The roots of border art

Aude-Emilie Judaïque

By Aude-Emilie Judaïque

From traditional Mexican art to contemporary border art, let us look back at Art History at the US–Mexico border. Frida Kahlo and Diego Rivera have given their fingerprints, Mexican muralism left its mark here. The voice of Chicanos still resonates. Today’s border artists are walking in their footsteps, like walking a tightrope between two countries held together by force. Is passion possible in a marriage of convenience? Will they turn divides into hyphens? French author of documentaries Aude-Emilie Judaïque explored the border as part of her Villa Albertine residency to answer these questions.

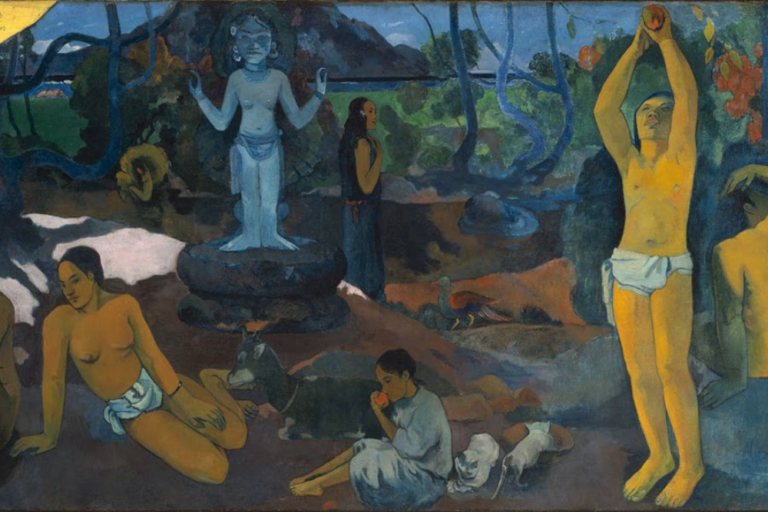

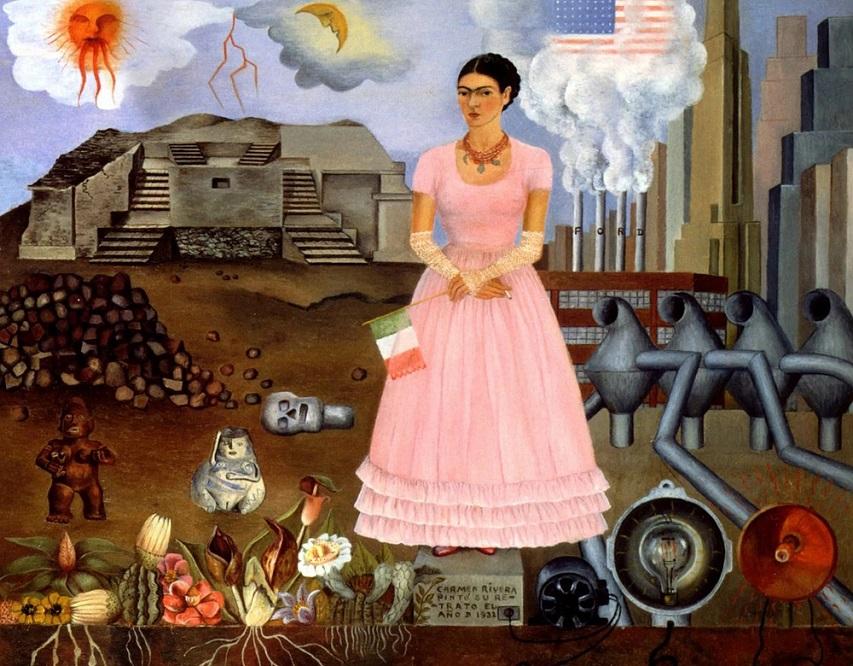

In December 1940, Frida Kahlo met up with her ex-husband, Diego Rivera, in San Francisco and married him for the second time. The famous, stormy couple of artists, both ardent champions of the Mexican Revolution, had already lived in the US but Frida did not like the country, depicting it as a capitalist society that destroyed human values. In her work Self-portrait on the Borderline between Mexico and the United States, which she produced in 1932, she portrayed herself in the middle of the painting like an uprooted rose, just hanging there unattached. To the left of her is all the energy, vitality, and fertility of her homeland—a host of objects from the pre-Columbian era and Mexican culture forming a matrix where all is tied together and interconnected: life and death, night and day, Mother Earth and Father Sky. Frida Kahlo was proud to be an heir of this Amerindian cosmogony and civilization, which ran through her pictorial style and, above all, forged her identity and political convictions.

