An Interview with Jeffrey M. Leichman

Interview

Jeffrey Leichman (center left) and Benjamin Samuel (center right) present the foundations of social physics for VESPACE © LSU & Partners

By Jalalle Essalhi & Camille Jeanjean

The rise of XR technologies in Louisiana comes from pioneers like Jeffrey M. Leichman, Associate Professor at Louisiana State University.

About Jeffrey M. Leichman: Jeffrey M. Leichman is Jacques Arnaud Associate Professor in the Department of French Studies at Louisiana State University. Professor Leichman’s research focuses on theatrical culture from the early modern period through the present, with three main areas of concentration: early modern European and colonial performance; immersive digital humanities; and performance in cinema.

Your Interactive VR Simulation “VESPACE” is NEH-funded. Could you tell us more about the project? And how would you assess the public policies to support immersive creation in Louisiana and the US?

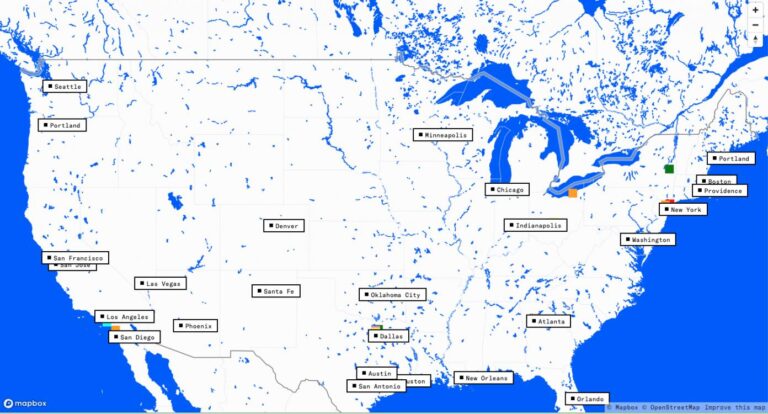

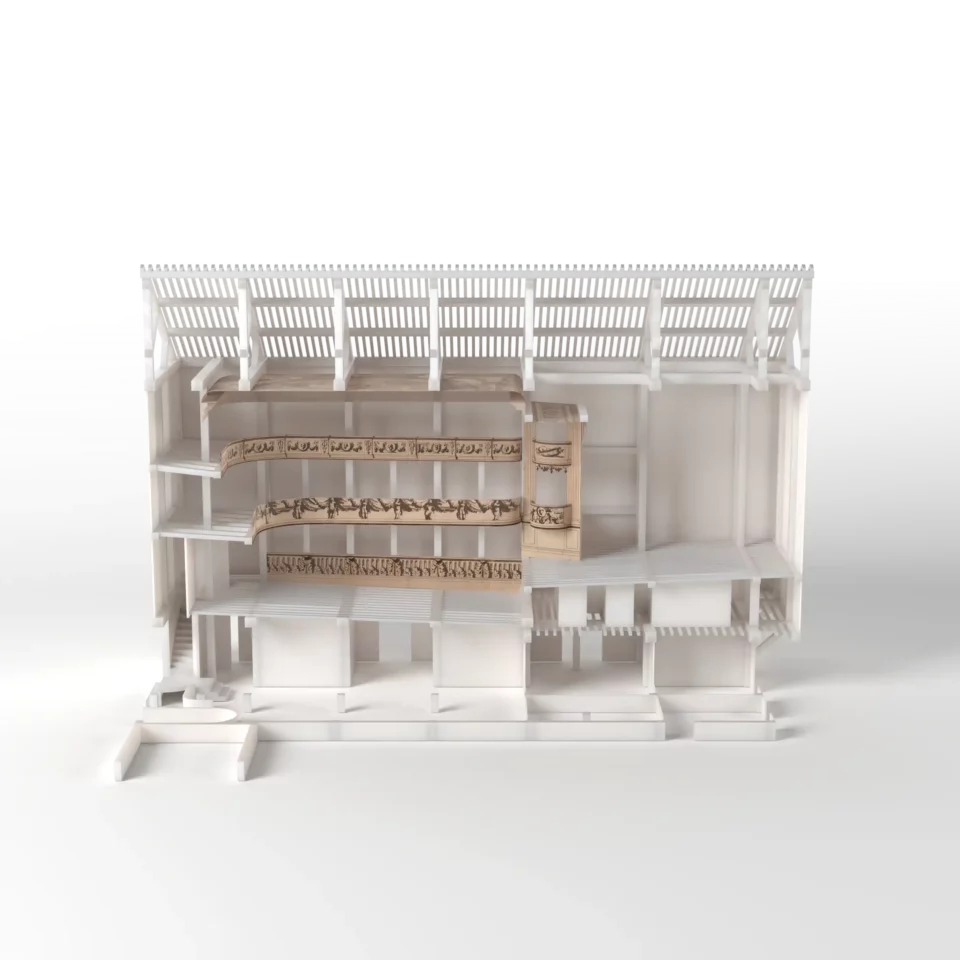

I can’t really speak to the situation in Louisiana, but I can speak to my own research. I was PI on a VR modeling and simulation project, VESPACE, a six-year collaboration with researchers in the US, France and England that was twice awarded grant funding from the National Endowment for the Humanities Office of Digital Humanities, as well as crucial support for a 3-year PhD studentship in France co-funded by Ouest Industries Créatives. As part of this work, I hosted two international meetings on the LSU campus in 2017-2018, and worked closely with colleagues at the Université de Nantes (notably professor Françoise Rubellin) and the Ecole Centrale de Nantes (notably professor Florent Laroche); our doctoral student, Paul François, earned his degree from both institutions, and his work on developing the architectural model for our interactive playable experience of an eighteenth-century marionette theatre was an important part of his dissertation (he is currently a research engineer with the CNRS in Aix-Marseille).

On a scientific level, our work with immersive technology was motivated by the historiographic lacunae around eighteenth-century Fair theatre, which suffers from both ideological and documentary shortcomings: ideologically, inasmuch as the traditional historiography of Paris theatre before the Revolution is limited to the Comédie Française, the Opéra and the Comédie Italienne, as designated by regulations promulgated by the crown; but this was largely an administrative fiction, as Fair theatre was an important artistic and popular phenomenon at least from the time of the 1696 expulsion of the Italian theatre (re-invited by the Regent in 1716). The crown was successful in projecting a top-down vision of unity on the culture of the capital, whereas research in the past twenty years (led in large part by Professor Rubellin and the CETHEFI lab) has revealed the degree to which Fair theatre were successful competitors and artistic innovators through the time of their merger with the Comédie Italienne to for the Opéra-Comique in 1762. On a documentary level, the administrative