Walking along Chicago’s Rivers

Ⓒ Jennifer Buyck

By Jennifer Buyck

Is the notion of landscape still relevant in an urban environment, especially when we talk about the city par excellence: Chicago? Architect and researcher Jennifer Buyck questions, at the age of anthropocene, the ways to renew the link between the living and the urban. It is by strolling along the river, camera in hand, that she investigated how it has played such an important role in the construction of the city, and how it could play an equally important role in the necessary ecological turn of the metropolitan construction.

I recently spent a month in Chicago, paying attention to urban ecologies. During this month I walked every day along the rivers that cross the city. The rivers are connected to Lake Michigan but their course was reversed at the end of the 19th century. In other words, the rivers have been flowing against the current for 100 years. The history of these rivers is intrinsically linked to the history of Chicago since its founding. Looking at them and revealing them is a way of making visible the environmental backdrop of the modern metropolis. By walking along the riverbanks and documenting this investigation through photography and video, I proposed to investigate the current ecological and social status of these rivers as well as their place in the metropolis and its future. In addition to these walks, I also met a large number of actors involved in the daily, scientific or prospective management of these rivers. I propose here a brief overview of these explorations.

Ⓒ Jennifer Buyck – Chicago Rivers Locks

This first image is a good illustration of my first day of investigation. In the background, we can see Lake Michigan, one of the five Great Lakes of North America, a gigantic reserve of drinking water at a global scale. Its shoreline, some thirty kilometers across Chicago, supports a vast network of parks and cultural and transportation infrastructures. In the foreground is the Chicago River, which, in contrast, is only minimally landscaped. It is rather a functional waterway. Between, we see the Chicago Harbor Lock, that is to say the lock that regulates the passage of boats but also that of water. Built between 1936 and 1938, this lock is part of a vast and complex system of canals, pumping stations and other locks whose purpose was to reverse the course of the river. The river, nicknamed “the stinking river” by the inhabitants, carried the wastewater of local industries including the gigantic abattoir where livestock from all over the United States was transported. Following the natural course of the river, this water then flowed into Lake Michigan, which is also Chicago’s drinking water reservoir. Epidemics of typhoid and cholera – and more generally the numerous sanitary problems generated by this situation – forced the local authorities to seek a solution. In 1900, this solution led to the reversal of the river’s course, which will now flow – artificially – into the Mississippi and thus into the Gulf of Mexico in the southern United States. This first image shows what was once the mouth of the river and is now its source. What relationship can the city and its residents have with a river that is so much an artificial infrastructure and that crosses the metropolis from one end to the other over some 274 kilometers?

Ⓒ Jennifer Buyck – Main Stem

When people think of the Chicago River, this is often the image that comes to mind. It is the Main Stem, the river that runs through Downtown and its skyscrapers. For approximately three kilometers, the banks of the river have been transformed into a promenade for residents and visitors. The river is here a central element of the scenarization of the vertical city. But it is in fact a very small part of a much larger hydro-social system organized around the Chicago and Calumet rivers. It is this entire system of rivers in Greater Chicago that is now flowing in the opposite direction, not just Main Stem. What types of riverfront design exist outside of Main Stem? For what intensity and purpose? Every year Main Stem is colored green for St. Patrick’s Day. This tradition, which began in the 1960s, is now subject to debate. Illegal colorations have been observed in recent years in the upper – much “wilder” – portion of the North Branch of the Chicago River. For the Friends of Chicago Rivers, this is going a bit too far: “Imagine fish, beavers or otters swimming through that dyed-green water”. While water quality and ecosystems have significantly improved, could we not stop perpetuating the idea that this waterway is polluted? Shouldn’t we invent – collectively – another relationship with the river, another way of living with the river? And on what basis? This is the question that drives me when I walk.

Ⓒ Jennifer Buyck – Chicago Portage National Historic Site

To briefly introduce the river system, I will say that there are three main rivers: the Chicago River to the north, Calumet to the south and Des Plaines to the west. Only the Des Plaines River follows its normal course. The other two have been reversed. In between there is a series of canals and dams that make all these rivers converge. In the past, it was by carrying a canoe over a couple of kilometers of swampy land – like those of the historic portage site – that it was possible to connect the rivers and thus reach the Mississippi from the Great Lakes. This is how the first explorers of the continent, but especially the first Native American inhabitants, reached the Mississippi from Lake Michigan. It is this proximity between the hydrographic system of Lake Michigan and that of the Mississippi basin that is at the origin of the foundation of Chicago, a city of passage between two universes with complementary riches. The growth of the city of Chicago is based on the redesign of these rivers. This was done not only by changing the direction of the current and renewing the layout of the river beds, but also by leveling and draining the hinterlands. While Chicago was built on a wet, swampy plain with winding rivers, there is little swampland left today. When we consider the city’s difficulty in managing its stormwater – a challenge accentuated by climate change – we can only regret this large-scale land artization.