In the right-hand corner of the painting, Frida depicted the United States, where she had reluctantly joined her husband. This area of the painting is clogged up, filled to the brim with factories, skyscrapers, machines, and pipes rising up in a lifeless, soulless world. Roots have turned into electricity cables, smoke has sullied the air, and concrete has suffocated the–now barren–soil. Here Frida Kahlo traces a clear-cut border between two contrasting, irreconcilable worlds.Here or ther, one has to chose: it’s one or the other. Her body is stiff like a fence post, her gaze stony. The border runs through her; it seems to pierce her like that iron rod did in a bus accident she underwent that left her disabled for life, without any hope of having children. In fact, during her time in the US, she had several miscarriages. Frida’s gaze and heart are resolutely turned towards Mexico. However, having left the US and divorced Diego Rivera, she is back to San Francisco to marry him again. There are borders that call out to you, obsess you, and run through you—for better or worse.

Self Portrait Along the Boarder Line Between Mexico and the United States, 1932 by Frida Kahlo

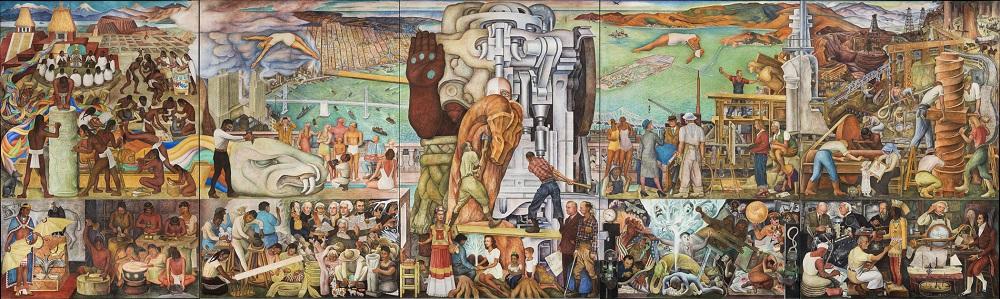

In that same month of December 1940, Diego Rivera finished a monumental work commissioned for the Golden Gate International Exposition (GGIE) on Treasure Island. He had already been commissioned to produce a mural a few years earlier, in the lobby of New York’s Rockefeller Center—an architectural masterpiece of prewar America. Unlike Frida, Diego was fascinated by the US and the industrial progress and modernity of this land he wanted to make his adopted country. He wanted to promote cultural and artistic exchanges beyond the US–Mexico border, even beyond all borders.