persecution of the Fair theatre (frequently pursued in court for infringing on the privileges of one or more theatres) has meant that the kinds of complete, well-organized documentation about expenses and income that characterize the Comédie Française, for example, are nonexistent. Researchers, working patiently in archives, have assembled a wealth of documents around the artistic and economic practices of these theatre, but their purely discursive nature, their widely dispersed locations and their fragmentary coverage make the work of understanding this culturally vital theatre quite arduous. To correct for this, we felt that a sensory-immersive model that allowed users to access information regarding the sources used to construct it would be an appropriate way to accelerate understanding of, and interest in, the Fair theatre.

Longitudinal cross-section of a theatre model by Jacques Cellerier for the Saint-Germain Fair from 1772 © Architectural rendering by Paul François

A summary explanation of the Fair theatre can be found, along with a great deal more information on this project, on our project website.

In terms of support, the NEH (a federal agency) continues to offer its Digital Humanities Advancement Grants, which offer three levels of funding, according to the needs of the proejct. This having been said, it is still the responsibility of researchers to line up their partners, and often the greatest challenge for humanists is securing collaboration with capable and interested experts in computer science and graphics. In our case, the technical work was split between the French team (architectural modeling and in-model information system) and the Louisiana team (game design and mechanics), led by Professor Ben Samuel at the University of New Orleans. In my opinion, this collaboration between public universities in South Louisiana shows a promising way forward for developing complex immersive projects, as is also illustrated in the NASA digital twin collaboration between LSU and UNO.

VESPACE team members outside of Hodges Hall on the LSU Campus, Baton Rouge, LA (l to r) Jeff Leichman, Françoise Rubellin, Arianna Fabbricatore, Mylène Pardoen, Florent Laroche, Paul François, Pannill Camp, Jan Clarke, Ben Samuel, Isabelle Duval © LSU & Partners

What about the hybrid virtual-live “1805” project?

From 2020-2022, I co-directed the Transatlantic Research Partnership (formerly Thomas Jefferson Fund) project “Virtual Theatre in the French Atlantic World: Urbanism and Spectacle, 18th-19th centuries” with Pauline Beaucé at the Université Bordeaux-Montaigne. In the course of my research for our project, I discovered the 1805 prospectus for a theatre proposed by Jean-Hyancinthe Laclotte, an architect from Bordeaux, for a massive theatre to be built own the Mississippi waterfront of New Orleans shortly after the Louisiana Territory was purchased by the United States from France. Working with New Orleans-based architect Shea Trahan, we designed a VR model of this theatre which we presented at the conference that concluded our project activities in December 2022; this work is currently under review for publication.