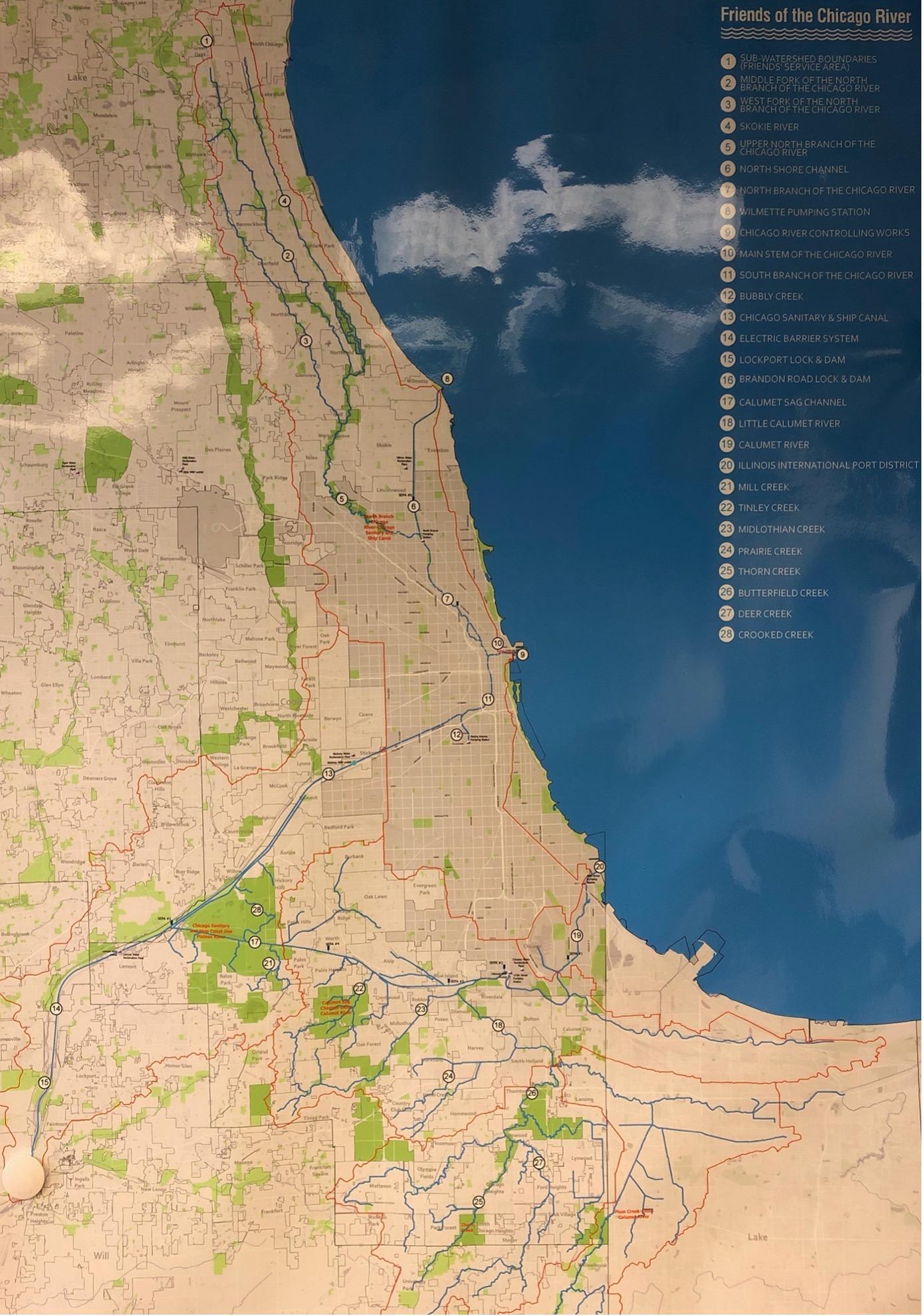

Friends of the Chicago Rivier – Chicago River Map

Chicago’s sewage and rainwater are discharged into rivers, except in Des Plaines. Before 1900 it went via the rivers into the lake, since then it all flows through the city into the Mississippi and finally into the Gulf of Mexico. Gigantic, modern sewage treatment plants treat this wastewater before it is discharged into the rivers. One of them is the largest in the world. Nowadays, in case of heavy rains, the sewage system is saturated and discharges into the rivers without any preliminary treatment. This issue was raised repeatedly during the interviews. And these heavy rains are becoming more and more frequent with climate change. Begun in 1974, the Tunnel and Reservoir Plan (TARP), or Deep Tunnel, is a system of large-diameter deep tunnels and large reservoirs designed to reduce flooding, improve water quality in rivers, and protect Lake Michigan from pollution caused by sewer overflows. In a sense, it doubles the river system and follows its path. It is the new hinterland, in a way. The TARP captures and stores the combined stormwater and wastewater that would otherwise overflow the sewers during rainy periods. This stored water is then pumped from the TARP to water reclamation plants to be cleaned before being discharged into waterways. But it’s hard to talk about TARP in the present tense because Phase 2 of the system won’t be in place until 2029. Some people say, however, that this system will be obsolete before it is completed. Couldn’t a large-scale soil remediation project be considered as a complement? It is easy to imagine how renaturation of the initially wet land could have a very positive impact not only on rainwater management but also on biodiversity and the reduction of urban heat islands.

Ⓒ Jennifer Buyck – Chicago River et North Shore Channel à Robert Park

The North Branch of the Chicago River and the North Shore Channel meet at Robert Park on Chicago’s north side. This is just one example of the renaturation of the river and its banks. If the photo had been taken in 2018, it would have shown a dam crossing the entire image. Requested as early as the 2000’s, the removal of this four foot high concrete dam (about 1.20 m) was approved and completed by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers. The dam was built in 1910 to compensate for the difference in water level between the North Branch of the Chicago River and the North Shore Channel, caused by the reversal of the Chicago River a decade earlier. Today, the dam has been replaced with riffles that slow the flow of water and open a passage for fish to swim upstream. But that’s not the only improvement to the River Park. Native plants and wildflowers have gradually been reintroduced along the banks. Army engineers are working here to restore ecosystems. Further along, local residents are doing their own renaturation of the riverbank. Other projects, such as the Wild Mile Chicago, are also part of this dynamic, that of the renaturalization of rivers and potentially that of the renaissance of the great river system of the metropolitan area. I wonder, however, to what extent the accumulation of these local projects will change the system as a whole?

Ⓒ Jennifer Buyck – Riverbank Neighbors Park en face de Horner Park

