Colors of the Mississippi

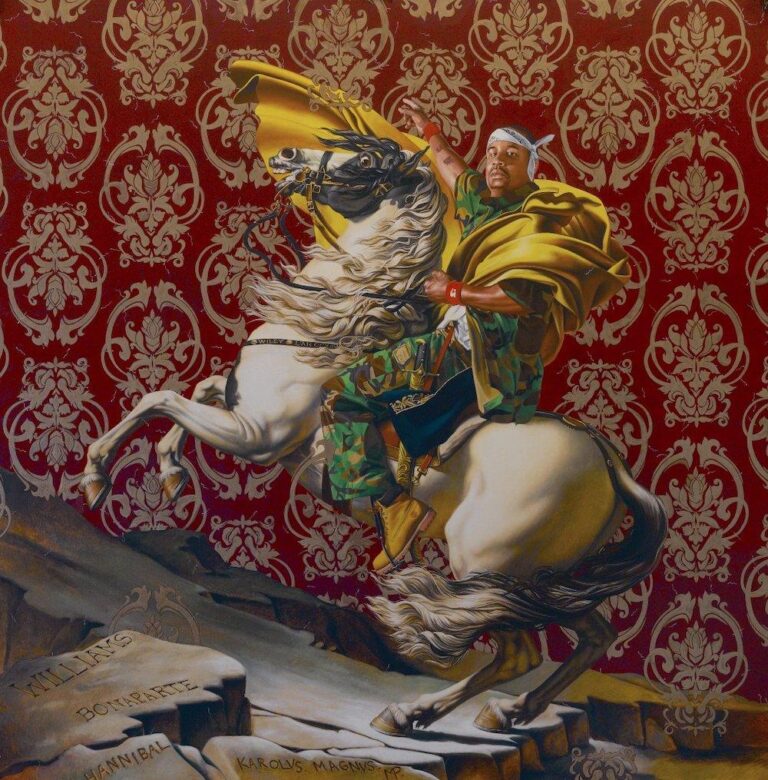

Delta du Mississippi ©Nicolas Floc'h / ADAGP 2022

By Nicolas Floc'h

“Rivers condense the history of peoples and civilizations. They embody the links we have with our environment and are directly connected to the ocean.” Through his shots capturing the color of the water, photographer and Villa Albertine resident Nicolas Floc’h gets us to sail through the Mississippi River and documents the impact of humans on their environment. Let’s dive into the heart of one of the richest and most fascinating Deltas of the planet!

