In 1857, the development project for this land (with its share of expropriations) was implemented by the city’s public authorities. The small, free Black community that made up the village–along with the immigrants from Germany and Ireland who had joined it–had to vacate the land, and in the fragmented process of relocations, their community dissolved. It is in response to this dark and chronic history of dispossession and loss that the conception for the period room at the Metropolitan Museum of Art was envisioned.

A team of curators, decorators, scenographers, and historians created this Afrofuturist room and apparatus, entitling it Before Yesterday We Could Fly: an Afrofuturist Period Room, in homage to the legend of slaves who narrowly escape by flying. Indeed, the conceptual and concrete pattern of fugitivity belongs to African-American theoretical culture. It is present in the works of Fred Moten and Saidiya Hartman, and covers the aesthetic strategies of resistance such as escape from the plantation and slavery’s expansive conditions. It is also found in traditional African American tales, as told by Virginia Hamilton in her 1985 collection The People Could Fly: American Black Folktales, which inspired the title of the installation.

The Black Vessel

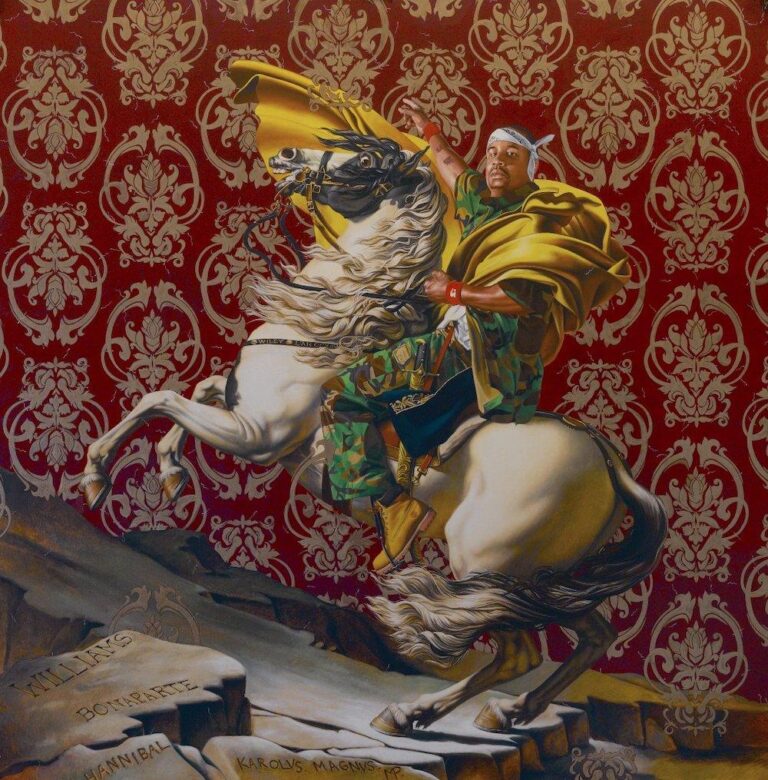

Afrofuturism is an artistic movement of many forms: the music of Sun Ra, the Black heroes of comic books and science fiction cinema like Black Panther, the performative work of the Kongo Astronauts, whose photographs decorated the walls of Paris during the first lockdown thanks to Dominique Malaquais’ exhibition Kinshasa Chroniques, and the novels of Samuel R. Delany. All of these works depict fantastical future times, whose particularity is that they supplement a painful Black history with a projection of a utopian Africa, both ancestral and unprecedented, traditional and high-tech. Afrofuturism is therefore a space for writing myths with historical anchoring and avant-garde imagination.

Since the 1970s, this artistic movement has responded to the need for modes and discourses, for stories that–in the absence of abundant sources that examine Black history– imagine it and manufacture it from fragments of the past. In the world of Black art, there is indeed a close link between the lack of archives and the proliferation of stories about the Black experience. Above all, the history of slavery has–and continues to–provide the present and the future with an emancipatory perspective. It operates, as far as Afrofuturism is concerned, through fictional installation and technical projection. Mark Dery is considered the inventor of the term Afrofuturism, which appeared for the first time in a book he edited and for which he had collected, among other things, a series of interviews with the authors Samuel R. Delany, Greg Tate, and Tricia Rose.

