Art History in the Creation of Racial Identity

Kehinde Wiley, Napoleon Leading the Army over the Alps (2005), Brooklyn Museum

By Raphaël Bourgois

Strange as it may seem, Art History has been late in addressing the construction of racial identities. Yet the questions of what is seen, what is shown, the invention of “blackness” and “whiteness” are central, as Anne Lafont has brilliantly demonstrated. The historian navigates between the periods of the 18th and 19th century, and has shown how a look is built then on the Black bodies, in a manner consistent with the formation of an artistic canon. Canon which is today reappropriated and questioned by Black artists.

What perspective does art history bring to the subject of race?

To be perfectly honest, race has not always been a central theme in my research. After completing my thesis and finding employment, I wanted to explore new avenues and it was then that I became interested in the topic of Black representation. This research field was still in its nascent stages and, admittedly, I only grasped its fundamental importance several years into my iconography research on the construction of race and racism. My current area of study was formed out of two phases. The first was a positive research effort to compile an unprecedented corpus on the image of race and Black people within art history; the second, which helped me delve deeper into the subject, was an historical study of race based on visual and artistic objects. Another important milestone was the collective, multidisciplinary project that I became involved in fifteen years ago. Under the direction of Jean-Frédéric Schaub and Silvia Sebastiani at the School for Advanced Studies in the Social Sciences (EHESS), the project combined political, social, intellectual, and art history research. It was ironically very difficult to address these issues within my own discipline, even though art history has always been directly concerned with the visual, an aspect that is obviously core to how we experience race. We hardly need reminding that it is through sight that we define the familiar and the foreign; the similar and the different. And yet, I had to fight to prove the particular value of visual archives in the study of race history.

Your focus is on the 18th century, an era marked both by the Enlightenment and by the height of the slave trade. How can we resolve this apparent contradiction in the context of current debates around racism and universalism?

I don’t seek to resolve it! As an historian, I am aware of the great point of contention between 18th-century universalist philosophy and the reality of the slave trade at the time. I believe it is vital to acknowledge this flagrant contradiction before studying how it emerged and spread. For me, slavery helped sharpen the definition of citizenship and, by extension, the notion of republican universalism. Essentially, the citizen’s social and political status was developed deliberately in abstracto. Slavery was thus the crucial litmus test to prove the idea of citizenship as renewed by political revolutions around the Atlantic.

The paradox of universalist ambition relating to racial slavery is now unfathomable, but this was not always the case. When we look more closely at how the history unfolded, it becomes even more opaque than what both opponents and adherents of universalism claimed. That’s what makes the Enlightenment such a complex period. The way I see it, the experience of mass slavery, the trafficking of twelve million Africans, the colonial plantations, this cruelly pragmatic organization to dehumanize and exploit fellow human beings… All of it requires us to look at what citizenship actually meant in the 19th century. However, I find it unsurprising that racial slavery and universalist thought could coexist at that time. On the contrary, I would go as far as to say that the irrationality of the former somewhat stimulated the intellectual drive of the latter.

You wrote in your last book about a trend that emerged in the 18th century that you call “whiteness politics,” which also functions as an esthetic. How can art history help renew our understanding of this phenomenon?

When I presented the findings of my research that began in 2019, entitled L’Art et la Race : l’Africain (tout) contre l’œil des Lumières (Art and Race: the African up against (and under) the Enlightened Gaze, a certain historian, who shall remain unnamed, thought it appropriate to inform me that my work was utterly baseless. This person was flatly telling me that there wasn’t the necessary substance—the corpus of archives and works—to carry out the serious, important research of an historian on the subject; that the question of how race was constructed in the Enlightenment was basically worthless. Frankly, I was at first really offended, then just plain angry about what was objectively a bad faith assessment. In reality, as evidenced in my book, there are incredibly diverse representations and numerous iterations of Black figures in various areas of society, all of which has been immortalized in the visual archives. So, I took a quantitative approach, studying the bulk in order to demonstrate that these were not just a few one-off examples. Quite the opposite, in fact.

As for the fabrication of whiteness as a racial identity, this stemmed from the confrontation with blackness as embodied by the increased African presence in Europe over the 18th and 19th centuries. This up-close, amplified encounter with the Black other led, in turn, to the need to assert and perform whiteness, engendering various social practices like applying powders to the hair and face. I consider “the Enlightened Gaze,” as I call it, to be obsessed with Black subjects, Black bodies, and Africanness. And, to offer an indirect and much-belated response to that acquaintance of mine, this research was far from “baseless.” The quantity of subjects is so great that the question of race can be asked in every area, interrogating all the pieces that have existed in art history since the earliest days of the field. It is not an offshoot of the discipline; it is at the very heart of the corpus, that is to say, virtually the entire artistic corpus from the 18th century onward.

