LOVE ME TENDERLOIN

In this text, science fiction author Alain Damasio reveals the hidden face of the city of San Francisco. Inspired by the investigation he carried out during his residency at the Villa Albertine, this story reveals the perverse effects of modernity and capitalism on human beings.

It’s an asylum without walls, open to the sky. Needless walls.

For these souls already carry their own walls within themselves/intimate and caved in.

In Tenderloin, San Francisco’s poorest neighborhood, two blocks from Twitter’s headquarters, rubbing elbows with the most brutal wealth, madness is everywhere—liquid, tranquil, viscous; it flows through the streets and roams the plazas. It congeals further up, at the edges of sidewalks, on a garbage or a bench—rises and sets off again. Madness is fascinating when it is “free,” as it is here: it takes on every shape, every body, it inhabits them and it breaks them, it batters them like a gong, still standing, tottering, until it lays them out on the asphalt as upon a mattress.

No more filter, no more screen. No more interface, no more anything: the real.

You walk six feet from a handicapped man who digs with his right foot to pull forward his wheelchair chariot, sagging under three backpacks. An old lady with features as wrinkled as an apple takes a punch; her face absorbs it, except there’s no punch, and no more face, just this fear that opens her eyes wide. Cyclically.

Anything could happen and nothing happens. Not today. Or rather, so many things, so many events of banal horror that it ends up not mattering anymore.

Circling a garbage can, a shirtless hooligan, muscles tense, fends off an eternal assault. An adolescent, white as an Irishman, dropkicked to the ground at a bizarre angle, reddens in the sun, ten feet from a half-dressed couple stuck in a one-person tent. Two guys heat crack in the hollow of a sheet of tin foil, as if camping on the fly.

©Yann Legendre

“The number of people here who are thinking alone, singing alone, eating and talking alone in the streets is alarming. Yet they don’t add up to anything. On the contrary, they subtract from one another, and their resemblance is uncertain,” Baudrillard was already saying in 1986. That’s exactly it: all stuck in the same shit, but in a way so fiercely lonely and incomparable that they form no group at all, no shared situation. Each person confronts the whole of wretchedness on their own.

Ronald Reagan found psychiatric hospitals “awful,” so much so that he closed them in the 1980s. Quite simply. Why bother? Since then, the streets of the poor neighborhoods are a psych ward left to its own devices that nobody is able to manage or fix anymore. Yet the city spends 80,000 dollars per homeless person per year, my contacts here tell me, with little success. The liberal (leftwing, according to the American classification) reputation of the city has made it a magnet for vagrants, a problem amplified even more by two years of covid.

In France, we have people without homes, of course. Here, we’re a step beyond, not only because they are far more numerous and haunt the city center, but especially because they are much more affected and ruined.

From what I’ve gathered, social services dedicated to the homeless don’t exist in the city. San Francisco finances external associations to try to manage this misery. Which naturally opens the door to frequent corruption—the concurrence of enormous sums available for institutions independent from city hall, whose effectiveness is very hard to measure.

During my “visit,” a little herd of yellow vests is at work, marked Urban Alchemy, with a logo that blends into a single strange graphic the Illuminati, the Freemasons, and New Age aesthetics. They are widely deployed in the streets we wander.

In France, this would be called an NGO. Here they are called a Non-Profit Organization—and the very fact of defining a social, cultural, or humanitarian association according to the negation of profit crystallizes, to my mind, an American vision. The norm is profit. It’s the axis around which the true stakes turn. Everything else is defined in contrast to this. Exactly like essays and thinking are nonfiction. Philosophy, sociology, hard sciences, ethnology? Nonfiction. Is that to say that in the realm of books, fiction is the norm?

In the street, the devil is in syringes and powder: the infamous fentanyl, unknown in France, fifty times more powerful than heroin and infinitely less expensive. Two milligrams are enough to trigger an overdose; it can be cut with whatever you like, put it in aspirine pills, add it to coke, to junk.

In San Francisco, overdoses killed more people than covid in 2020: 700 dead, recalls a subway poster. And it’s rather better that way, right? Poverty self-regulates, self-negates; fentanyl does the job of social services, of the government—and of capitalism, absolutely and totally irresponsible, resigned, and sickening.

There are 78 billionnaires in Silicon Valley, right nearby. Around 20 million dollars in wealth, you’ve got yourself a house and a really nice car, a financial director here told me. With 200 million dollars, you’ve got a jet and you take your long weekends off in Burgundy. When you come back, you arrive late to the board because you have to make a pitstop and fill your plane with kerosene.