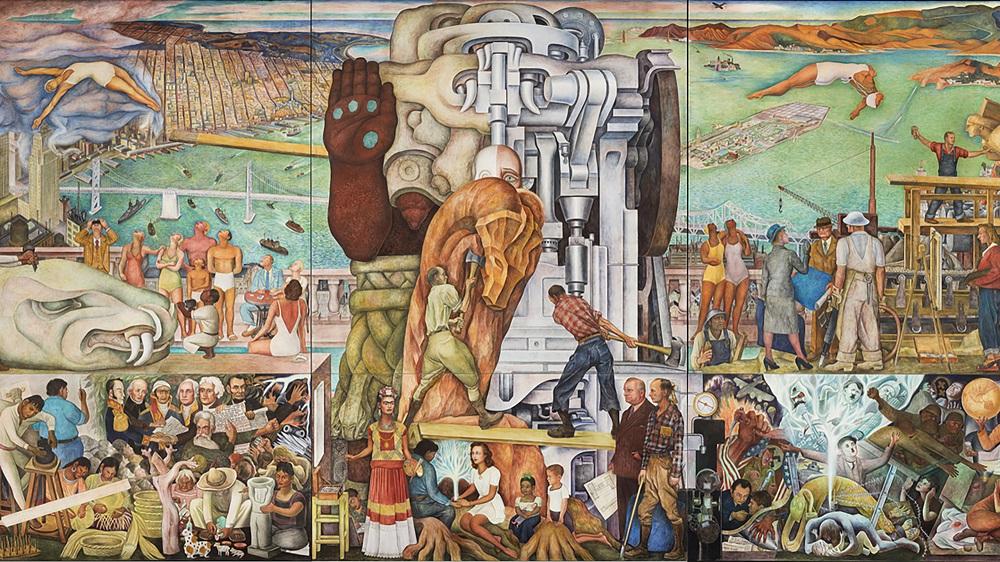

So he decided to paint an enormous mural in the best tradition of Mexican muralism to celebrate the “Marriage of the artistic expression of the North and the South on this continent.” The work is commonly referred to as Pan American Unity. It shows a union of two cultures, two artistic traditions, and extols the creativity and inventiveness of artists and artisans all over the Americas. “I believe in order to make an American art, a real American art, this will be necessary, this blending of the art of the Indian, the Mexican, the Eskimo, with the kind of urge which makes the machine, the invention in the material side of life, which is also an artistic urge, the same urge primarily but in a different form of expression.”

Diego Rivera, The Marriage of the Artistic Expression of the North and of the South on This Continent, also known as Pan American Unity, 1940

The mural’s two end panels mirror each other. The far-left panel, entitled The Creative Genius of the South Growing from Religious Fervor and the Native Talent for Plastic Expression, evokes the indigenous roots of Mexicans, descendants of the Maya, Aztec, and Toltec civilizations: Rivera showcases the Meso-American art, culture, and mythology of the continent’s indigenous peoples. The panel at the mural’s other end is entitled The Creative Culture of the North Developing from the Necessity of Making Life Possible in a New and Empty Land. It praises the endeavors of those pioneers who came from Europe to conquer and develop the continent of America. The panel pays tribute to innovation and engineering in the industrial age.

This mural, which abounds in symbols and references, is designed to draw our attention to its center, where Rivera placed a strange, imposing sculpture that enjoys pride of place, towering majestically with what appears to be a message of peace and wisdom. The sculpture depicts Coatlicue, the Aztec Earth goddess of life, blending into a soil-fertilization mechanism: an auto plant stamping machine. In this way, the hope of a union—even a fusion of the south’s spirituality and the north’s technology—is given concrete form. Contrary to Frida Kahlo in her Self-portrait on the Borderline between Mexico and the United States, Rivera presents the border as a place of exchanges and encounters, where anything is possible.

In the background, above the waters of San Francisco Bay, two women divers fly through the air—they seem to be able to swim and sail naturally from one world to the other. With the recent construction of the Golden Gate Bridge, the mural expressed the idea of a gateway linking the north and south: Rivera was convinced US–Mexico cooperation would ensure prosperity for both countries. He believed in this sacred union.

Through Pan American Unity, the Mexican revolutionary gave voice to his desire for a new dawn, for one “United people of Americas”. He espoused the La raza cósmica theory José Vasconcelos expounded in 1925, according to which the Americas would be a land where the world’s four races—African, European, Asian, and Amerindian—would merge into one. In his humanistic, universalist ideal, Diego Rivera saw America as a model, the first step towards this unstoppable global melting pot.

Diego Rivera, Detail of "The Marriage of the Artistic Expression of the North and of the South on This Continent, also known as Pan American Unity", 1940

But Frida did not see America in this way. On the contrary, she feared the confrontation between Mexican and US cultures and she was critical of Native peoples being forced to unite with newcomers. She stood up against the land grab by Anglos, the erasure of Indigenous ways of life, and the imposition of a Western imaginary. Her paintings focuses on the damage the colonization has caused, and the ruinous effects of capitalism, extractive industry, and intensive farming. It underscores that scientific progress can also spread death and desolation… And it stresses that a happy marriage requires two parties that respect each other, listen to each other, and accept their differences. For Frida, the relationship between the US and Mexico was too lopsided to bring any good.

Hope into cultural mixing or fear of civilizational change? As a couple, Diego Rivera and Frida Kahlo both perfectly illustrated the ambiguity of the border: it’s a places of friction and tension that sometimes turn miraculously into a bridges. So a border ran between the duo, in each of their paintings, between their paintings; between an optimistic and pessimistic view of the past and future; between a male and female view of fertility—including artistic fertility; between a positive and negative view of mass movements of peoples—whether in colonization or exile. Side by side, these two paintings express the full complexity of borders and the difficulties of migration, integration, and assimilation as Diego, Frida, and so many others experienced them.