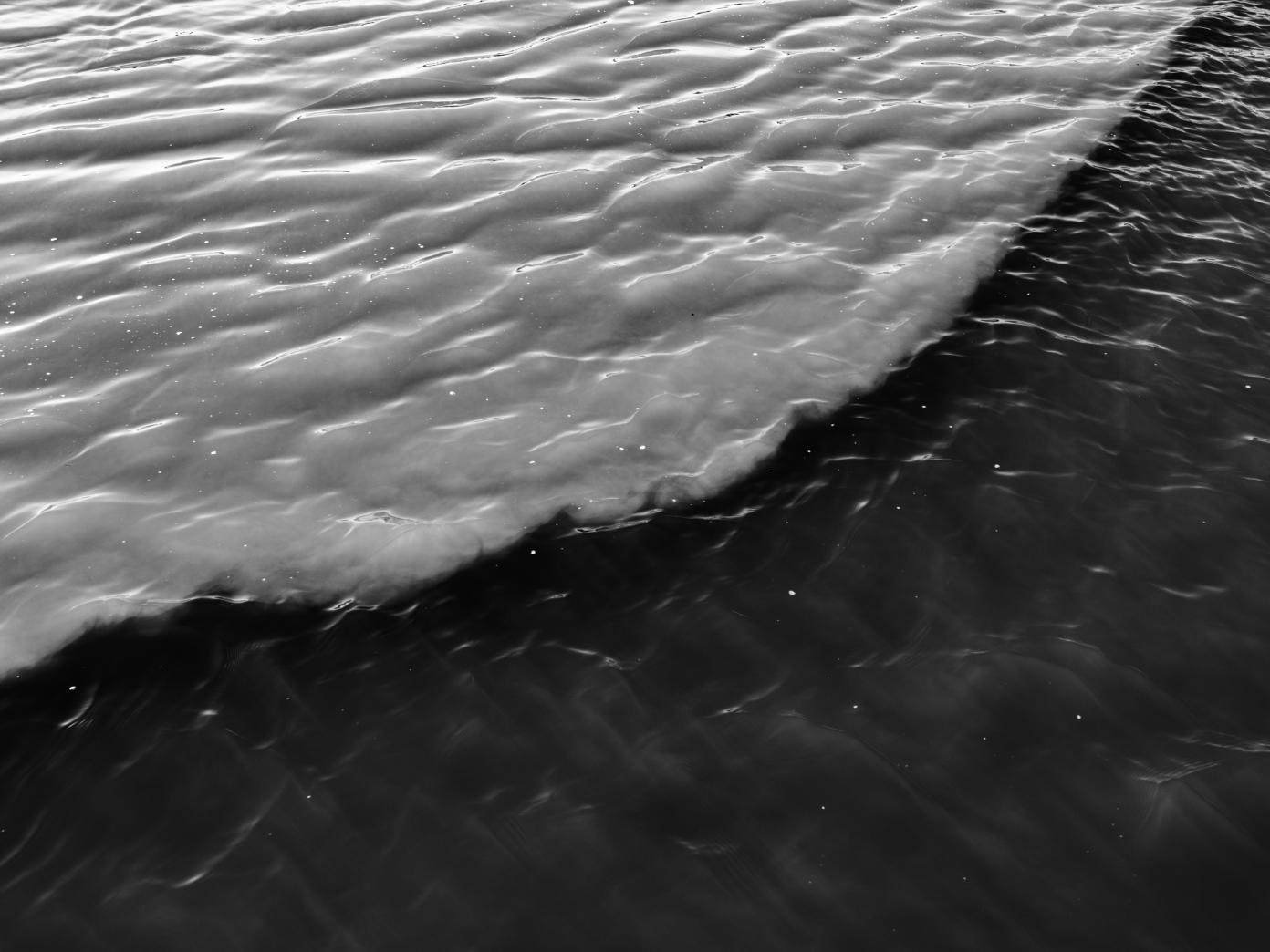

Sediments, dissolved organic & inorganic matter – The Mississippi Delta, between Empire and Delta ©Nicolas Floc'h / ADAGP 2022

Sediments, dissolved organic & inorganic matter – The Mississippi Delta, between Empire and Delta ©Nicolas Floc'h / ADAGP 2022

Sediments, dissolved organic & inorganic matter – The Mississippi Delta, between Empire and Delta ©Nicolas Floc'h / ADAGP 2022

Sediments, dissolved organic & inorganic matter – The Mississippi Delta ©Nicolas Floc'h / ADAGP 2022

Sediments, dissolved organic & inorganic matter – The Mississippi Delta ©Nicolas Floc'h / ADAGP 2022

Sediments, dissolved organic & inorganic matter – The Mississippi Delta ©Nicolas Floc'h / ADAGP 2022