There is a central question in academic research today, especially in critical race theory: hich archives should be analyzed when Black voices are either totally absent or only studied through the lens of the dominant narrative?

Therein lies the issue. First of all, and I think this is the easier option, we can look at memory as a phenomenon and turn it into an object of historical study. How has this memory been passed down? How has it managed to survive given the absence of documentation by those whom it concerns? On the other hand, there is currently a significant trend in US research that I, as an historian, have been reflecting on a lot. The idea is to compensate for the missing archives through developing a fictional project. I’m not totally comfortable with this approach because I believe that there is never truly “nothing” to be studied, and we should do everything we can to unearth what is there. By this I mean using all the historical rigor at our disposal to examine colonial archives and listen to the Black voices present in them, even indirectly. While not ruling out fiction entirely, which definitely presents its advantages, I nevertheless want to tread carefully and explore all that the colonial archives have yet to reveal to me.

Portrait of a Creole Woman in a Madras Tignon, attributed to George Catlin, oil on canvas, Virginia Museum of Fine Arts

You stated earlier that your last book involved a bulk study of the archives, but your residency in New Orleans actually led you to look specifically at the figure of Marie Laveau. Who was she and why was it important for you to delve into her history?

Marie Laveau was a New Orleans voodoo priestess who ran a popular divination practice. In 1819, she became wed to an emancipated Haitian immigrant named Gabriel Paris. I see her as belonging to a group of strong Black women from around the Atlantic characterized by their initiative, freedom, and business acumen, who excelled in spite of widespread colonial and imperial constraints. Marie Laveau was practically deified in her capacity as a priestess and, aside from her alleged supernatural powers, she was also endowed with great wisdom. Nowadays, she is as much a figure within the artistic landscape of Louisiana as she is within civil rights history. But in fact, no original portrait of Marie Laveau has ever been found. The only image of her is a copy of a late-19th-century painting attributed to the American artist, George Caitlin. As was my approach in my book on Toussaint-Louverture, I like to take on the challenge of studying both the portrait and the absence thereof. Such fluctuating histories—keeping in mind that Marie Laveau is now widely portrayed in popular imagery—reveal the importance of images in the act of memory. This point becomes all the more interesting when we consider how appropriations of Black history by diverse social groups coincided with the emergence of varied, often new types of knowledge. Allow me to explain. Earlier, I mentioned how Black history has been covered in the archives in a less conventional manner. This is because the majority of the written archives were not produced by the subjects themselves, in this case, enslaved people who were forbidden from learning to read and write. As such, we must proceed from a whole other angle to hear the Black voices in the colonial archives. But they can be heard if we listen…

In contemporary art, particularly among African-American artists, there is a desire to produce an alternate narrative and create a space for a Black perspective on history by reappropriating motifs from Western art traditions. The photography of Ayana Jackson or the portraits of Kehinde Wiley come to mind, among others. What is your take on this movement?

Firstly, I view it as a long and quite widespread tradition that has taken on a large variety of forms, dating right back to the Black British Art movement of the 80s. We might note, for example, the close dialogue that Yinka Shonibare initiated with the work of William Hogarth. I discovered Shonibare’s work at the 2006 Hogarth exhibition at the Louvre. His Diary of a Victorian Dandy (1998) comprises a five-photo series modeled after Hogarth’s series of eight engravings entitled The Rake’s Progress (1735). In this piece, the modern Shinobare was himself the main subject of a photographic epic mapped onto the narrative of his historical counterpart’s engravings. The result is a striking disjuncture placed within a familiar imagery.

African-American art offers some more famous examples, such as Kehinde Wiley, as you said, who has produced a number of remarkable paintings. At the Brooklyn Museum, I recently saw his painting inspired by David’s Bonaparte Crossing the Alps, which features a Black subject in the Emperor’s place. With this type of approach (which has actually become a bit too formulaic for my liking), he has achieved something fundamental: a way to evaluate Black artists within an art canon that was formerly believed to exclude them. Shifting the canon by making it Blacker is an effective method, as it allows the unfamiliar to be brought into the familiar; the lesser-known to be brought into the commonplace. And what we see from these artistic efforts is that otherness is not as far-reaching as we think. Which might suggest that in the world of art and culture, the operation to catch up on visibility has already been accomplished.

