Chicago: An Impossible Transformation?

Courtesy of GRAU

By GRAU

Everything in Chicago is subject to the grid, structuring—which is not to say constraining—the relationships between the inhabitants and their environment. The GRAU Collective—made up of architects and urbanists Susanne Eliasson and Anthony Jammes—went to the main metropolis in the Midwest in order to understand how the physical space of the city may be redesigned.

Miles and meters

Courtesy of GRAU

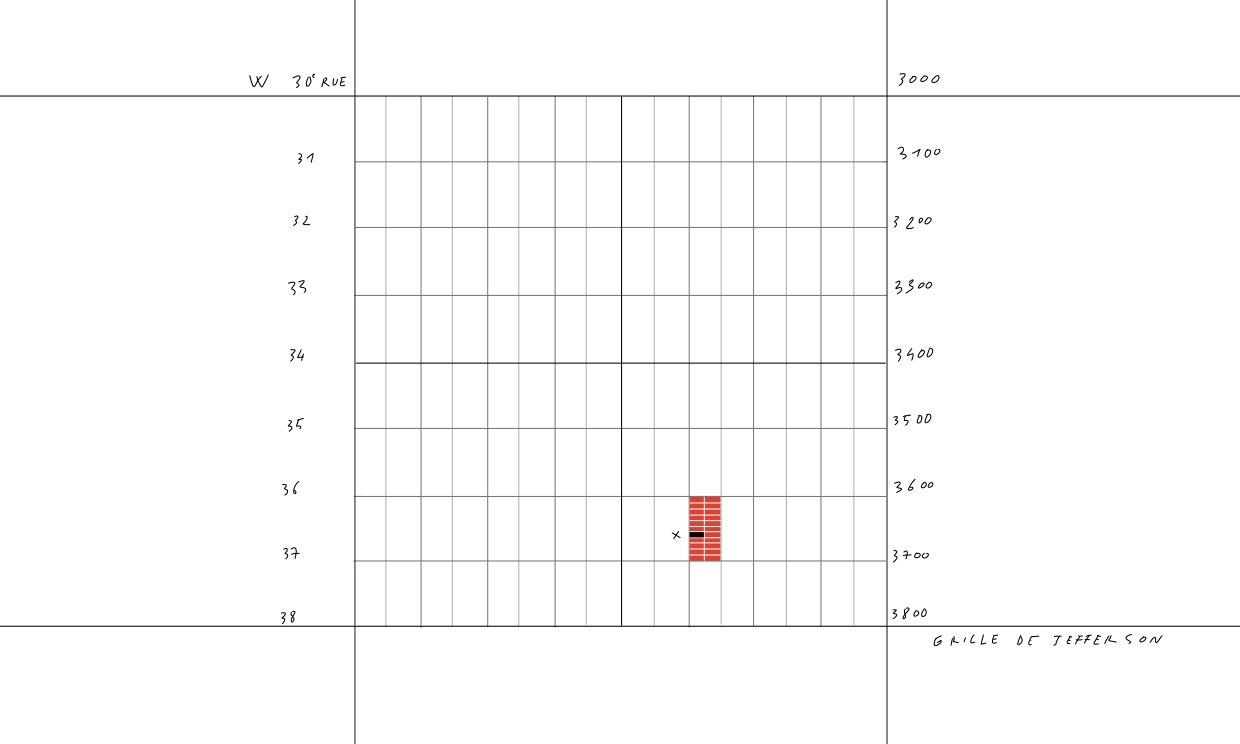

The urban structure of Chicago is founded on the basic square of Thomas Jefferson’s grid, which was adopted in 1785 to survey the land as the US expanded westward.

Each section of the grid is one square mile. The city’s large avenues run alongside these superblocks, starting from point zero, at the downtown intersection of State and Madison streets, in the Loop. The squares were then divided into eight and sixteen to form the basic unit of Chicago’s urban grid—a rectangular 330×660-foot block with a middle alley leading to every parcel on the block.