1% of the wealth of a single one of these billionaires would no doubt suffice to treat these people, at least to protect them from others and from themselves. To pay for long-term social action worthy of the name, to build a shelter for them and to provide salaries for psychiatrists and nurses who could care for them.

It won’t happen. Tenderloin stagnates in its shit, in its death; you walk on turds that are not those of dogs.

Why? Why in the world? How can the most obscene wealth stand right up against, be practically stuck, to the fiercest poverty? How can this be accepted, by me first of all? How can revolt or revolution not knock all this down—with an insurrection? How can the Twitter building stay standing six hundred feet from here and not collapse beneath an attack of drugged zombies at last aware of what would happen?

The answer, it seems to mem, is not complex. It is not simple either: it is profound.

The art of detachment

I am going to try to propose a hypothesis. It is partial in both senses of the word.

It does not bring up the Puritanical ethics that consider success and riches proof of divine election and poverty, implicitly, as deserved by those who live in it, or at least as a bad sign. It does not discuss the values of the European left neglected by counter-culture, which is to say equality, in favor of an individual liberation made into the number one priority, a state of affairs which explains in part that such staggering inequalities are more tolerated in the USA than elsewhere.

I have no solution, nor any visionary power. I just don’t want to tell myself it’s normal, and move on to other things. Millions of people can be seen to show affection for their pets, without the realization that the animals that humans in the streets also are, would deserve an just as much attention.

©Yann Legendre

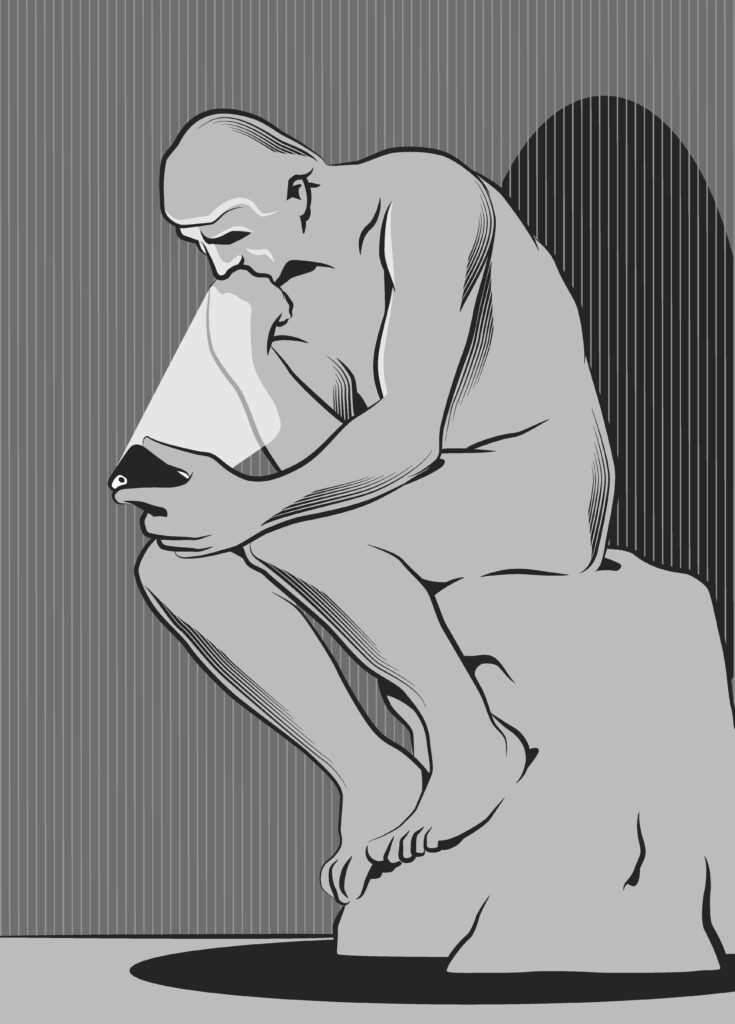

The hypothesis is as follows. What is missing, according to me, at both ends of the spectrum, from the wheelchair-bound psychotic up to Mark Zuckerberg, and the 22-year-olds with 15,000 dollars a month salaries along the way, and you and me as well, who don’t do any heavier lifting than, at best, feeling indignant as we gently caress the screens of our smartphones; what’s missing is ties. Minimal empathy. The lofty human faculty, but also the fully animal faculty, to be able to suffer and feel along with. The faculty to be traversed by that distress, to receive it in us, to the point of not being able to tolerate it any longer without acting.