For the installation Before Yesterday We Could Fly, the curators called on some twenty African and Afro-descendant artists (including Willie Cole, Zizipho Poswa, Fabiola Jean-Louis, Roberto Lugo, Tourmaline, Atang Tshikare, Elizabeth Catlett, and Henry Taylor) and brought together a collection of historical pieces from the museum: a Congolese crucifix from the 17th century, an American rubber comb from 1851, and German rococo glass containers, decorative or functional objects included in the fantastical home of this invented Black family.

The weight of this new room within the museum is immense, like the institutional and public expectation encapsulated in this place dedicated to a mythical project. It evokes the failed history of the community and village neighboring the museum, inventing a period room meant to materialize, in a utopian way, a decorative era and world of African American history, and finally displaying contemporary Black creation. However, because it is a dwelling of modest size within a small exhibition space, this house is not a reconstitution, even an approximate one, of what the sources allow us to consider. Nevertheless, this imaginary African American home calls to mind an aesthetic of another time–past and future simultaneously–with the means of history: the map of the Seneca neighborhood–the only one known to date–is transformed into a wallpaper pattern; the fragments of Chinese porcelain and Venetian glass found during archeological excavations carried out in plots of territories once inhabited by Blacks, credit the presence of imported objects of great sophistication, including a Cameroonian decanter decorated with pearls, while a gray and blue jar by Thomas W. Commeraw, a mid-19th century African American ceramist, is among the precious dishware gathered in the kitchen.

The written and material sources of African American history, often few in number and poorly known, were the subject of in-depth research and care for this exhibition, and, if they’ve conspired the space and the project as a whole, it’s because they could only have been so grossly deployed for the immersive ambition of the period room to be achieved. However, the characteristic of these cabins that allow us to go back in time comes from the fact that their stylistic option relies on the most complete sensory illusion of a bygone era. Here, the concept gets complicated by the fact that the quest for this past era opens up to an imaginary future and consequently to a figurative space that is science fiction.

Thus, this fiction–more enchanted than scientific–also takes the form of a window into contemporary African and diasporic creation staged by a particularly rich curatorial proposal. Consequently, more than a reparation or a corrective–which are often poor compensatory responses in the face of art and history’s silences, to use the expression coined by Michel-Rolph Trouillot–the afrofuturist room acts like a cabinet of wonders revealing the creation (painting, ceramics, sculpture, video, textile…) of the presumed descendants, in the broadest possible sense, of the inhabitants of Seneca. Thus, the period room is above all a narrative space of African heritage and creativity.

Courtesy The Metropolitan Museum of Art – Photo by Anna-Marie Kellen

The machine room

Similar to an actual machine room, this period room also acts on the whole museum, like a wave transmitter passing through the collection and reevaluating the traditional history of art in regional schools. It sets stories based on an untimely cultural device that impacts the canonical history of art in motion. From then on, this story turns out not to be false or obsolete, but insufficient and, by this very fact, available for partly fictitious extensions.

The public attendance to this new room shows that museum enthusiasts cherish the idea of being disturbed in the routine of their lives, of being surprised by a temporal and stylistic disconnect. The viewer finds themself distracted from their routine contemplation but also exposed to the intensity of a microcosm that functions in contrast to the White Cube (modernist format of the stripped-down exhibition). The period room imposes itself from the start with extravagance, in an excess of objects, ideas, colors, textures, and references that put the viewer off balance, beset and worried by the sum of sensory appeals. In this sense, this period piece differs from the attempts at decorative reconstruction that sometimes pulsate the museum’s track record. The temporal undecidability of the Metropolitan’s new room adds to the disconcerting character of the traditional period room, because the viewer cannot call on their knowledge of other museum pieces from the period to register this strange place in a series.