Each block encompasses 100 street numbers, so there are 800 street numbers per mile, and 1,000 street numbers equal 1.25 mile. Every address is prefixed by its direction in relation to point zero—N, S, W, E; once you have grasped that, an address itself tells you its distance and bearing from point zero. 2000 N State Street is 2.5 miles north; 800 W Randolph Street is 1 mile west.

Whether you use the metric or imperial system, the grid is a universal unit of measurement that enables strangers to the city to find their way easily.

Organic

Courtesy of GRAU

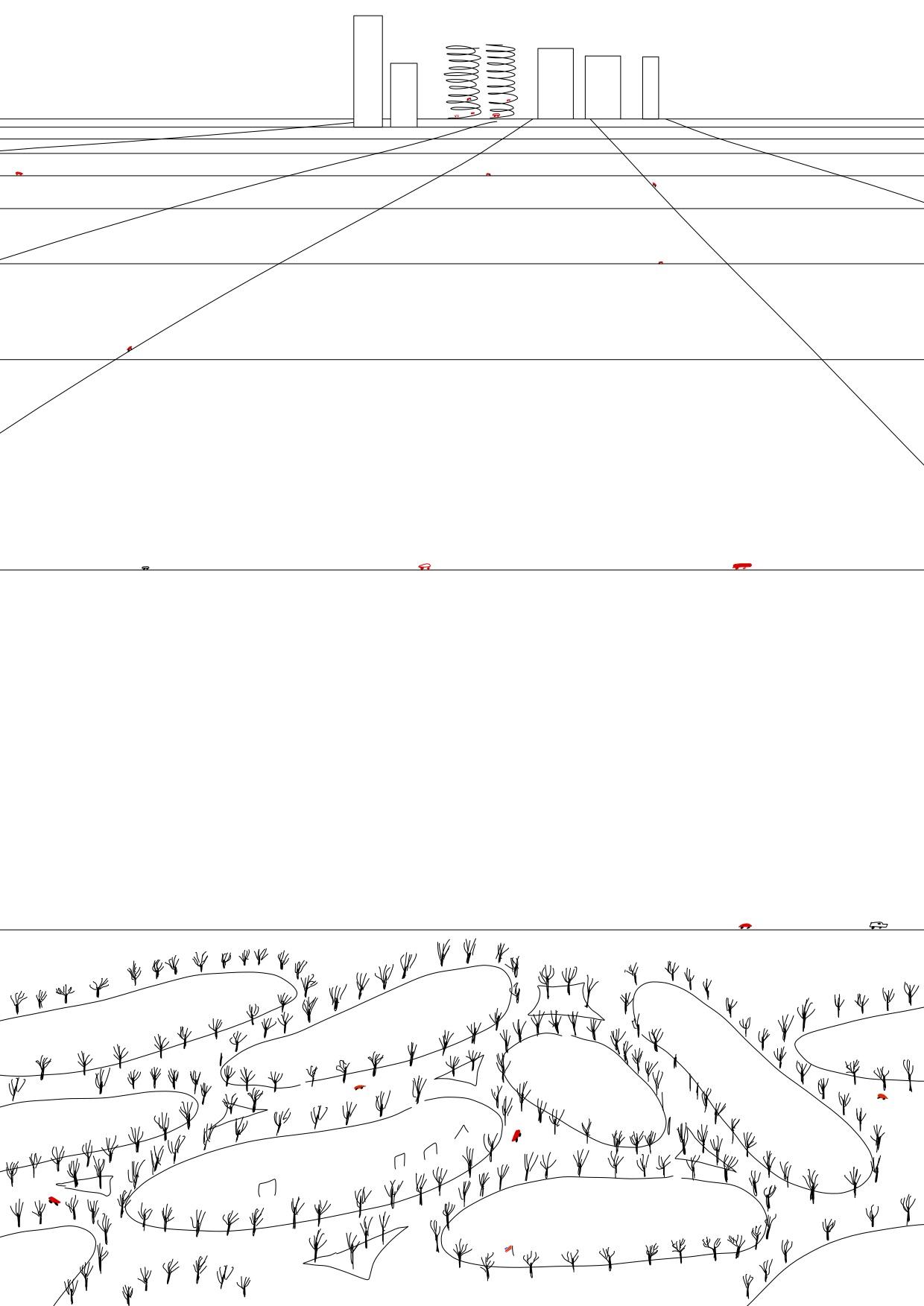

A Sunday morning in February. It’s 14°F outside, Covid is still in the air, and the Super Bowl is on tonight. There’s nobody around, and we soon feel the need to go and warm up in a shopping mall. We’re not the only ones, and we do what everyone else does: drink coffee on the couches provided in this indoor public space before hitting the road again.

A little to the north, along the Chicago River, are the two round towers of Marina City, designed by Bertrand Goldberg in 1964. With 900 apartments above 19 levels of parking space, it’s one of the city’s most densely populated complexes. Marina City is famous for its corncob-shaped towers and the green Pontiac that plummeted from its circular ramp in the movie The Hunter (1980). The ramp starts off innocently enough on the first floor, with cars parked all around it and between the two towers.

Marina City is also home to the House of Blues and the Smith & Wollensky Steakhouse, with its green awning that reaches out to pluck customers from the sidewalk of State Street. Each apartment in the towers opens onto a circular balcony with a super-high metal guardrail and a parasol-style roof that create a cozy outdoor room.

Ten miles to the west of Marina City is the village of Riverside, designed a century earlier by Frederick Law Olmsted and Calvert Vaux. Riverside was the first planned suburban community in the vicinity of Chicago. It has perfectly curving roads, and each intersection enjoys a triangular view. Although it is contained within two Jefferson squares, there are no straight lines; as you drive through the neighborhood, your hand is always at a slight angle on the steering wheel.

Marina City and Riverside are two extreme—but not completely opposing—examples of what can also be found in the grid. Each architect broke free of the grid, playing with it in his own way: Goldberg added urban density while rejecting the traditional American corner; Olmsted recreated fluidity within this typically American unit of measurement. Riverside and Marina City, two organic forms set up at the riverside, both offer a romantic vision of what can be done with the Cartesian grid.