What’s missing is an aptitude, now largely lost, lying fallow or left overgrown by our digital modes of life, for confronting alterity. That which is not us, that which we have not lived through, do not share directly.

This faculty of projection, this capacity for existential listening or welcoming of what is outside of our bubbles, this ability to move out of ourselves, or even without leaving oneself behind, to open oneself up for others to enter into us, come and affect us, impact us and shake us up, this faculty is the first thing that the digital world has degraded as it has extended its reign and its practices over our existences.

And that is perhaps the heart of my technocritique. Such as it has been developed, “democratized” Tech is first of all a social machine for amplifying ego-centers and for making them its centers of profit. Consequently, for recreating connection by way of intermediary interfaces that cut bodies off from all sharing (since a “virtual” connection produces information ceaselessly, hence exploitable traces, thus profit, which IRL ties don’t produce).

It can’t be highlighted enough: social media connects us, but does not tie us to one another. It assembles us, certainly, without ever obtaining us togetherness. In an elegant gathering, together they articulate the scattered grapeseeds we have become and make of us suspended clusters, online communities, networks of complicity or affinity, yes. But they always unite us as separate. They unite us in physical distance, they space us out while putting us in touch, they banish all carnal or corporeal dimension, all incarnate presence in favor of videoconferences, images, and messages; in short, in favor of King Information that will reconstitute these in bits and pixels.

Where is touch in a force-feedback glove? Where is the scent of skin? Where is the sensation of a body, the heat of a hand taking my own or being placed on my shoulder? Where are the kisses, where is the taste of a fruit, a cheese, the flavor of a wine?

The most hyped modernity is associated with the quality of simulation. Without seeing that this fascination for the simulated, for reality reinvented by dint of teraoctets processed in real time, has something naive and illusory about it, the dream of a nerd or geek, which to my mind oozes has-been while disguising itself in the accoutrements of should-be; that is, of a sexy future. Reinventing one’s relation to the living seems so much more modern to me, in fact.

It’s no miracle that the moguls of Silicon Valley have made a world in their image: the world of meat, of body = meat, of mind = computer, nothing else, and they have marketed this to us throughout the world. A mode of timid eternal adolescents, incapable of relating directly and fully to others and who elude this separation through networks. Nick Pinston, who knows the founders of Facebook personally, told me his vision of them: they are all autistic, people for whom it is just… difficult to have normal social relationships. Social networks were born of their quest for a technology that might resolve this after their fashion. In tune with their fear of the other and their desire for exchange, in spite of everything. And they fix it.

Tenderloin is beside the Financial District. No fence, no wall, no separation puts distance between them. It’s just that the separation is the glass of our screens, the walls of our filtering bubbles.

GAFAM hasn’t killed our ties, has not cut them with a knife or an axe. It’s worse, more effective and more subtle than that, and above all, it wasn’t explicitly conceived of or intended to be that way. It sounds more like the collateral damage of a guerre that didn’t even happen. They devitalized those ties. They edulcorated them, disintensified them. They gave us the daily means, through their platforms and their applications, to become perfect, self-satisfying in-dividuals, or lived as such, desiring to be such—that is, human beings who are no longer divisible, no longer share with others, do not offer a single piece of what they are to others who might need it.

Or, when they do so, they do it at a respectable distance, in tolerable social distancing, without committing themselves, without putting themselves in danger in any way. This mental and physical security was latent, no doubt, in negative human vital impulses, it was waiting, as if in the shadows or on the flipside of the desire for encounter and confrontation that also evolved to constitute us, and that was activated because it was also and perhaps especially the best way to survive.

Today, once a certain level of comfort is attained, this confrontation no longer needs to take place. So we live in the null location of communication and exchange, in the non-presence of platforms that replace experience or absorb it as soon as it blossoms. Instagram is a blotter that drinks up the fugitive intensity of our ostensibly rich moments.

Without ties, anything becomes possible. The extremely rich can live beside the wasted homeless and remain unmoved. It’s not even a question of morality anymore, it’s a question of the anthropology of relation or of human rapport, that has been lost. Tenderloin is seen, known, accepted. Because for us, as for the Terminator: “the data would be called ‘pain’.” I mean: their pain, for us, is just a piece of information. It is transmitted to the cortex but is not felt.

Silicon Valley offers us an American world, regardless of what we think of it. Nothing universal, in truth. It promulgates a relational culture that never takes as its point of departure a collectivity or a community, as in Asia or Africa, to take some rough examples, only from the individual as atom and center of its world, for which possible relationships with others must be thought after the fact.