Frida Kahlo and Diego Rivera got married for the second time in December 1940, but in the mural celebrating the “Marriage of the artistic expression of the North and the South on this continent,” which was completed in the same month, each artist has their back turned to the other. Rivera is planting the Maya liberty tree, hand in hand with Paulette Goddard, Charlie Chaplin’s wife. In his mural, he highlights a quote from Thomas Jefferson, the main author of the Declaration of Independence: “The Tree of Liberty must be refreshed from time to time with the blood of patriots and tyrants.” Liberty demands sacrifices, even here in the country that hoisted it up as a symbol for the world to see. To marry Diego again, Frida had to abandon her values and ideals: marital fidelity. Rivera, for his part, had to abandon the idea of emigrating to the US and the hope of living in a country at peace: in his mural, he urged the American giant to go to war against totalitarian regimes and defend Europe against Nazi Germany, which was allied to Stalin’s Russia. War is the price of Liberty—borders are its scars.

In their own way, Kahlo and Rivera embodied this border. The couple would never stop clashing and splitting up, walling themselves up in their own way of thinking. Yet each of them was unable to live without the other person or move forward in life without his/her support. Their lives and works illustrated their co-dependence, their co-existence through thick and thin. A border is a marriage of convenience, set up for stability and to bring peace to what was hitherto a front line. It is a fissure turned into a stitch. It is a scar—like those that covered Frida’s wounded body, and those that run through the whole of Mexican society—because borders do not disappear it they may shift or fade, but they it lasts, both on land and in memories. Borders become ghost lines you can play with. Frontiers you can even celebrate to in order to exorcize them, like in the Mexican Día de los Muertos (Day of the Dead).

When Diego married Frida for the second time and produced this mural of a pan-American marriage, he was not seeking to wipe out the border, but to rise above it and to overcome it. In his mural, he made sure to widely illustrate the military and deathly representations associated with the border, but also tried to break this mold and breathe new life into it. Imagining the border as a lifeline, a source of life, embodied by a fertilized Earth goddess. Rivera opened up a path to a reconciled society.

Through its symbolism, Pan American Unity meets all the political, esthetic, and educational aims of Mexican Muralism: according to this art movement that emerged in the early twentieth century, paintings should be produced outdoors in the streets so that all Mexicans, most of whom were illiterate and ignorant of their history, could understand them and the stories they tell. Through Muralism, walls would therefore speak and take on revolutionary significance.

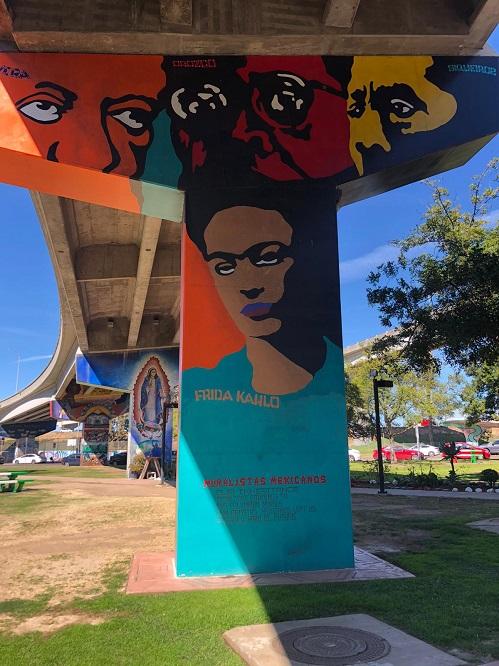

Since then, muralism has never stopped growing in the US: the Chicano Movement has brought it to the artistic forefront. Chicanos are Mexicans who became “foreigners in their own country” when, in 1848, Mexico lost its war against the US and half its territory*. When the border shifted, people who occupied this land unwittingly became Americans overnight. The same frontier continues to demarcate the two countries, and this trauma still haunts Chicanos. They are too often confused with Latinos, who came later to look for a better life in the US. In contrast, Chicanos never crossed the border—the border crossed them. 80,000 Mexicans (20% of the population back then) lived in an area that corresponds to present-day California, Texas, Nevada, and Utah, as well as part of Arizona, Colorado, New Mexico, and Wyoming.

