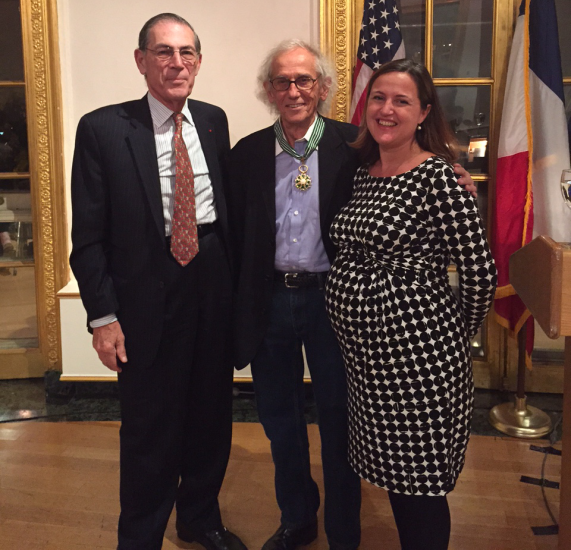

On Monday, November 2, 2015, Cultural Counselor Bénédicte de Montlaur honored renowned artist Christo with the medal of the Commandeur de l’Ordre des Arts et des Lettres. The award was presented in an intimate ceremony at the Cultural Services of the French Embassy in New York City.

Good evening! Thank you so much for being with us tonight. As Cultural Counselor of the French Embassy, I’m delighted to welcome you here as we honor the legendary artist, Christo.

Christo, you are known for creating some of the most important art projects of the last half-century, not to mention some of the largest. From “The Umbrellas” in Japan to “The Gates” in New York City, your works have attracted millions of visitors. Someone who has achieved such renown will inevitably be labeled with mischaracterizations and vague notions.

So, while you are very well-known, is it safe to say that you are not known very well? Let us try to know you a little better. To do so is to discover an even greater intelligence and creativity, for which France is honoring you tonight.

Even the name you have used to sign much of your art, “Christo,” does not reveal the entire story. For many years, “Christo” was in reference to both you and Jeanne-Claude, your partner in art, in business and in marriage. It was only later that your joint projects were attributed to “Christo and Jeanne-Claude.” So we must recognize that the honor presented to you tonight is owed to Jeanne-Claude as well. And while we wish that the late Jeanne-Claude could be here, you can imagine each time I say “you,” I’m saying the French vous, in reference to both halves of this remarkable duo.

You met in Paris in 1958. Christo was born in Bulgaria; Jeanne-Claude was born in Morocco. Christo was a refugee; Jeanne-Claude was the daughter of a two-star general in De Gaulle’s army. But by some remarkable twist of fate, you were born on the exact same day: June 13th, 1935. And your love story seems emblematic of your artistic career.

On one hand, it is a career that has crossed frontiers, passing from different countries and continents, even at a time when the world was starkly divided between East and West. On the other hand, it is a career forged on that perfect point of intersection, the symbiosis between you and Jeanne-Claude. It was your shared inspiration, your shared vision, and your shared commitment to your art that led to your iconic pieces.

Your installations are immediately striking, often overwhelming, even sublime. But on the surface, they reveal little of the complex process that led to their being. You venture all over the world to find the perfect landscape or building for each project. You drove for thousands of miles in the Rocky Mountains to find the ideal spot to hang 142,000 square feet of orange nylon polyamide. This was called “Valley Curtain,” realized in 1972. You roamed the deserts of the United Arab Emirates to discover the right location for “the Mastaba,” which has been in progress since 1977, and will be the largest statue in the world. You find artistic possibility in unnoticed corners of our environment – the curvature of a cliff, the outline of an island, the silhouette of a building.

Determination and patience drives your work. You are undaunted by even the most massive projects, whether it’s miles along the Arkansas river, or a million square feet on the Sydney coast. You are undeterred by difficult geography or inclement weather. And perhaps most impressively, you are not afraid of bureaucracy! Your installations often entail many layers of public approval, and red tape at every stage of the journey. But I never met artists who were so adept at handling government agencies!

You sometimes wait decades for your plans to be realized. In 1971, you decided you wanted to wrap the Reichstag in Berlin in fabric. If the physical process sounds challenging, the process of gaining approval was even more so. You spent years visiting hundreds of German parliamentarians, to convince them of the common good of your idea. You persevered against biases stemming from Germany’s East-West divide. And finally, a vote was held in 1994, resulting in a narrow victory in favor of your project.