Windows Into The Tenderloin

Lisa Ruth, my guide, a talented historian, a grassroots activist as well, leads me before a magnificent mural at the corner of Golden Gate Avenue and Jones Street.

It’s a work by the artist Mona Caron, deeply moving in its simple beauty and by the implication of citydwellers in its elaboration.

The work is a triptych whose first panel represents what is now the neighborhood’s past, such as it was when it was painted: a “parking lot.” The second is the neighborhood going about its business, except that each character figured there is a real person that Mona painted and integrated into her mural. A sign indicates “one way.” The last panel is the most beautiful, reddish tones and green; it is adorned with the sign “another way” and translated what the neighborhood could become in the future if one followed another path, without gentrification and without urban planning descended from on high: just through the action of citydwellers and on the basis of realizable goals.

This third panel, as Mona explains on her website, has become a means for the community to envision an alternative future, another way for their community to exist.

©Yann Legendre

The whole thing is called Windows Into The Tenderloin.

Mona Caron explains: “The window showing “Another Way” is again populated with the neighborhood’s people, some of them doing a specific activity they’d wished for, others simply sharing space in a convivial way with people of different local communities and identities. […] The inclusion of local people in the future-fantasy panel was particularly crucial to the concept of this mural, because I strived to conjure up a vision for a more uplifting, convivial and beautiful environment in this neighborhood without a change in population, which is improvement without gentrification.”

“I tried to let this utopian painting “grow from below”—through a loose and casual participatory process […]. By then, I’d found out about many people’s talents, or their hopes and aspirations, or learned about the work they do besides their job that they derive more meaning from…”

Mona also asked the inhabitants to make suggestions to her: what would they like to see here, if it were up to them alone?

« Slowly, an alternative vision of the neighborhood emerged. I built upon my own ongoing series of “utopian” visions of San Francisco while integrating the ideas that emerged from these conversations with passersby, which ranged widely from the pragmatic to the fun and silly… For the changes to buildings and larger infrastructure, I tried to pick ideas that could conceivably be implemented and maintained by people themselves, without massive top-down intervention. I also prioritized re-purposing things that are already there.”

The mural is magnificent, honestly. You can sense a profound generosity that no doubt stems from the way it was created, woven at the level of the neighborhood and its inhabitants. A little fish farming basin is there, common gardens, a bookstore, give-away shops, a gift economy, a poet being listened to, a community-oriented way of life, housing affordable to all, people dancing on a patio, looking at each other and talking to one another, eating or playing together, green roofs,

All this comes from the people’s heart, from their dreams; the graphic design just spatialized these and set the scene. But it forms a very moving image of a possible future: another way.

A few awful tags have dirtied the mural a little, the paint is flaking and falling off in places, which upsets Lisa, who you can tell is very attached to this work and this process. But it’s there and it holds up the walls, more than the other way around.

Mona Caron didn’t do anything fundamentally extraordinary: she just stayed there, slowing painting, conversing, talking to passersby, listening to them. She took the time. And she metabolized not just the neighborhood as it was, as it is, but the neighborhood as it dreams itself and as it could be, bringing this latent imaginary out in her colors and her lines.

This utopia is credible, intelligent and articulated. It doesn’t have the improbable character that utopias sometimes have; quite the contrary: it is quite exactly the alternative path that this world and these neighborhoods could take, if they were protected from drugs, deals, corruption, and if a negligible percentage of the riches produced just next door in the bay area were provided to realize what the inhabitants themselves would wish to build or develop. It would really only require leaving it up to them and giving them the resources.

Further along on another corner, market bins have gained ground against parking spots. It’s a small thing, but it helps.

Love me tender, love me true is stuck in my head since this morning.

I mentally project the mural in my head once again.

What strikes me is that there aren’t immense SUVs on it, pretentious skyscrapers, theme parks or flying cars. The only flying thing is a hot air balloon and some birds. As it the tech utopia no longer inspired these neighborhoods, or as if they instinctively knew that for them, it would bring nothing.

What they dream of is very simple and very complicated to bring to fruition here: they are dreaming of a life of togetherness. They are dreaming of something called friendship, called love, called attachment to others, shared and reciprocal.

Love me tender, love me sweet,

Love me tender, love me true

All my dreams fulfilled

Love me tender, love me ten-der-loin !

Translated from the French by Alexander Dickow

llustrations by Yann Legendre

This article was written by Alain Damasio on April 28, 2022 and appeared in the first edition of States magazine, before the publication April 12th of Alain Damasio’s book “Vallée du Silicium” (Albertine/Seuil) in France.