(LA)HORDE: “Dance is that sensitive political space”

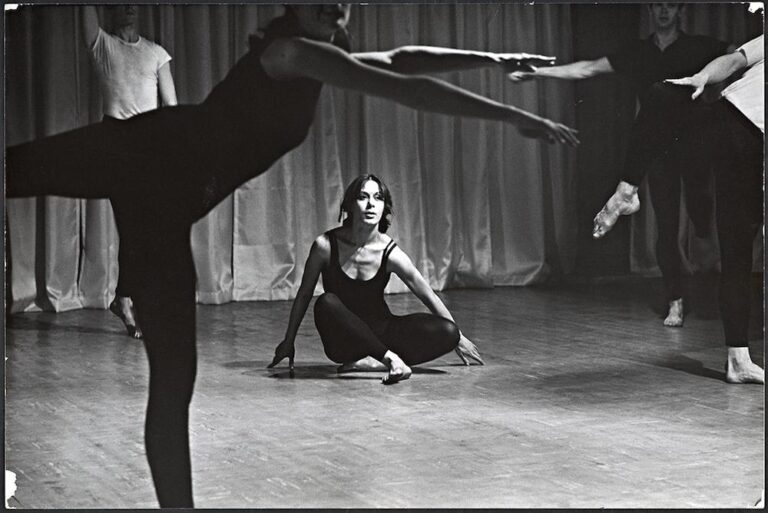

© Boris Camaca - DA Alice Gavin

By Raphaël Bourgois

(LA)HORDE speaks with a single voice. This collective body created by the artists Marine Brutti, Jonathan Debrouwer, and Arthur Harel actually goes beyond the three individuals; at the heart of their practice, dance becomes a sensitive and political place where questions related to gender, racism, sexuality, and power are addressed. From New York to Los Angeles, (LA)HORDE sought out what makes people tick.

Tell us about Los Angeles–what did you come here to find?

We’re familiar with LA, because we’ve worked here before. It’s an amazing city that reminds us, in a way, of Marseille, where we’ve been living for several years. Mostly because of the light, which is incredible in LA, the proximity of the sea, and a certain lifestyle that’s both urban and very close to nature. Also, violence is never far away and there’s a disparity of living conditions, with great inequalities that are flagrant and upsetting… We also feel at home here because there’s a large artistic community, even though dance isn’t very developed as yet. We know people in the field who do some amazing work, with whom we exchange a lot, such as Dimitri Chamblas, the former Director of the CalArts Dance School, or LA Dance Project’s Benjamin Millepied, and we’ve met a whole network of self-taught dancers through the so-called “post-internet” dances that emerged from hip-hop, krump, etc. There’s an incredibly rich field for dance, and it’s ripe for networking and expansion.

We came here four years ago to work with jumpstyle dancers as a follow-up to our first big production, To Da Bone (2017), which featured talented self-taught dancers who had used the Internet to learn to dance and meet each other; it also explored the reasons that compelled them to move. Jumpstyle had become a social phenomenon in Europe–one that we saw as a form of emancipation for young heteronormative cis males, whose choice of dance represented a deviation from the physical activities traditionally associated with boys. In both New York City and Los Angeles, we discovered that jumpstyle was empowering and bringing diverse communities together as it followed the usual path from the privacy of the bedroom to the public sphere, through the encounter with other dancers. It was appropriated by minorities: a young trans person, Latinx, immigrants… What was fascinating when we staged To Da Bone in North America with our European dancers was to see how a shared artistic principle led to connections being made, bridges being built, and friendships being formed between very different communities. Our work centers on this.

Five years have passed since you came here with To Da Bone. In the meantime, some very different practices have emerged, in terms of online dance, but there was also a long period when the pandemic prevented people from getting together. What was the situation when you arrived in the US?

We landed in New York City after 18 months of COVID and we immediately sensed a significant social tension. It’s a city of services (systematically provided by racialized workers), and the lack of personnel due to the pandemic created a rather heavy atmosphere. Although Los Angeles also suffered from the crisis, and the number of homeless had increased since our first visit, we nonetheless sensed a certain gentleness that we didn’t feel in New York City.