Original Monopoly

Courtesy of GRAU

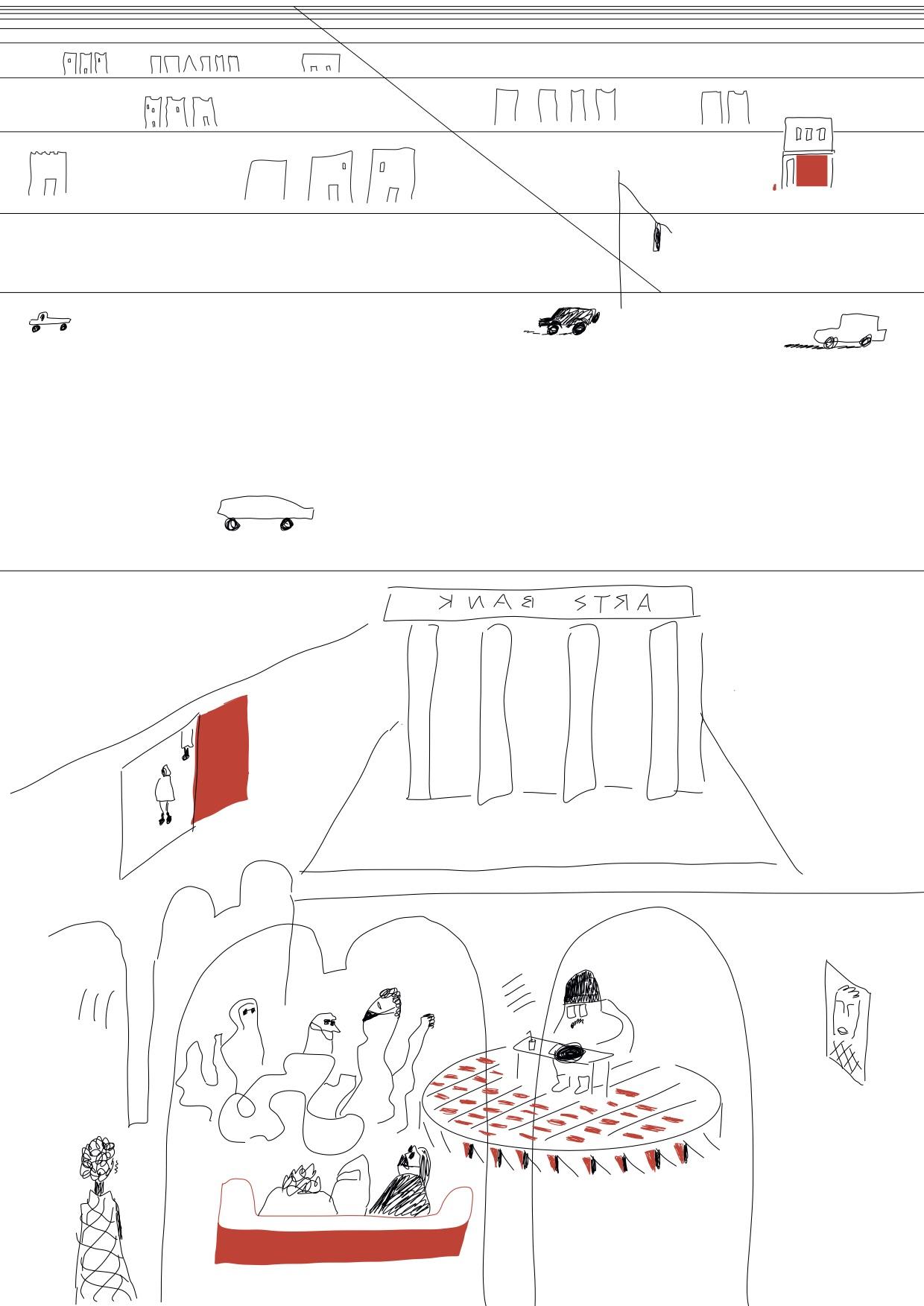

From the outside, Stony Island Arts Bank is hardly welcoming, with a façade featuring four large gray columns, thicker than the trunk of any hundred-year-old tree, and windows with drawn blinds. A little notice informs us that the entrance is the red door at the side of the building.

Inside, it’s a different story. The safe in the basement is empty, but the bank now houses new treasures that are currently being inventoried and digitized: book and magazine collection from the Johnson Publishing Company; glass slides from the University of Chicago and the Art Institute; the vinyl collection of Frankie Knuckles, the “godfather of house music”; and the Edward J. Williams collection of some 4,000 objects and statues representing stereotypical, racist images of the Black population (the very purpose of the collection was to take such offensive objects out of circulation).

Stony Island Arts Bank, a former bank built in 1923, is now a place that preserves the memory of Black culture in the United States, a building that contains a whole heritage. It is also a venue for temporary exhibitions and events.

The building stands out like a UFO in the urban Chicago landscape, on an avenue as wide as the Champs-Elysées in Paris. But Stony Island Arts Bank is a project with solid backing: it is managed by the Rebuild Foundation, the brainchild of Chicago-born artist Theaster Gates, who is working to transform the southern Chicago neighborhoods through cultural development and has mounted several projects in South Shore in recent years, including the Dorchester Projects, a series of houses that the artist bought up and converted into cultural spaces; Kenwood Gardens, where 13 abandoned lots have been turned into a community garden; and the Dorchester Art and Housing Collaborative, which provides social housing for locals and artists.