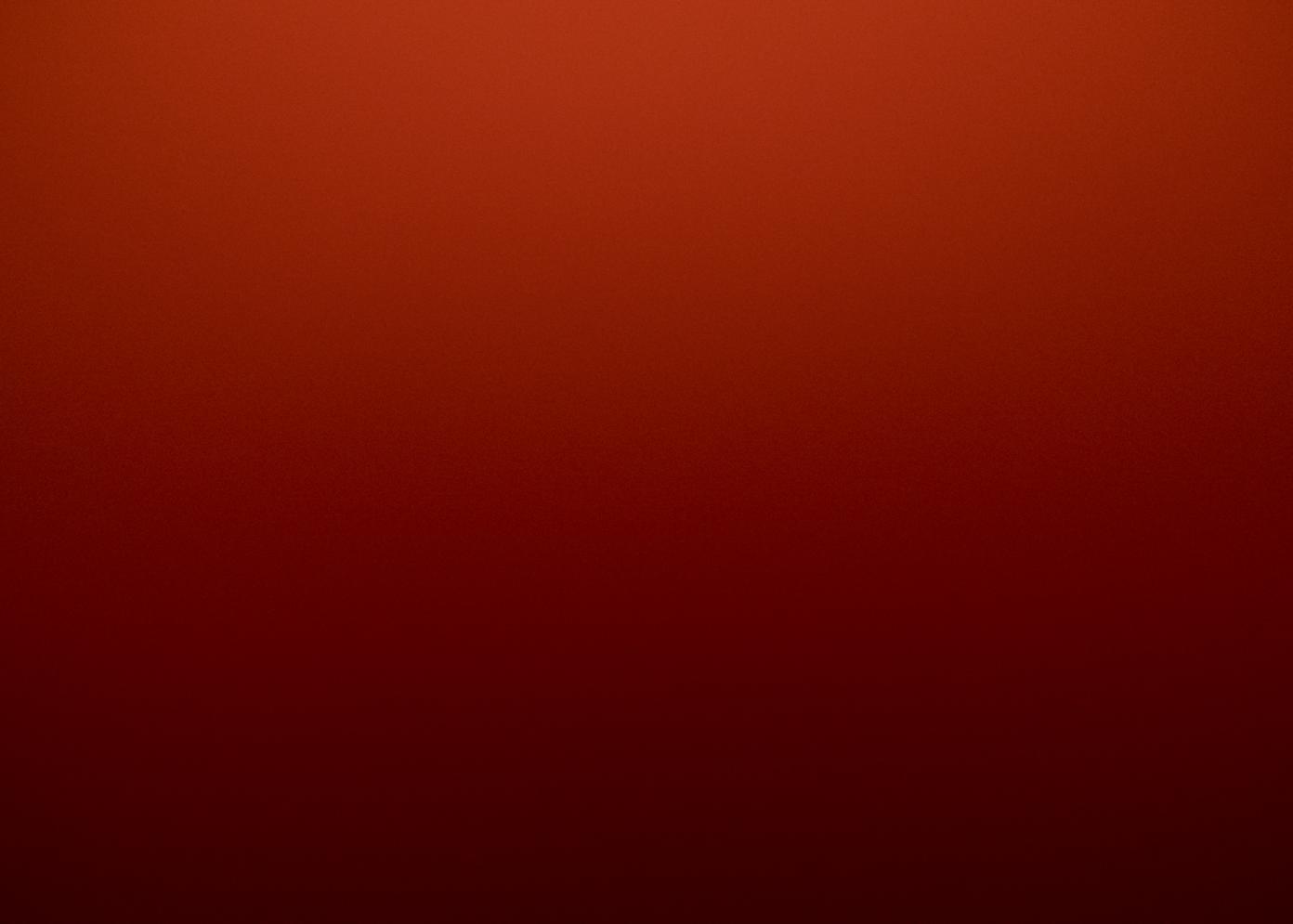

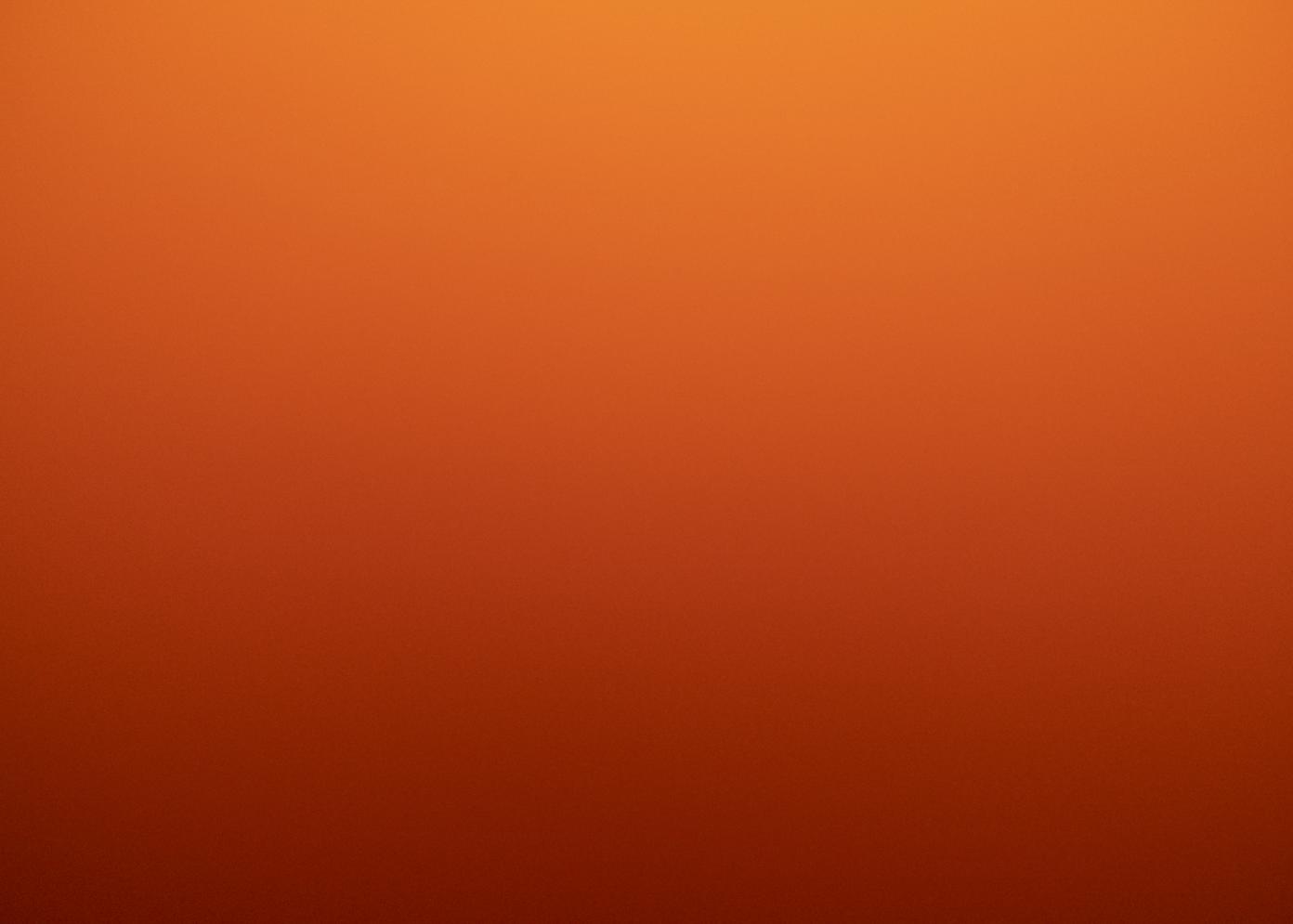

Phytoplankton – The Mississippi Delta, entry into the Gulf of Mexico ©Nicolas Floc'h / ADAGP 2022

Phytoplankton – The Mississippi Delta, entry into the Gulf of Mexico ©Nicolas Floc'h / ADAGP 2022

Phytoplankton – The Mississippi Delta, entry into the Gulf of Mexico ©Nicolas Floc'h / ADAGP 2022

Phytoplankton – The Mississippi Delta, Gulf of Mexico ©Nicolas Floc'h/ ADAGP 2022

Phytoplankton – The Mississippi Delta, Gulf of Mexico ©Nicolas Floc'h / ADAGP 2022

Phytoplankton – The Mississippi Delta, Gulf of Mexico ©Nicolas Floc'h / ADAGP 2022

My study of submarine landscapes and habitats, along with their role in balancing ecosystems, brought me to document the most common landscape, the “water column stratification” space–the water itself. The ocean represents the main part of this vital substance; it is the engine of living things, of the climate, and is in constant interaction with the earth, ice, and the atmosphere. As a matter of fact, the water cycle involves constant evaporation on the surface of the seas and continents. This atmospheric water irrigates the land and builds up the ice. While it flows, it gets enriched with mineral salts, sediments, and organic matter, and then permeates the earth’s crust and fertilizes the waters of rivers and oceans. These streams, real hydrographic webs that run through territories, bring life and support human life, even as we have more and more of an impact on the environment.

The Fleuves-Océan (Rivers-Ocean) project aims to expand the reading we have of the ocean, but from the earth as a complementary and nourishing space, revealing the symbiotic relationship between our planet and the water that covers it. The color of the water, the geomorphology of landscapes, and anthropization are elements that allow us to analyze our environment.

Fleuves-Océan seeks to explore these flows—from their sources to their mouths, from their watersheds to their drainage basins—and to follow the water’s path across territories into the very depths the Earth.

