Democracy, cultural rights, and digital utopias

By Marie Picard and Emmanuel Vergès

Is the notion of Cultural Rights, which appeared nearly 80 years ago, still relevant in the age of the Internet? In this article, based on their intervention at the Night of Ideas in Atlanta, Marie Picard and Emmanuel Vergès place themselves at the intersection of cultural rights and digital cultures to envision a new cultural framework that is inclusive, open and sustainable. The stakes are high; it is nothing less than the possibility of democracy.

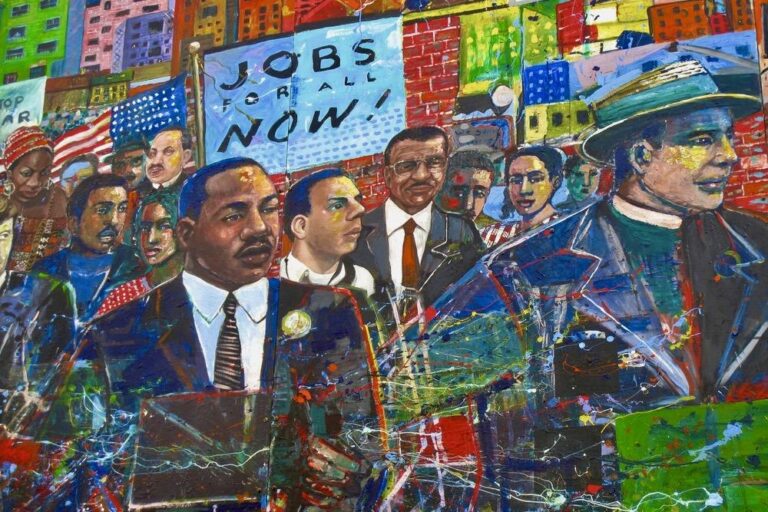

After World War II, a widespread civil movement emerged pushing for culture and education to be recognized as “tools” for strengthening democracy and ensuring that society would never repeat its recent atrocities. The notion of cultural rights was written into the 1948 Universal Declaration of Human Rights. They are described in Article 27 as the ability of individuals to participate in cultural life, as well as the right of each one of us to express ourselves, and to protect our works and productions. In keeping with the various decolonization and independence movements that have occurred since the 1950s, and with the US civil rights movement, international organizations like UNESCO have been working to promote cultural diversity as the common bedrock of human development (e.g. through the 2001 Universal Declaration on Cultural Diversity, and the 2005 Convention on the Protection and Promotion of Cultural Diversity). In 2007, a group of experts published a key text, the Fribourg Declaration on Cultural Rights, which aims to define and consolidate these rights with a view to enforcing them in our society. In Belgium and in France, this text has led to the drafting of several laws that have transcribed these rights within cultural institutions.

A global, digital-led society

Today, these rights may be seen as conducive to the current rapid evolution of cultural practices, the emergence of third places, and the notion of asserting the equal dignity of cultures as a concern of democracy. In a global, digital-led society, cultural rights are being implemented on the Internet and social media, as well as fablabs and makerspaces. Indeed, such tools and spaces are founded on principles that favor decentralized expression and collective, peer-to-peer production, which have profoundly transformed the ways in which we construct culture. Moreover, the Internet has become a major, universal tool of expression in our societies. Artists, citizens, and countless different communities have understood that this digital transformation constitutes a great cultural revolution. We have witnessed this with major movements, such as #MeToo and #BLM, and many other developments. These movements and changes show the extremely powerful impact of this contributive, far-reaching tool.

Together, cultural rights and digital cultures offer new perspectives on individual freedoms and collective challenges. We approach these cultural rights in a landscape of media and politics that includes new stakeholders, yet the Internet is not necessarily a tool that favors democracy, social justice, and ecology, however, given the emergence of multiple new problems for society. These include the attention economy, deregulation of the intellectual property and copyright framework, uberization of working practices, spread of disinformation, misuse of AIs, data security issues, taxation issues, and so on. Although it is digital in nature, this new landscape is, by definition, a public space that fundamentally challenges existing relationships between individuals, democracy, media, and culture.

In this text, we share two observations linking cultural rights and digital cultures in order to offer avenues of reflection that move away from a simple criticism of Big Tech, and to bring user and civic rights back to the core of the debate.

The limits of algorithms

Our first observation concerns social platform and social network algorithms. Social platforms and networks are our gateway to learn and share. But their algorithms come with limits and biases, replicating the norms and standards of their creators, who are most often affluent white men. Consequently, algorithms are becoming new models of cultural domination. How can we adapt them to respond to democratic challenges? A whole body of political and academic research has emphasized the importance of implementing regulations (GDPR, IA Act). As we see it, however, the response should not just be the concern of the legislative branch. Cultural rights, as a cultural approach to our relationships, allow us to conceive of algorithms as a space of collective cultural experience that can foster more democratic interactions with the media. By the same token, algorithms should not be considered as opportunities to commodify our attention or to develop a deeply asymmetrical, inegalitarian, and ecologically destructive model of surveillance capitalism.