Here is a riverfront landscaped and appropriated by the residents. It is a linear park with a path along the water and plantations in terraces. The whole paved with stones here and there. It is here the methods of ecological management of the place which arouse my interest. A sign at the entrance of the park tells us that spring is the right time to carry out a prescribed burn of the river banks. Permits have been granted and people trained and experienced in conducting burns will be coming to the site. According to the sign, fire is necessary to maintain the health of ecosystems. Fire suppresses weeds. It reduces thatch accumulation and allows native seeds to germinate. Fire also darkens the soil and warms it in the sun. And the resulting ash releases nutrients for plants. Healthy grasslands also store huge amounts of CO2 in their extensive root systems. Burning is done when the weather conditions are such that they maximize the success of the burn and minimize the inconvenience. This is not the first time I have seen this technique in the United States. It seems to me, in comparison, to be very little used in France. Applied on the scale of shared gardens but also on the scale of vast natural reserves as in the Indiana Dunes National Park for example, this technique arouses my curiosity. It deserves further investigation as it challenges the way we have in France to consider the sustainable management of natural areas. On the other hand, this place also invites me to think about the place and the role of the inhabitants in this new relationship with the river. I note that here the notion of volunteers often comes up. Where in France we speak of participants. This difference seems significant to me.

Ⓒ Jennifer Buyck – LaBagh Woods

The river here gives the feeling of being natural – and that’s as it becomes supernatural… Let me explain, we are here in LaBagh Woods. Located on the Upper North Branch of the Chicago River on Chicago’s Northwest Side, LaBagh Woods features a variety of natural areas including wooded landscapes, wetlands, savannahs and sedge meadows. Known for its outstanding birding opportunities, LaBagh Woods is at the southern entrance of the popular North Branch Trail System, an approximately 20-mile trail system connecting Chicago to the Botanical Garden located in Glencoe. I walked this trail. I was very surprised by the potential for disconnection that these places offer. It makes you feel like you’re outside the metropolis. Moreover, the dissociation between water and soil is no longer obvious. The area around the LaBagh Woods and the Upper North Branch was important to the Native Americans. The river itself would have been a great resource due to its proximity to the greater region, a vast landscape dominated by wetlands and at the intersection of grasslands, woods, and the Great Lakes. Which means it was certainly a very good place to live. Walking along these marshes and this patchwork of landscapes hemmed in by rapid urbanization, it is hard not to think that the rivers were once the site of other ways of life. Those of men and women whose relationship to nature was different. Those of men and women who were constantly pushed back a little further. The rivers are here the witness of what could be the pre-colonial landscapes and they bring us more widely to reflect on the close relations which can unite environmental and social justice.