The Mississippi River, like a tree standing at the center of the United States, drains a significant portion of the territory’s land. To the north, the source is a glacial lake in Minnesota that shows us the origins of the flow that runs to Louisiana to the south, and to the waters of the Gulf of Mexico. The lake must be supplemented geographically by the sources, the flows, and the territories of the main tributaries, taking us from the Rocky Mountains to the Appalachians. The color of the water at the river mouth carries soil coming from the north, east, and west. It is diluted in the blue of the ocean’s waters, fertilizing them and transforming the environment through anthropogenic emissions, leading to the eutrophication of coastal waters.

For the first part of my residence with Villa Albertine, I spent a few weeks sailing around the Mississippi Delta. My goal was to work on the river’s delta, and mostly on the color of the water from the subaquatic space, but also to wander the bayous–the old beds of the Mississippi. My guide, Richie Blink, and I sailed more than 600 miles through the Delta, the Gulf of Mexico, the bayous and the swamps. The area we explored is between Baton Rouge, the Mississippi Delta from Empire, Venice, the bayous, the Atchafalaya Delta, which drains 30% of the river’s flow, and the Gulf of Mexico.

The main grid between the river and the ocean is a transect with vertical profiles extending over 60 miles and using about 40 points, spaced out by a few miles each. Every photographic profile may be likened to a core sampling in the water column stratification, and the color provides us with some information as to the living things, organic material, and minerals that may be found there. All these photographs—assembled in the form of lines, columns, or grids and respecting the order of the shots—represent cross-sections in the water masses. We go from the sediments and the dissolved organic matter of the river (red, orange, and yellow) to the green phytoplankton, before returning to the not so rich blue offshore areas.

Rivers condense the history of peoples and civilizations. They embody the links we have with our environment and are directly connected to the ocean. The vital aspect of rivers has brought us to inhabit their banks, but they, along with the atmosphere have also become one of the main vehicles of the spread of polluting substances and our excesses, as well as symbols of our inverted relationship with the world, in which the vital flow makes our future more uncertain with every day that passes.

Villa Albertine / Fondation Camargo.

In partnership with Artconnexion, Lille / Fondation Daniel, and Nina Carasso.

©Nicolas Floc’h / ADAGP 2022