Lest we forget, the original cultural vision of the Internet was to connect all points of the peer-to-peer network, and to foster a collective cultural experience. To quote Laurence Lessig, “intelligence lies at the edges” of the Internet. With our digital tools, each one of us has the means to receive and circulate content from any point on the network. We have moved on from the media pyramid and media ecosystem. But although we know how to make pyramid systems more democratic, we still have our doubts on whether democratic governance truly reigns within these ecosystems

One avenue of investigation on this subject can be found in Fred Turner’s The Democratic Surround (University of Chicago Press), which chronicles the history of the Committee for National Morale in the US. Working closely with the US government in the 1930s, this group of around one hundred anthropologists, artists, thinkers, reporters, etc., called for reflection on media’s democratic capacity as an alternative to propagandistic mass media. This capacity would emerge within media environments through consultation and individual content production, and the sharing of a common cultural and collective experience. This is consistent with John Dewey’s view of art as an experience, with the experimentations carried out at the Black Mountain College, and with the exhibitions that were held at Buckminster Fuller’s domes (REF). Turner believes that these reflections also served as a basis for designing the cultural and technical architecture of the Internet.

Online practices as unifying cultural rituals

Our second observation focuses on content and on what it constitutes as “the message of the medium,” to paraphrase McLuhan. Despite its massively prevalent use in today’s world, digital content is still largely overlooked as an example of cultural property, or as a method of prescription and cultural legitimization in our societies. But what, at its core, does all this content have to do with democracy? From the perspective of cultural rights, these thousandfold expressions are our new “common good.” Democratic issues are becoming fundamentally intersectional and must therefore consider all issues of discrimination and domination, such as those concerned with economic background, ethnicity, culture, gender, sexual orientation, and disability. These rights help us envision a new cultural framework that is inclusive, open, and sustainable. But how exactly?

One approach is to consider social networks as more than mere platforms of egocentrism and narcissism. Their content is, by definition, based on personification and contextualization between the subject and the author. We refer to this as the embodiment of the message. Messages gain their meaning from those who circulate them, receive them, re-share them, and so on and so forth. These messages can be repeated, imitated, deformed, contradicted, etc. All these forms of expression that we find online are creative rituals that append, link, reference, legitimize, and establish singular words as shared cultural experiences.

Hashtags connect us to the same situations and provide us with information. When we add algorithms to the mix, we are given new connections and new knowledge. While we scroll, post, comment, and connect, we accumulate new viewpoints in order to cultivate cultures. Posts, articles, and sites link our content from margin to margin, edge to edge, allowing us to express our identities and to recognize ourselves in cultural communities. The Internet has the potential to make the margins visible to all; to make us consider each margin with equal dignity. All this is constituent of our right to express ourselves, our right to know, and our right to practice and share. It is democracy in action!

By virtue of this content that expresses our practices—and the links that connect different forms of content and connect us to one another—the network is not only digital and immaterial, but tangible in the real world. Our shared content is translated into genuine cultural rituals, and becomes embodied in tangible reality while also embodying the network. We maintain that this content and these links constitute a ritual of sharing similar to those found in all cultural or social acts across the globe since the dawn of humanity, from weddings to welcoming ceremonies to dances, and beyond. Social networks bring a certain aura to our creative rituals, which enter the artistic realm through collective appropriation, and become enshrined as gestures that represent identities and communities. In this way, we move from individual expression toward community practice and cultural expression.

This vast digital space of cultural rituals empowers us to act when we scroll each morning on our smartphones.

A new democratic common good

In digital practices and environments, cultural rights are drivers both in proposing new frameworks for platforms and in helping us recognize that these practices are cultural rituals in their own right. These two concepts enable us to foster our democratic personas and shared cultural experiences. What we have here is a new vision of democracy that provides an alternative understanding of the link between the individual and the collective, along with new perspectives on the notions of freedom and community.

Individuals must be free to belong to various cultural communities, but they must also be able to switch from one community to the next throughout their lives in order to support their emancipation and drive social justice. The Internet helps consolidate and embody these principles by giving individuals the capacity to produce and circulate content, and thus to relate to each other freely. The challenge now is to define the purpose of these links, and what they produce in the exchange economy.

While Big Tech attempts to capture our data and exploit the unpaid work that we perform for them online, free cultures are creating new systems of cooperative production. On the Internet, cultural rights allow us to envision a shift from an attention economy dominated by a few giant corporations to an economy of knowledge or, indeed, of understanding that is led by all