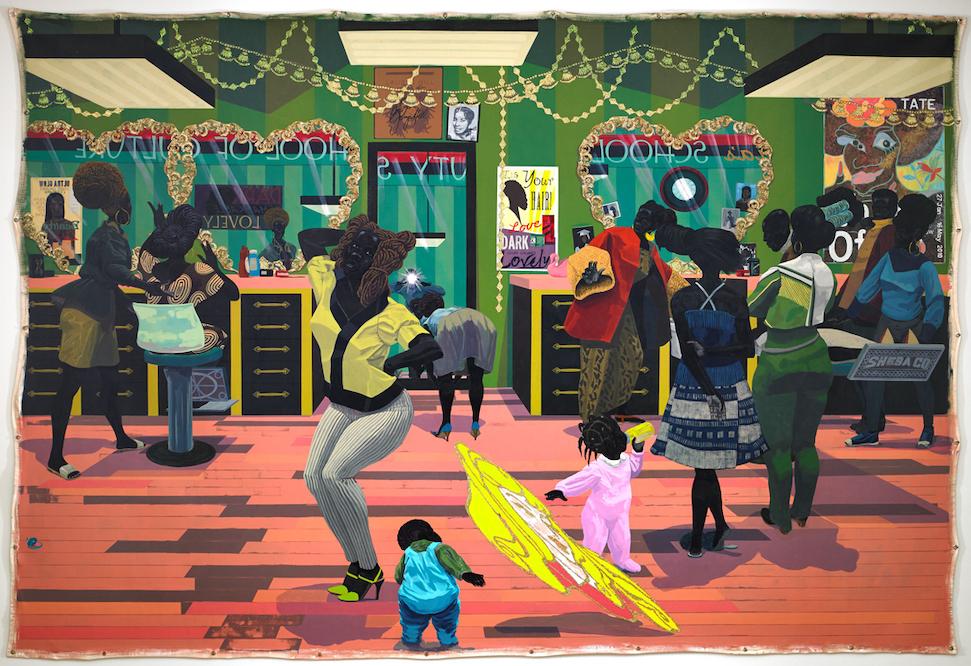

Kerry James Marshall, School of Beauty, School of Culture (2012), Birmingham Museum of Art

If the mission is already won, as you say, what’s next? What do you think would be the most interesting approach?

Perhaps we can now go beyond playing catchup, which has been a necessary step, but one that has eclipsed other finer artistic approaches to the African-American experience. For instance, we might consider a great artist who produced works all throughout the 20th century and even into the current one: Elizabeth Catlett. Working with a variety of media, including sculpture, engraving and painting, Catlett (1913-2012) brought her politically conscious art into the fight for civil rights, asserting the need for Black Americans to define their own means of artistic expression. She once said “we stopped thinking that we had to have straight hair,” a powerful statement that she believed should apply to media made by and for Black people. In its absolute terms, this sentence conjures up a compelling image, which becomes even more powerful when placed alongside one of her sculptures at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, entitled Woman Fixing Her Hair (1993).1

Kerry James Marshall embraced a similar approach in his magnificent painting, School of Beauty, School of Culture (2012, Birmingham Museum of Art). The work features references such as Holbein’s Ambassadors (1533, London, National Gallery), whose skewed perspective technique is applied to the figure of a young blonde girl. This anamorphosis appearing in the lower part of the painting is that of Disney’s Sleeping Beauty, here transposed into a Black hair salon. Hair is an important theme in the painting, touching upon the question of Black beauty standards. The anamorphosis, however, becomes a device to represent the misshapen, the misfit. The artist is mindful of Black beauty and culture as not necessarily being the antithesis of the “blonde” esthetic, but certainly as being detached from it. This norm has been cast into an incongruous shape, one that was perhaps a former obsession, but is now an ignored, inappropriate and ultimately ineffective model in this African-American school of beauty and culture. Kerry James Marshall plays with the artistic canon of the German Renaissance, setting it alongside motifs from pan-African culture.

For me, what’s so intriguing about this work is its subtle approach that speaks to the legitimacy, understanding, and culture applied to any action within the artistic domain. Visually, Marshall’s painting uses its own methods and imagination that go beyond merely quoting some antiquated European canon. It does not seek to introduce Black subjects into the artistic schemes of the French Old Regime, for instance. So, regarding your question of the most interesting approaches in Black art today, I would say that they lie in the artists’ capacity to transcend historical catchup and invent their own belated methods that more closely reflect African-American history and experience. And there are plenty of remarkable artists already taking this direction.

This article was originally published in States, A creative magazine by Villa Albertine available at the Albertine bookstore in New York.