Mexican–Americans were born of this marriage of convenience, forming in-between people, torn between a native land that no longer recognized them and an adopted country that belittled and mistreated them. The Treaty of Peace, Friendship, Limits, and Settlement between the United States of America and the Republic of Mexico—commonly known as the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo—was supposed to ensure respect of Chicanos’ property, language, and culture. But the Chicanos were quickly expropriated, pushed to urban fringes, in barrios and colonias, and forced to use the assimilative language of English. They were no longer Mexicans yet not really considered as Americans, so then embarked upon an existential and spiritual journey that led them to emphasize their indigenous roots and anteriority on their land. They cultivated the idea of a glorious past with mythical origins and an ennobled identity.

In the decades that followed the Mexican–American War, up to the 1960s, Chicanos lived like children from a divorced couple: they were moving freely from one country to the other and crossing the border both ways. They cultivated a form of cultural exceptionalism from a blend of Mexican folk traditions and the US way of life. But on US soil they remained victims of discrimination and racial, social, and geographical segregation. So they ended up having their own revolution. In the 1970s, they began a struggle for civil rights by creating a widespread political and artistic movement: the Chicano Movement. They practiced a militant, committed, protest form of art that naturally spread up and down the walls of big US cities, where murals flourished. This especially emerged in Mission District, San Francisco’s Latino neighborhood, and in San Diego’s Chicano Park, which has become a veritable open-air museum beneath the bridge that spans San Diego Bay.

Aude-Emilie Judaïque

Both San Diego’s Centro Cultural de la Raza and San Francisco’s Galeria de la Raza, opened in 1970 to promote the Chicano community’s works of art and defended its rights. Frida Kahlo and Diego Rivera were seen as role models for championing traditional Mexican art in the US. The duo therefore became the mother and father of a new generation of artists who drew inspiration from their lives and works to try to make Rivera’s dream of a sacred union come true. In their art, Chicano artists lay claim to a transborder and transnational culture and extol cultural hybridization speaking Spanglish—a language that mixes Spanish and English.

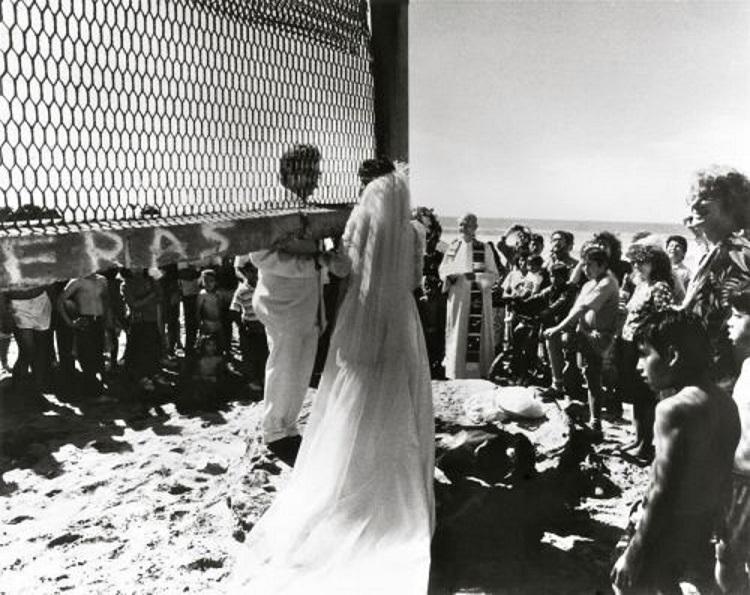

In this context of artistic and political emulation, the BAW/TAF (Border Art Workshop/Taller de Arte Fronterizo) group was founded in 1984. The group organized the first transborder and transdisciplinary collaborations between the twin cities of San Diego and Tijuana by bringing together artists, activists, journalists, and scholars from both sides of the US–Mexico border. These BAW/TAF “artivists” invented the expression “border art”: they constructed and deconstructed our representations of the border and played around with images we associate with it–sometimes as a wall, sometimes as a connection, as in this “border wedding”:

Emily Hicks & Guillermo Gómez-Peña, "Border Wedding", 1988

On March 11, 1988, Guillermo Gómez-Peña, a founding member and leading figure of BAW/TAF, married Emily Hicks, the artist who shared his life, both at work and home. The bride and groom exchanged vows on the San Diego–Tijuana beach, which the border splits in two. They also switched places: Gómez-Peña, a Mexican, stood on the US side while Hicks, an American, stood on the Mexican side. Both then symbolically moved forwards, stepping towards one another, putting a foot in one another’s country. This simultaneous movement and reciprocal border-crossing is vital to laying the grounds for a harmonious union.