But what we find really stimulating in the United States is that people are sufficiently informed about issues of gender, sexuality, and racism for these conversations to take place, whereas they are still a source of far greater tension in France. On the other hand, access to culture, art, and health is much easier in France. So we felt hybridized when we came back to France, as if we were adrift between two countries that have so much in common. In any case, in the US we felt we were on the same wavelength on all those topics, and that was a good feeling.

What do you mean by the term “post-internet dance”? How do you see the evolution of dance with the emergence of new social networks such as TikTok?

To answer your question, I’ll make a detour via our dance collective. When we first met, we were young artists, friends who wanted to make a place for ourselves. After our first production, we realized we would need a collective signature name, and that’s how (LA)HORDE came into being. We chose it because it’s so inclusive: it can encompass just the three of us, or a hundred people. We are a very tight group: we share videos, read the same things, visit the same exhibitions… What we call “post-internet” is the new contemporary art movement that emerged with the advent of Internet 2.0, circa 2005–07. Artists from all over the world were suddenly able to communicate aesthetically, and we had endless conversations about that possibility. So “post-internet dance” refers to a system of artistic thought and practices that we use in the studio with the dancers, inspired by the dance forms that have emerged online and given rise to their own culture and history. That said, the viral movements that are currently emerging on TikTok represent a new stage, characterized by their viral nature, their ephemerality, and the fact that they can bring hundreds of thousands of people together. So there is a distinction between viral dances and post-internet dances which can take place in real life. Jumpstyle dancers, for example, use the Internet as a tool for empowerment: they can get in touch, exchange, make progress, and build a shared culture. But they always end up meeting in person at events they take part in together.

As your name suggests, you explore the link between individual, community, and collective–tensions exacerbated by the Internet. Could you tell us more about the political commitment and protest at the heart of your work? How can dance also be a political tool for bringing people together?

As a collective, we are interested in other people. To quote dancer and choreographer Pina Bausch, “I’m not interested in how people move, but in what moves them.” That idea is a recurring theme in our work. All three of us need to be touched by an emotion, an expression of mastery, something beautiful, something spectacular. We are fascinated by the inexplicable because to us it means something just happened, but I must admit that we also really enjoy the phase of conceptualization and exchange with performers, when we explore the reasons behind their movements.

Dance today is a universal language, without words, unstructured by a text. Its ability to unite is a source of power for communities that can no longer express themselves or do not, strictly speaking, have a place in society. For us, dance is that intensely sensitive political space. We became aware of that when we looked into the origins of jumpstyle as a means of political expression, and discovered that it was inspired by traditional dances in the former Soviet republic of Georgia. So we went there, and realized that Georgian dances are now linked to an extremely influential LGBT-techno music movement, and that they were also a means of resistance to the Russian invasion in 2008. The use of terms such as “traditional dance” or “concert” to designate certain shows is actually a means of avoiding censorship. They continued to innovate within that “tradition,” with a whole underground techno network that meets in the Bassiani nightclub, within the Dinamo Arena, in Tbilisi, where young people get together to discuss gender and social issues, sexuality, power, politics… against a background of techno and traditional dances.

Bassiani represents everything we want to touch on–it’s a blend of political, organic, and sensory elements, and it inspired us with a new creation, Marry Me in Bassiani. But such stories are never entirely our own; we do not work alone. We find our answers through sharing, experimentation, and in-between paths, by playing with a form of drama between fiction and reality. The political and aesthetic aspects of violence have played a big part in our work over the last ten years, and our inclination today is towards what we intend to be a powerful material, physically committed in gestural terms, but one that also strives for light and hope, because it is difficult to take a “neo no-future” stance at the present time. The aesthetics of violence will still be part of our work, but the nature of the violence may change; we’re still young, after all.

So you really feel the need to create, to include a form of optimism, to say that there’s light at the end of the tunnel. Does that mean you think that the no-future nihilism of punk is no longer tenable today?