There have been a few times when bureaucracy has stubbornly stood in your way, and your projects were never realized. Your request to wrap the statue of Christopher Columbus in Barcelona was denied twice. When permission was finally given in 1984, nine years after your first request, you decided it was better to move on to other things. But even these unrealized projects exist through sketches, models, and in our shared imagination of what might have been or could still be.

And so, the bureaucracy and opposition became inextricably linked to the art. The realized Wrapped Reichstag spurred a flurry of opinions, some positive, and some negative. The level of human engagement behind your piece was as striking as the piece itself.

You may have to involve governments for their permission, but you are never indebted to them. You self-fund your work, relying on sales of your statues and sketches. You reject the artistic compromises that can come through government involvement and developed a way to realize your artistic vision with a minimum of outside interference.

Your projects have brought avant-garde art to a wide public, attracting far more than just art specialists. All of New York City remembers The Gates, your 2005 installation of more than 7,000 vinyl gates in Central Park. I hear that, at the time of your installation, all of New York was a buzz. Your work was a success on all sides: among critics, art historians and the general public. And of course, the bright orange fabric panels injected some much-needed color into dreary February in New York. You gave the park a festival-like aura, where someone’s morning run felt like part of a sacred procession. You drew out millions in crowds at a time of the year when most people prefer to stay in their homes. You defy habits and routines and open up new possibilities amidst the routines of everyday life.

When you wrapped the Pont Neuf in Paris in sand-colored fabric, you erased the bridge’s famed ornamentation, and reduced it to positive and negative space. So the public now saw the bridge purely in terms of shape. And you made us to ask ourselves, is the Pont Neuf still the Pont Neuf without those decorative sculptures? What is it that turns a bridge into a national icon?

And what we’ve all discovered through your work is that temporary installations can have very lasting effects. Even today, people will still talk about The Gates in New York, or the Wrapped Pont Neuf in Paris. And when they talk about it, they talk about more than just the work itself. They’re reminded of what their lives were like at that particular point in time. They reflect, and they reminisce. As your pieces prove again and again, powerful works of art create an anchor in our memories, an essential point of reference. Jeanne-Claude once said she thought the best things in life were temporary. Your installations make us agree with her.

For all you have achieved, France is honored to have been a part of your career, and not just as the site of the Wrapped Pont Neuf, but also as the source of your inspiration and your artistic beginnings. When you left Bulgaria, you weren’t sure what direction your art would take, or what medium you would use. When you moved to Paris, you met Pierre Restany,a leading figure of nouveau realisme, which ran in parallel to the Pop Art movement in the United States. And nouveau realisme helped you develop your understanding of art as something that incorporates the everyday and makes it art.

The legacy of Dadaism and Marcel Duchamp in nouveau realism encouraged your fascination with objects. And you were a part of their early experiments in moving art out of the gallery and into the street. But you sampled from nouveau realisme and gave it something new. You began wrapping objects with fabric, notably chairs, but you would leave a little piece of the furniture sticking out. Moving from the iconography of pop culture to something more abstract, and more mysterious. Art critic David Bourdon would later call your wrapped pieces “revelation through concealment.” You fostered your artistic style in France, moving from wrapping furniture to one day wrapping landscapes.

Most importantly, Paris was where you met the love of your life, Jeanne-Claude. And France became the springboard for your artistic career. Your first collaborative piece, entitled “Dockside Packages,” was set up in Cologne harbor in 1961. The stacked oil barrels covered in fabric sparked much intrigue and confusion among the Cologne inhabitants. And it also sparked a lifetime of joint work between you and Jeanne-Claude. One year later, you set up the “Iron Curtain” wall of oil barrels in Paris, blocking the Rue Visconti. And while the police only allowed your installation to stay in place for a few hours, the piece gave you an international reputation that has held up to this day.

Christo, it’s not only your artwork that is astounding. The unique story and process behind your work is an inspiration to us all. You and Jeanne-Claude made a life’s mission out of enriching the public experience of art, and for that it’s not just France that is grateful, but the entire world as well.

Christo, au nom du gouvernment francais, je vous fais Commandeur de l’Ordre des Arts et Lettres.