“The border becomes a metaphor for a coming together. We met here and we have made the border our life. The wedding was the ultimate statement of our dedication.” (Guillermo Gómez-Peña in the Los Angeles Times)

So this photograph is of a true wedding, immortalized as an artistic and political act, and then incorporated into a series of performances in which the artists call borders into question by becoming the subjects of their art on the US–Mexican border. For this binational couple, who live and work both in the US and Mexico and brought up their children in both cultures and languages, border art is a way of life, of inhabiting the space in-between, of asserting a mixed-race and culture identity. This is because border art is basically a hybrid art. In this sense, it is a natural child of the Mexican people, whose national identity is based on the concept of racial mixing (mestizaje), a breeding ground of this “Amexican” identity that has developed in the US–Mexico borderlands.

Border art is the art of our time, an art that observes the world as it is todayglobalized and crossed by ever more people moving from places to places and in all directions. Border art asserts that any border can be crossed: it encourages -mixing-styles, the emergence hybrid practices, and the promotion of borders as intersections, places of encounters, dialogue, and exchanges between two people, two countries, or simply two artistic expressions, as Rivera said. This is because borders—locations where everything crosses paths and converges—are where newness and creativity sprout.

So a border is also an ecosystem, full of life and energy. It is a matrix, a space for freedom and inventiveness, a place where one can dream, take refuge, or escape—if only in one’s imagination. All things considered, would Frida Kahlo have painted had she not had that road accident that confined her to bed for months? Did those four walls that enclosed her not help her get up? Were her scars not liberating? In the same way, border art is cathartic: it helps overcome difficulties, soothe pain, and learn resilience.

From footholds in modern Mexican art to contemporary border art and through the Chicano Movement, artistic practice at the US–Mexico border has grown considerably over the past century. Year in, year out, depending on whether immigration policies loosen or tighten up, transborder artists highlight the full complexity of borders and play around with a paradox: we need limits, but we also need to be able to rise above them. A border is like a marriage of convenience that can turn into a passion if the two parties make an effort to accept their differences and recognize how much they depend on one another. This gives birth to happy children in this interposed world—children who are no longer torn between narrow identities.

Therein lies the other lesson from History: the one the South tells the North, the one Mexico tells the US. It is the story of a multicultural country where Mother Earth and Father Sky produced rainbow children, fruits of the Tree of Liberty; an Art History that is not told enough; a story of artists split by a the border and sometimes filled with the border; a tale of a front line that is also a lifeline, where people play around with death but play it down too. It is no coincidence that border art was born in Mexico. Neither is it a coincidence that it is flourishing today as fast as countries are walling themselves up. It is high time to promote and recognize this art of compromise, of balancing forces, of mutual respect. And it is just as urgent to preserve existing art and safeguard the works of trailblazers.

For over twenty years, Diego Rivera’s Pan American Unity remained stored away in crates. Only in 1961 did it find a final home in City College of San Francisco (CCSF). Since June 2021, when CCSF closed for building work, the mural has been loaned to the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art (SF MoMA), for a period of three years, on display in an area of the museum anyone can enter for free so that everyone can dive in and out of this pan-American dream as they like. Get yourself over there to see it if you can, and make sure not to miss the retrospective devoted to Diego Rivera, till January 2023!

Aude-Emilie Judaïque is a producer of documentaries on international migration and borders, and Villa Albertine resident in San Francisco from February to March 2022 for her roving exhibition project, Exploring borders, that she is co-curating with Anne-Laure Amilhat-Szary (political geographer) and which is produced by Chloé Jarry (Lucid Realities).

Interview with:

William Maynez, steward and historian of Diego Rivera’s Pan American Unity mural at City College of San Francisco (CCSF) for more than twenty-five years, now serving on the SFMOMA–CCSF team coordinating the loan of the masterpiece for the museum’s current exhibition, Diego Rivera’s America (July 16, 2022–January 2, 2023)

Michael Dear, Professor Emeritus in the College of Environmental Design at UC Berkeley, author of Why Walls Won’t Work: Repairing the US–Mexico Divide (Oxford University Press, 2015) and co-curator with Ronald Rael (author of Borderwall as Architecture: A Manifesto for the US–Mexico Boundary) of Califas: Art of the US–Mexico Borderlands, an exhibition showcased in 2018 at the Richmond Art Center.