Chicago’s social geography was created by property and financial speculation from the private sector, which spent decades playing Monopoly with the city. The Rebuild Foundation and other local players are now playing the old version of Monopoly, The Landlord’s Game, and buying up land to gradually restore the community value of the neighborhood.

Behind the scenes

Courtesy of GRAU

During our first days in the city, the alleys were not really on our radar. Although there are alleys wherever the grid is present, from the Loop to the most outlying residential neighborhoods, they are less visible than the other streets—which is precisely what makes them interesting.

Mayors the world over are obsessed with the idea of a lovely and pleasant city. Chicago found its own solution from the start, by creating alleys. There are no trash cans or garages on the streets—a common problem in Europe—because they have been relegated to the alleys. These alleys are used by refuse collectors picking up garbage and by residents unloading their shopping. Freed from aesthetic norms, the alleys feature the kind of hodge-podge of fences and garage doors characteristic of many of our own city outskirts.

The alleys provide a welcome break from the practical but rather sterile layout of Chicago’s residential streets, lined with mile after mile of porched houses that are extremely similar. In recent years, in the more desirable neighborhoods, alleys have naturally become places of speculation for homeowners in need of more space, who convert their garages into a student apartment, a home office, or even a business—to the displeasure of certain councilors, who don’t understand the desire to densify the alleys when the city is full of vacant lots in neighborhoods that need revitalizing. And we understand their confusion.

So much more than places for real-estate speculation, alleys are interesting for their spatiality: their limited size, far narrower than the streets, is conducive to conviviality. The junk that tends to accumulate there today would still be there tomorrow, but instead of being taken on trucks to the city’s dumps, it could be processed collectively, on the spot, in the micro-society of the alley.