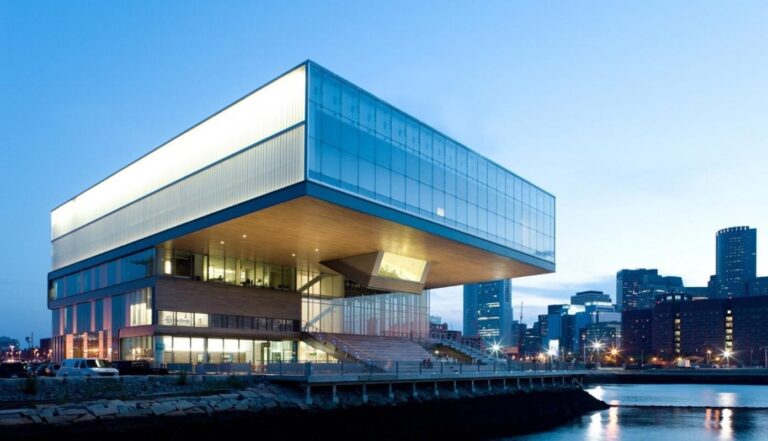

Mr. Trahan, the Director of Design at MADE in New Orleans, is also a Doctor of Design candidate at LSU, working on a thesis project around acoustical modeling for architecture. In collaboration with Jesse Allison, Associate Professor of Electronic Music at LSU, we have devised a project to allow concert-goers to experience the auditory restitution of a theatre that was never built. The DMC theatre, which is equipped with a 92-channel audio system, allows us to virtually shape the sound to transport listeners to different spaces.

The 1805 concert itself, scheduled for September 26 & 27, 2024, will draw on the repertoire of famed mixed-race singer Minette, who Feld Saint-Domingue at the time of the slave uprisings in 1791, an finished her life in New Orleans, dying there in 1806 just days before she was to perform in a benefit concert for herself and her large family at the Saint-Philippe theatre. This concert is doubly virtual, acoustically restituting both a space that was never built, and a performance that never took place, affording listeners an immersive experience of an under examined period of the region’s cultural history. As director of the Center for French and Francophone Studies (a member of the Centers of Excellence network designated by the Cultural Services of the French Embassy), I have been directing a project in which undergraduates are building a database of theatrical performance during the Territorial period of New Orleans (1803-1812), when a vibrant French-language theatrical scene played a vital role in perpetuating French culture during this first period of Americanization. Results of this work will be part of the lobby display outside of the 1805 concert, in order to showcase the project’s foundation in technologically mediated historical research. There will also be two lectures from scholars prior to the performance on September 26, on the Antillean origins of American blackface performance, and on the late-eighteenth/early-nineteenth century French comic opera repertoire.

In general, Louisiana being considered a cultural mecca, how would you describe the place and dynamism of digital in creative work and scientific/academic research? What areas for improvement do you see? and what would be the levers for action?

One of our project goals is to extend this consideration of Louisiana’s rich cultural history into a period that has generally received less attention than other times; while the antebellum (1820-1860) period is extremely well-known, and the post Civil-war period is the subject of intense examination, this foundational period when Louisiana was still culturally French but politically seeking a way to integrate into the American union – a period I like to call “Françamérique” – offers a rich field of exploration of how the region’s unique hybrid identity developed.

Louisiana’s cultural richness provides a wealth of opportunities for innovative applications of technology to humanities projects. Unlike in France, however, research units are not organized around laboratories that might ave research engineers attached to them who are available to provide technical support and active participation in a variety of projects. Instead, each research project must constitute its team anew every time. Some kind of permanent, shared structure that allows for research engineers to have a recognizable status and job security in order to provide support across multiple initiatives – as is the case at some very wealthy universities in the US – would be a huge stimulus to developing innovative digital humanities projects, especially in the modeling and simulation fields that I have been working in for the past 7 years.

Economists mention a technological barrier that is currently preventing XR technologies from becoming widespread. Given that the equipment rate is not yet important, what do you think could facilitate their development? Conversely, do you believe it is inherently a niche industry? especially with regards to the economic situation in Louisiana?

I’m not entirely sure that I understand this question, but I will say that in terms of VR applications that I have worked with, I think that the hardware component continues to pose a barrier to widespread adoption. Headsets are heavy, controllers are awkward, setup is non-intuitive and the required graphics capabilities mean that most ordinary (non-gaming) computers are inadequate to the task of running rich, interactive applications. While technological advancement may solve this issue (things are improving all the time!). On a more fundamental level this technology is currently very isolating and atomizing – the single user is closed off from the real world, in order to facilitate the experience in the virtual world. For this reason, projects like “1805” are quite appealing, as they allow for a communal experience of a virtual (or extended) reality – in this case through acoustical modeling. I think that thinking through these important problems of building community around XR/VR – not necessarily limited to community in virtual space – will be important for developing truly widespread adoption of this technology.

Scott Sanders (left) comments on a student's progress through the game, while another student plays on a different machine © LSU & Partners