Finally, by its format and its function within the museum, the Seneca house is also similar to a time capsule, insofar as it is made for future societies and included in heritage buildings, like the two boxes recently found at the foot of the statue of General Lee at the time of its removal (Richmond, Virginia, September-December 2021). At odds with the moment of the museum, the afrofuturist piece indeed exposes a cluster of signs and witnesses of future times, what could be defined as the material and artistic culture of black anticipation.

There is another singularity in the apparatus invented at the Metropolitan, that of the house inside the room; not only the imaginary room of a house whose walls blend with those of the museum, but a kind of dwelling built in the room of the museum, the walls of the latter being lined with a monochrome green wallpaper in the shape of a patchwork of patterns. Thus, there is a space reserved for the viewer, who enters the Seneca house only with their eyes, thanks to the windows and other doors reserved for this purpose. The establishment of this border, in other words of this liminal space of the sidewalk which surrounds and thereby encloses the house built in its center, is quite surprising. An enclosure, a passage, an exterior corridor: this is the viewer’s space, in the in-between that separates the museum from the chimeric house. How are we to understand this formal intensification of the border between these two places? And the need to isolate and cordon off the fantasized African American home which, contrary to the immersive propensity of period rooms, maintains its own space and only tolerates a visual incursion detached from the experience of the watching body? The paradox is difficult to explain and the visitor regrets, at first, the flattening of the experience by an inhibited wandering. But this encapsulation ultimately reveals itself to be properly afrofuturist.

Not only does the apparatus reference the segregation unique to American history, but we are also faced with a sort of spaceship still in the hangar. Finally, this afrofuturist house also echoes David Hammons’ 2007 piece Minimum Security. Although of opposite design, they both work the limits of the African American space within the museum, the belt and the strapping of the Black living space in an enchanted and utopian version at the Metropolitan, in a carceral and critical version for Hammons.

The brilliance of the curatorial team here was to cross the convention of the period room with the inventiveness of Afrofuturism to renew the methods of inclusion of the heritage institution in this present moment of history. This option is particularly appropriate today because it offers alternatives to the temptations of vandalism. The installation also conveniently echoes the redeployment and redesign of American art galleries of the 20th century with the exhibition of works by Sam Gilliam, Kerry James Marshall, and Amy Sherald, and thereby opens up to a more general questioning of the social role of the museum. This would fall under a double ambition: that of bringing a certain number of Black artists into the Metropolitan while confronting the long history of underrepresentation in the galleries and permanent collection of the institution. The room echoes the community pressure that has manifested itself in American public life since the 1960s, and which has experienced renewed deployment and conviction over the past ten years in response to persistent racist crimes. More than a band-aid or a nod to intense current events, the Metropolitan Museum of Art is creating the opportunity to reinvent the museum, to offer it the possibility of occupying a function that lies between the porousness of life in the city and, ultimately, an awareness of modesty as well as the need for critical and emancipatory means of art which enlarge our future.

Before Yesterday We Could Fly: An Afrofuturist Period Room, Metropolitan Museum of Art, Long-term exhibition-installation, November 5, 2021-…

By: Sarah E. Lawrence, Iris and B. Gerald Cantor Curator in Charge of the Department of European Sculpture and Decorative Arts, Metropolitan Museum of Art ; Ian Alteveer, Aaron I. Fleischman Curator, Department of Modern and Contemporary Art, Metropolitan Museum of Art ; Hannah Beachler, Lead Curator and Designer ; Michelle D. Commander, Consulting Curator and Associate Director and Curator of the Lapidus Center for the Historical Analysis of Transatlantic Slavery at New York Public Library’s Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture.

Anne Lafont is an art historian and director of studies at the École des Hautes Études en Sciences Sociales, where she is interested in the visual fabrication of race and the invention of African art in discourse and practice. She is a specialist in the representation of black figures from the Enlightenment to the modern period. She is currently a resident at Villa Albertine.