A collective America

Courtesy of GRAU

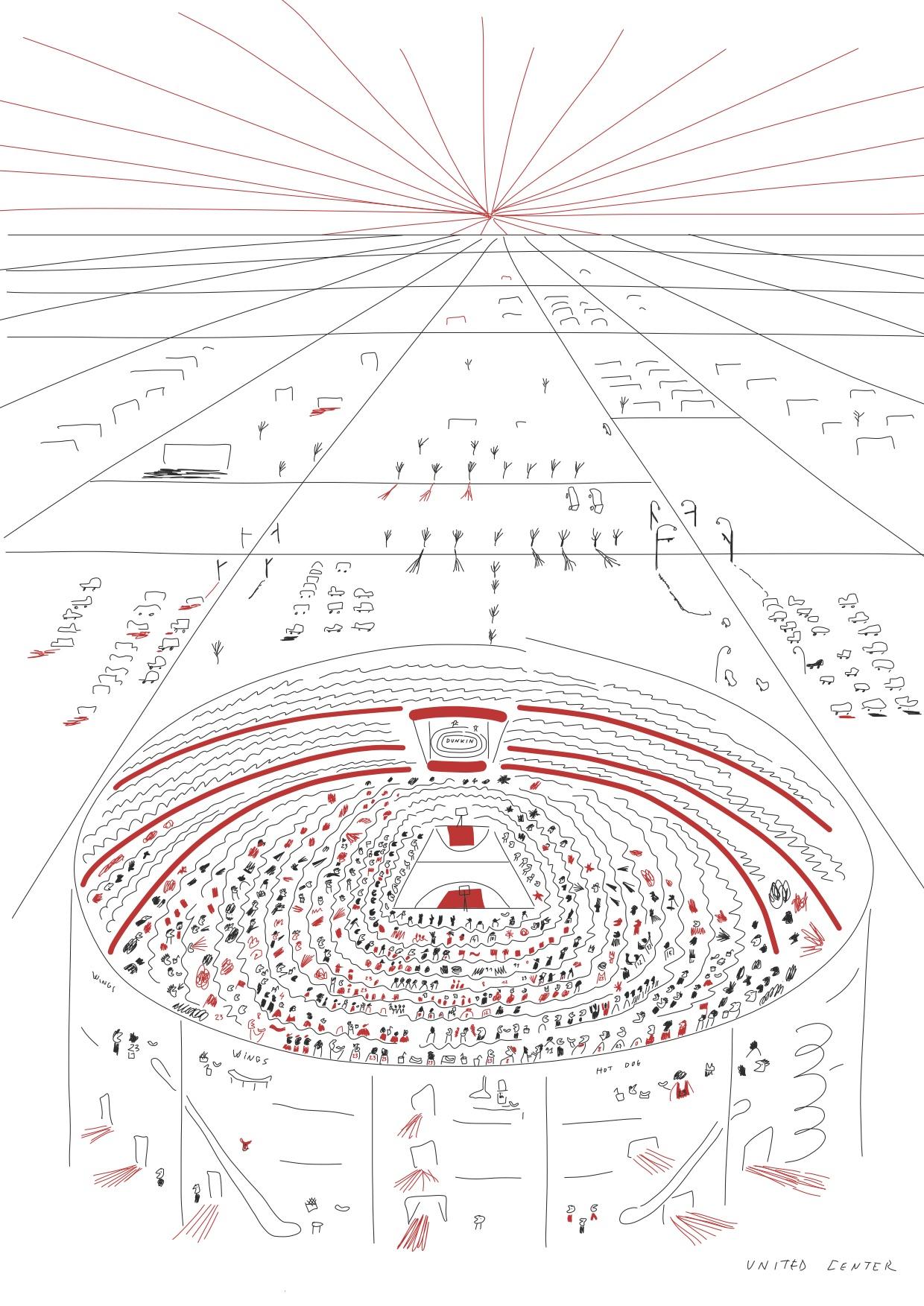

What will Chicago look like in 100 years’ time? It might seem like a strange question, but we shouldn’t forget that this is a city where anything is possible, from the rapid reconstruction and expansion in the wake of the Great Fire of 1871 that almost destroyed it, to the reversal of the Chicago River’s flow in 1900, to the new building techniques that resulted in the first skyscrapers that would soon shape cities the world over.

When you walk around the horizontal grid today—especially in the apparently under-occupied neighborhoods to the south and west—the challenges Chicago faces might seem overwhelming. But we should remember that these situations are not natural; they do not stem from the city’s organic transformation; rather, they’re the result of deliberate segregation and financial speculation. We should remember that, to remind ourselves that plenty of other paths are possible.

One afternoon, we received an email from Monica Chadha, the associate architect of the Civic Projects architecture practice, who showed us around the southern neighborhoods. Attached was a map showing all the vacant lots in Woodlawn, color-coding the city-owned lots and those that are private property.

We were surprised to see that the vast majority of vacant lots were actually public—yet another sign that there is indeed room for maneuvering. People may claim that the city hasn’t a single dollar to spend on transforming them, but let us not forget that Chicago is one of the richest cities in the world, in one of the richest countries in the world.

Chicago’s transformation requires considerable investment and commitment, but most of all it requires a clear vision of the type of city we want. What seems certain is that the Chicago of tomorrow will not be an endless extension of the grid, but a transformation of the existing one; the city’s future cohesion will be conditioned by the way the horizontal grid evolves in the coming years. Our vision for the future of Chicago can only come from within, from the people who live there every day… and plenty of visions have been shared with us during our discussions over the last two weeks.

What the grid clearly demonstrates is that nothing is impossible.

These texts are excerpts from the research on Chicago GRAU conducted. In the course of their residency, Susanne Eliasson and Anthony Jammes explored the relations between the inhabitants and the grid of the city. From there comes a series of points of view and ideas on the urban grid and its potential future—as many narratives that will feed the ongoing reflection on Chicago’s new urban planning: “We Will Chicago.”

Sign up for the Villa Albertine Magazine newsletter!