In our view, being punk today means finding the light. Since the beginning of (LA)HORDE, in 2011, our aesthetic of violence has always incorporated a form of jubilation, ritual, and elevation that comes from the fact of being a group. Like it or not, when the jumpstyle dancers jump on the spot, in silence, for the first ten minutes of To Da Bone, that repetition contains a violence that creates a unity, leading the audience to hope that something is going to happen.

The COVID lockdown put a stop to our latest production, Room With a View, one that we had mounted with the dancers of the Ballet national de Marseille, so we were deprived of dance for a year and a half. During the process of creating that show, composer and musician Rone shone a new light on our work. He helped us understand that the Ballet national de Marseille is a specific, ephemeral community (comprising some fifteen nationalities this season), and that the choreographic piece resulting from our collaboration had to express something of the world we live in. Since Room With a View, we have been looking for a shining path and, although it may not be apparent to everybody, that kind of light is synonymous with violence in our mind.

You’re multimodal artists with an interest in contemporary art and scenic practice, music, video… You’ve mentioned Rone and electronic music, which is very important in your work. Tell us about your use of video. How much room do you give to it?

It’s quite natural for us to use video, which provides us with a different kind of scenic practice. It’s a means of getting closer to the performers and using a more direct writing style than we would for theater. The different media do not cancel each other out; they allow for an accumulation of works and perspectives that enables the spectator to discern a choreographic piece through a variety of filters. As we are also great movie fans, there are always elements of cinema in our choreographic work and on the stage. For us, the use of video is absolutely not a business calculation; it’s a narrative mode that allows us to tackle the issues we’re interested in. We can use video to make a documentary or a contemporary artwork, a music video, or to create a record of one of our performances (as we did for The Master’s Tool at the 2017 Nuit Blanche in Paris, which combined sequences suggesting a filmed installation with others captured on a cell phones).

You collaborated with US filmmaker, producer, and screenwriter Spike Jonze on the “Ghost” video. How did that come about?

That was our American adventure—our lockdown folly! We had filmed a music video for Room With a View with the Ballet national de Marseille, at the end of which the dancers form a monster and fly away. Little did we know that the monster would turn into a virus that would stop the show. Anyway, the video went viral. One day, we received an email from US producer David Zander of MJZ, who insisted on setting up a meeting. We did a little research and found out that he worked with people we admire, including Spike Jonze, Harmony Korine, and Chris Cunningham. He put us in touch with Spike, and we spoke via Zoom. We couldn’t believe it! After that, Spike wrote a short scenario for us, that we filmed at the Musée des Beaux-Arts in Marseille; from then on, he became our sponsor at MJZ.

To go back to the link between dance and partying—as we have just lived through two years without being able to party together—what do you think is lost when parties are no longer possible, and what do you hope their return will bring?

Parties are places of transgression, crucial heterotopias, especially in the kind of times we’re living through today. Such spaces are particularly dear to us, because we first met in that kind of safe place (LGBT parties in Paris, such as Flash Cocotte, and the Possession nights). For us, partying encompasses everything from birthday parties to techno clubs. Although things are currently settling down in France, the “other” is still presented as a threat, and parties are seen as being synonymous with violence. We think the opposite is true: they are places of protection against violence, allowing for a different kind of relationship with others, enabling the generations to mingle. When we were in Tbilisi, we were touched to see the role techno still plays in places of contestation and rebellion. This is proof, once again, that music, and art in general, can make things happen. We have to do all we can to ensure that parties don’t die out, and that they continue to have a place in our society, because they are political spaces.

Marine Brutti, Jonathan Debrouwer, and Arthur Harel, who started the collective (LA)HORDE in 2013, are at the head of the National Ballet of Marseille. As multimodal artists, they create contemporary dance shows, both on-stage and filmed; dance informs their choreographies, films, performances, and installations. They have collaborated with some big names in American cinema and French music. They stayed in New York City and Los Angeles for their Villa Albertine residency, co-curated with Art Explora. You may find their productions and video clips here.

Subscribe to the Villa Albertine Magazine newsletter