Ⓒ Jennifer Buyck – Rowing on Bubbly Creek

My exploration of the South Rivers begins along the South Branch of the Chicago River. The more I move away from the center, the more the banks become industrial. I face large factories, storage areas for equipment, gigantic warehouses. But the reconquest of the riverfront is underway. Here is an example. It is the rehabilitation of the mouth of Bubbly Creek, one of the forks of the Chicago River. Two kilometers long, Bubbly Creek – literally the creek that makes bubbles – is a link between the Chicago River to the North and to the South the huge area that was until the 1970s dedicated to slaughterhouses. From the Civil War until the 1920s, more meat was processed in Chicago than in any other place in the world. This gives you an idea of the size of these slaughterhouses where livestock from all over the country was transported by train. These gigantic stockyards are considered as the paradigmatic expression of the animal-industry relationship in its modern form. In his novel The Jungle (1906), the writer Upton Sinclair describes the unhealthy and inhumane working conditions in which the workers of the American meat packing industry worked. Bubbly Creek got its name from the gases that escaped from the riverbed as a result of the decomposition of blood and entrails that were dumped there in the early 20th century by the Union Stock Yards. Today, cleanup operations have taken place and a new perception of the place is slowly beginning to emerge. Much has changed since Jeanne Gang’s architecture and planning studio published “Reverse Effect: Renewing Chicago’s Waterways” 10 years ago. But there is still much to do as well. The accompanying photograph is perhaps the most emblematic project of this new life for rivers. It shows a dense residential neighborhood along Bubbly Creek with rowing on the river – a sport that Chicagoans, especially college students, but also veterans and people in remission from cancer, are very recently beginning to take up. Not far from there, a Rowing Club has also been built. The whole is a Studio Gang project.

Ⓒ Jennifer Buyck – South branch depuis Ping Tom Memorial Park

This project should not obscure the fact that on the south side of Chicago the rivers are still very industrial and almost inaccessible. It is there that future large urban developments are taking place. But there is no real overall coherence. These are development zones led by private actors whose objective does not necessarily serve the common good of the city as a whole. However, these are gigantic pieces of cities that are being built and the public actors are struggling to make themselves heard as a counterpoint. Who will be able to ensure equal access to the river? In this context, the question is who will ensure the right to the river and what about the rights of the river? The image above shows one of these new urban expansion zones. It is south of Downtown and north of Chianatown. When I took the picture I was in the Ping Tom Memorial Park with its many Chinese features. At the edge of the park, I saw a vacant lot and I noticed a construction crane just a few steps away from this peaceful haven. Under the charm of the place, I thought ” maybe the park will be extended to be connected to Downtown “. It is actually the opposite that is happening. From my understanding of the project, it is Downtown that is being extended. The new district, named 78, claims to be “a World-Class Entertainment Destination”. It is an entertainment district with the future Casino at its heart: ” This compelling destination will leverage the best of Chicago’s entertainment and culinary heritage with new and unmatched experiences for residents and visitors alike.” I have some doubt that this is what Chicago needs. At least, it’s not exactly how I would have imagined an “inclusive” and “resilient” riverfront project. Unless we consider Disney Land Paris to be so for the Marne.

Ⓒ Jennifer Buyck – Co-construction of a walking route around Calumet River

In conclusion, I would like to return to the question that drives me. The river played a central role in the foundation and growth of the city of Chicago. Will it play such an essential role in the future? Under what conditions will it be central to the ecological turn of the metropolitan construction? At present, it is a vast and entirely artificial hydrographic system that essentially serves as technical backdrop to the built and inhabited metropolis. If we can now see that urban reconquest is underway, I also observe that it is very fragmented and is not based on an overall programmatic vision – and notably an ecological one. However, I am convinced that the rivers here remain a formidable potential for a collective and democratic project that can achieve the environmental metamorphosis of this modern metropolis.